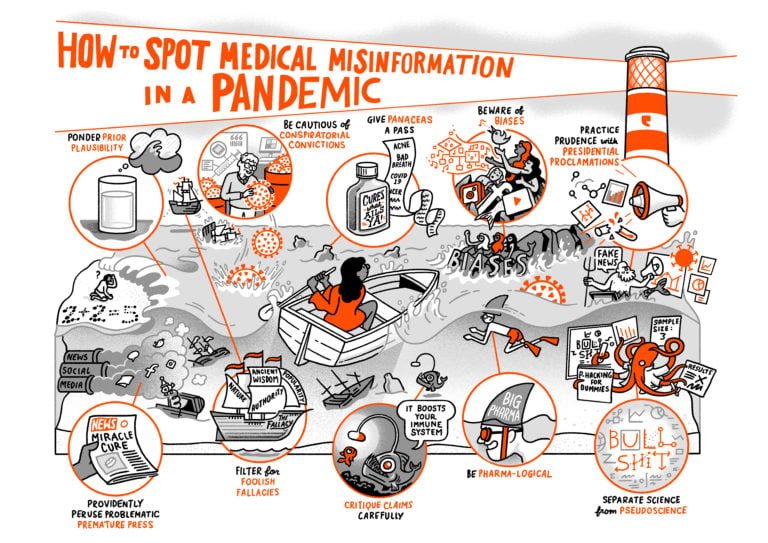

I wish I could open the new year with an optimistic article, but that’s just not where things sit at the start of 2021. The removal of Trump, whatever muddling through post-Brexit option is currently gaining traction, these are not signs we’ve turned a corner. They’re ventilators in a pandemic where we’ve yet to find a vaccine. The most dangerous public health risk of our time is epistemic in nature, it’s the virality of misinformation that continues to run rampant across poorly managed media.

There’s a deep irony to our epistemic crisis: we live at the peak of accessible knowledge, yet there’s so much anxiety about our ability to justify our beliefs. There’s no single cause for this epistemic crisis; it’s a perfect storm of society, psychology, and technology. Rapid social change brought about by technological and political upheaval lead to substantial polarisation, then the internet flooded our lives with the culture war and made everyone compulsive participants. Now social media entities have weaponised cultural conflict on a scale that would make Goebbels do a full Grinch smile.

Recognising that every crisis is also an opportunity, enterprising individuals have entered this dysfunctional marketplace of ideas and set up shop with a variety of pernicious wares. Skeptics are likely to already be familiar with the sorts of overt conspiracy theorising and woo that are running rampant in the poorly regulated corners of the internet, so I want to focus on a problem that’s endemic to the skeptic community: the rise of cheap talk skepticism.

We’re all intuitively familiar with the idea of “cheap talk”, but I want to make explicit the key features and how they manifest in some acts of superficial skepticism. ‘Cheap talk’ refers to talk where the person doing the talking is at little to no risk of suffering any serious consequences for their comments. Cheap talk is at the heart of such beloved internet personalities as virtue signalers, keyboard warriors, and sea-lions (as my good friend C. Thi pointed out). The last group are closest to my concern around cheap talk skepticism.

Cheap talk skepticism occurs when someone expresses skepticism in a way that comes at little cost to them, though it frequently comes at a significant cost to others. For example, if I express glib doubt about the personhood of another group of sentient beings, when my personhood is highly unlikely to be questioned, that would be cheap talk skepticism. Furthermore, if I received praise and positive reinforcement for my skeptical signaling, we could see that skepticism as effectively free of cost.

Skepticism, both as a broad perspective and with regard to specific issues, has traditionally come at substantial personal cost. Humans are generally a credulous species, our belief formation consisting of a mixed bag of heuristics with the thinnest veneer of rationality. That allows for quick and decisive belief formation, but it also arguably creates a hardwired animosity towards skeptics. Skeptics are seen as risking social instability with their skepticism about deeply held community beliefs. So, it’s no surprise that skepticism about things like the existence of god still comes with substantial social costs in supposedly secular nations, and the death penalty in others. For many, skeptics are most charitably seen as busy bodies who should really stay quiet during family meals.

In the age of the internet though, there’s an audience for mass produced skepticism, and the cost for producing that skepticism has dropped to almost nothing. At first glance, that could seem like a good thing. One might argue that the goal of Mill style liberalism, the sort that’s highly valued by free speech advocates, is to create a space where speech in general comes with little to no cost, since that will promote the greatest free exchange of ideas. While I sympathise with this principle in theory, the unfortunate reality is that talk is rarely free – it’s more a question of how much the cost is externalised or carried by the speaker. I’ve discussed before how radically unmoderated speech comes with substantial costs, but it’s not hard to understand how completely unfettered cheap talk skepticism could quickly spiral into dangerous conspiracies. The same rising distrust of institutions that is making space for more secularism is also making space for more anti-vaxxers, more Q-anoners, and as always more anti-Semites.

Cheap talk skepticism feeds on all the situational factors I’ve mentioned. It’s understandable that many people would respond to the overwhelming deluge of the information age by craving the skeptical freedom of suspending judgment. There is an undeniable joy in saying “I don’t know and neither do you, leave me alone” in response to the constant demands for verification that we all face. As Marsh recently wrote, we need a sympathetic approach to the way that human psychology makes us all vulnerable to cheap talk skepticism. We’re all drowning in a sea of information, it’s hard to judge people for grabbing any skeptical life preserver that comes along, even if it turns out to be attached to conspiracy theories.

If there is any room for criticism in this explosion of cheap talk skepticism, I believe it should be focused on the individuals with the platforms that allow them both the time for proper skepticism and the obligation to skepticism properly. In the parts of the skeptical world referred to as the Intellectual Dark Web, there has been rampant cheap talk skepticism around both Covid and the recent American election. Under the umbrella of “distrusting institutions”, there has been such an absurd amount of “just asking questions” that Sam Harris felt compelled to very publicly “turn in his IDW membership card”. Unfortunately, Harris neglected to explicitly criticise anyone by name, which makes is hard to determine if his criticism was meant just for the brothers Weinstein, or if he was including folks like Maajid Nawaz, who he has frequently promoted and who I’d argue has been one of the worst of the cheap talk skeptics.

For example, here’s Nawaz retweeting Team Trump Twitter sharing a video from OAN (One America News Network), an unreliable right wing “news” organization, which they claim is evidence of election tampering. Rather than emphasise the high likelihood that the video proves nothing of the sort, Maajid’s response is “I see what this looks like & I hope I’m wrong” followed by “sensible people should agree that this entire controversy needs to be resolved ASAP & urgently”. That tweet is not an isolated event either, here he is unknowingly sharing election fraud conspiracy materials from the explicitly antisemitic Red Elephants website. Here he is getting strung along by Trump’s reality tv shtick . Here he is citing Ted Cruz’s election denialism as proof that Nawaz was “right all along”. I could continue, but the pattern is obvious, and it’s not unique to Nawaz. This is deeply irresponsible, but the cost of cheap talk skepticism will be born by the American electorate and not by Nawaz, who has since circled back around to claim the OAN video produced a state audit, but not to point out that Georgia found no significant fraud of the sort that Team Trump and OAN were claiming.

Nawaz has also engaged in cheap talk skepticism around Covid conspiracy theories, favorably retweeting a thread by a guy who thinks Covid is caused by 5G and directly quoting his claim about “the myth of a pandemic”. Similar cheap talk skepticism towards Covid and the Covid vaccine has arisen from Brett Weinstein and unsurprisingly from James Lindsay, given his ongoing business relationship with conspiracy theorist Michael O’Fallon. James recently attended a Sovereign Nation conference and a conservative event in California with Covid lockdown skeptic Dave Rubin. Rubin has attended several anti-lockdown events and posted cancel bait tweets implying that he’s hosting dinner parties in violation of social distancing rules. Again, the cost of their skepticism is far less likely to be born by them than by medical workers and vulnerable individuals, like my aunt Sue who suffered a stroke while being treated for Covid. Society doesn’t even condone the desire that they should directly experience the consequences of their skepticism. We’re forced to hope that their cheap talk remains cheap.

Quality skepticism is research intensive. It’s not easy to do quality skepticism and still produce hot takes across a wide range of topics… Properly justified belief lags behind misinformation in the best of times. Cheap talk skepticism widens that gap by forcing skeptics to correct this internal misinformation alongside all the other forms of cheap talk.

Besides putting lives at risk by promoting a cavalier approach to a global health crisis, cheap talk skepticism externalises a social cost by driving quality skepticism out of the marketplace of ideas. Quality skepticism is research intensive. It’s not easy to do quality skepticism and still produce hot takes across a wide range of topics, which is something that public intellectuals are unfortunately pressured to do in order to stay relevant. Properly justified belief lags behind misinformation in the best of times. Cheap talk skepticism widens that gap by forcing skeptics to correct this sort of internal misinformation alongside all the other forms of cheap talk out there.

So, how do we tell between cheap talk skepticism and the real thing? As usual, it’s not easy. When you’re engaging with a skeptics’ argument, we somehow have to include questions like: Does the skeptic genuinely have skin in the game, even if it’s just in terms of reputation? Does the skeptic circle back around and update their skepticism on the subject? Do they make explicit the potential costs of their skepticism and discuss ways to avoid externalising that cost? Is their framing catastrophising or contextualising?

These are hard questions, which is why I’m not especially optimistic that we’ve seen the peak of cheap talk skepticism. We’re all epistemically exhausted and the crisis is just coming to a middle. That said, if 2021 turns out to be an epistemic bonanza, I promise to come back and eat my skeptical words.