I want to start with an affirmation: Conspiracy Theories never truly die; instead, they always come back in new forms. A good example of this maxim is a conspiracy theory that has gained some popularity lately here in Brazil – the NESARA or GESARA conspiracy.

The name relates to an economic plan introduced by Harvey Francis Barnard in the 1990s – he distributed his proposals as the National Economic Security and Recovery Act, or NESARA. He claimed that the US economy’s main problem was debt, and so the solution would be to remove compound interest on loans and return the economy to a bimetallic system. As the proposal never reached congress or any authority, Harvey released it to the public domain and created an institution called NESARA, in 2001.

Those are the historic and factual bases of NESARA, which rarely appear in the version popularised by conspiracy theorists. Instead, the narrative that gained traction is the one put forward by the “Dove of Oneness” – whose real name is Shaini Candace Goodwin. Goodwin could be the subject of an article in her own right, as she has an extensive and very interesting history, but what is relevant here is what she said about NESARA, as it became the basis for this conspiracy theory.

Goodwin claims that the NESARA bill actually did make it to congress, where it was approved during a secret meeting and signed by President Clinton (something which would be later contested by other conspiracy theorists). She believed NESARA, when put into action, would force all the banks around the world to pay people back the money they ‘stole’ via interest and charges, along with rendering taxes illegal, instituting world peace and forcing new elections in the US for president and for congress.

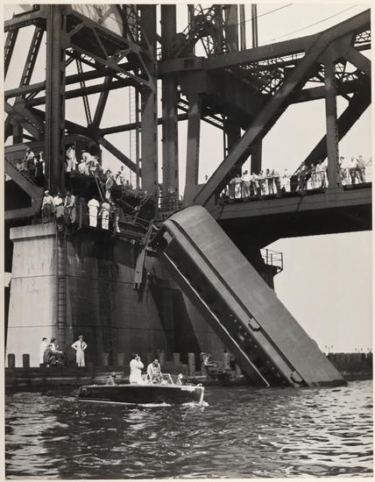

According to the conspiracy theorists, the plan was supposed to be enacted at 10am on September 11th, 2001, and it was due to take place at the World Trade Centre because of its importance on the global monetary system. As the theory goes, 9/11 was actually an attempt by the shadow government to stop NESARA from being enacted, so as to ensure that banks around the world would not collapse. Goodwin claims those shadowy forces silenced anyone from ever talking about this, but that there are brave souls – called the White Knights – who fight against the Deep State to reveal the truth.

This conspiracy theory continued to grow and change through the 2000s, taking on new forms and new variations, but the change I most want to focus on occurred since 2016. These days, the theory goes by the name GESARA, and the history has shifted somewhat: its origins with Barnand have been completely removed, and instead, in its modern form, the creation of the plan is attributed to Donald Trump.

What is interesting is the plan has been elevated from a national level to an international plan: it is now called the Global Economic Security and Recovery Act (GESARA), and modern versions of the story claim it was actually the UN who held a secret meeting and approved this plan, which was supposed to be acted on 9/11 of 2001 – because the plan was so good that the entire world wanted to be in on it.

In the new version of the theory, Clinton actually tried to stop the evil plan, but congress forced him to sign it. Other versions of the theory claim that Trump secretly signed the enforcement of GESARA, as part of the Paris Agreement, or the Peace Deals with North Korea, or any other time where he has signed an agreement.

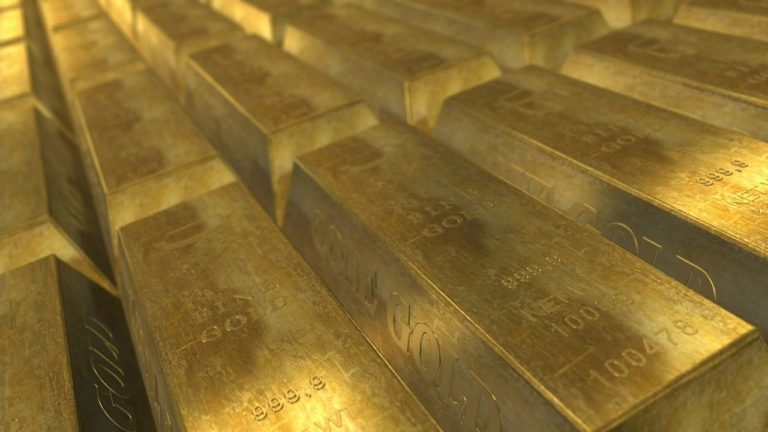

Most recently, a range of embellishments have been added, including that the enactment of GESARA will involve the release of thousands of secret patents for medications and treatments. The original theory claimed that the new economic system would be based in metallic reserves; the more popular narrative these days is that money will return to the gold standard. The secret cabal at the heart of the plan now extends beyond the banks, and involves President George Bush, the Illuminati and the ‘Globalists’, and so on. The development that the Clintons were trying to stop this plan at any costs is an interesting reversal of the original versions of the conspiracy, which blamed the Clintons. It is a particularly interesting addition, given how hated the Clinton family is in conspiracy theory circles.

The NESARA/GESARA theory is an illustration of how conspiracy theories do not die, they only shift and are reborn. In this case, the fear of banks and the Federal Reserve is an old fear, it predates the creation of either in the US, so the theory has some deep roots to draw on. It also feeds into fears about the collapse of the value of money, and the trope that “Taxation is Theft” – the belief that any type of control or tax of the government is unjust. NESARA is simply the rebranding of narratives that claim to solve these fears and questions, by linking the value of money to something tangible, and to reassure people that while banks have been evil and dishonest, things will be fine once they can be forced to give the people their money back.

These fears, today, are global, which is why we’ve seen the ‘NESARA’ conspiracy become ‘GESARA’: the same narrative can be used all around the globe, not just in the US. Indeed, the first time I ever heard about GESARA was in Brazilian conspiracy theories.

With COVID-19 and the related economic crisis causing global anxieties, it is perhaps no surprise that the GESARA theory emphasises the release of secret patents – for treatments that will cure the virus and heal the world, bringing an end to the economic uncertainty.

It is almost as if the conspiracy theory is the antagonist in a slasher or horror movie: it never dies, it always finds a way to return, perhaps dressed a little differently or with a new gimmick, but always following the original pattern. And just when we think it’s defeated, someone or something will disturb it’s grave, and it will return to haunt everyone again.