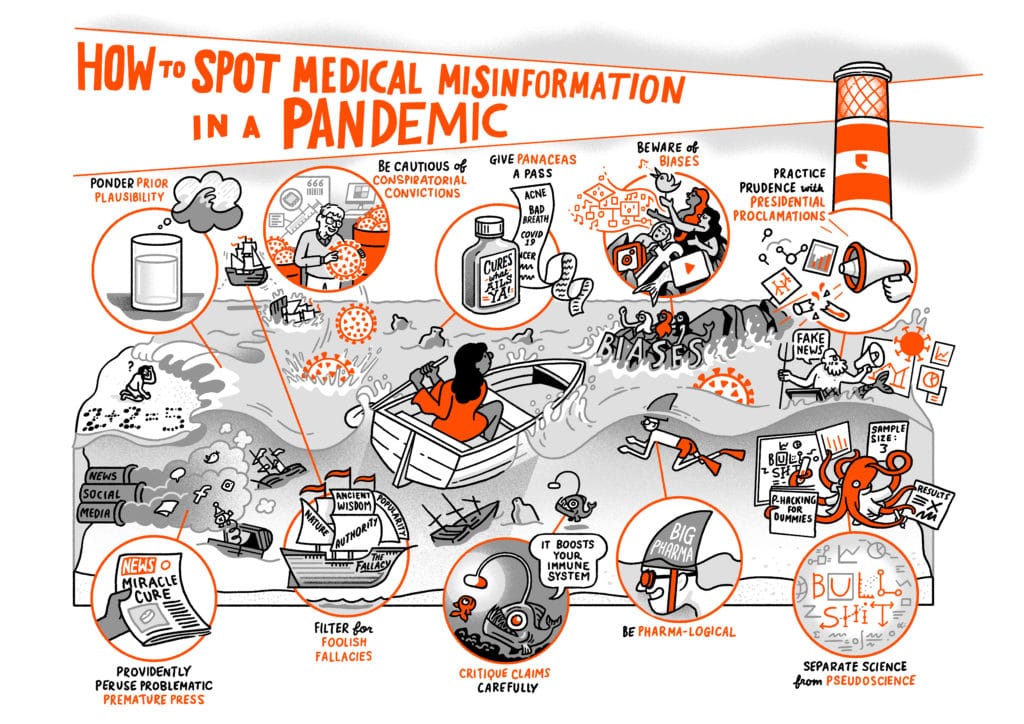

The internet has revolutionized society in ways that could scarcely have been imagined just a few decades ago. There’s a vast ocean of information to dive into and explore – and it’s only a click away. Unfortunately, that ocean is badly polluted, and the sewage continues to pour in.

It therefore puts us in a difficult position when it comes to figuring out what we should believe, and how that informs our actions, particularly when it comes to matters of health.

That polluted ocean is populated with a plethora of predators, and some well-meaning but hopelessly deluded parasites. They’re all hoping you’ll eschew ‘mainstream medicine’ and invest your faith, and money, in their products.

The good news is that there’s nothing new about the selling of snake-oil, and the warning signs can be relatively easily spotted in most cases. The bad news is that we’re in the middle of a global pandemic, so we’re scared, we’re grieving, and we’re desperate. Add to that some information overload and we have a perfect cocktail of confusion to lead you to making bad decisions.

As a remedy, we prescribe a healthy dose of (scientific) skepticism and critical thinking skills. To help you on your way, here’s our top-ten tips for spotting questionable health claims:

1: Ponder prior plausibility

When it comes to any proposed medical intervention there should be some form of mechanism in action. Evaluating the likelihood of that mechanism against what we know about how the world works can be telling. Homeopathy, for example, relies on a method of repeated dilution of an (alleged) active ingredient to the point where barely any molecules remain, or sometimes none with the more “potent” remedies. The concept of the diluted water having some kind of “memory” defies common sense. Another example is the concept of qi (or chi), which underpins most of Traditional Chinese Medicine. It is described as “the natural energy of the universe”. This energy, and the meridians it is claimed to flow through in human bodies, has never been detected. Of course, this doesn’t mean we close the door completely to such possible interventions, but the evidence required to prove that they actually work has to be cast-iron. Currently, for homeopathy and TCM, it is far from that.

2: Be cautious of conspiratorial convictions

The bad news about nefarious conspiracies is that sometimes they do happen. For an example of a medical conspiracy you need look no further than the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. That doesn’t however mean that everything bad that happens in the world is the result of such a thing, and the larger the scale of the conspiracy theory the less likely it is to be true. Unfortunately, the pattern-seeking nature of the human mind can go into overdrive and make connections where they don’t exist. For some extra credit on this topic, read up a little on Hyperactive Agency Detection. In the case of Covid-19, conspiracies such as it being a man-made biological weapon, or a ploy by Bill Gates to put trackers in our bodies via vaccinations are conveniently free of credible evidence, yet we have centuries’ worth of evidence of the transmission and spread of viruses.

3: Give panaceas a pass

In simplest possible terms, cure-all’s cure nothing. The longer the list of conditions that something claims to treat, the less likely it is to do anything.

It should set off your skeptical spider senses even more if an alternative health treatment which has been around for a long time is proclaimed as a cure for a new disease.

For an example of this, have a look at conspiracy theorists’ pin-up boy Alex Jones’ peddling of colloidal silver for Covid-19.

4: Beware of biases

The human brain is amazing, but flawed: “We are emotional, semi-rational creatures, plagued with a host of biases, mental shortcuts, and errors in thinking” – Dr Steve Novella, The Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe.

All of our cognitive shortcomings are further fuelled by social media algorithms which are considerably more likely to push content in your direction which fits your worldview. With this in mind, some self-reflection and humility about your own shortcomings will serve you well.

Be extra cautious of claims which fit comfortably with your worldview.

5: Practice prudence with Presidential proclamations

Many countries across the world have varied their approach to tackling Covid-19. Some are due to factors such as population density, cultural norms, or infrastructure. It’s no surprise however that some of the worst hit countries are those where the leaders don’t pay appropriate attention to the advice of the scientific community. Examples include Donald Trump’s promotion of hydroxychloroquine, Jair Bolsonaro’s recent proclamations about nitazoxanide, or the Chinese Government’s continued pushing of TCM – most notably the especially cruel use of bear bile and other animal products for Covid-19 cures. Whatever your politics, it never hurts to question your Government’s wisdom!

6: Providently peruse problematic premature press

Science communication is difficult, and there’s a conflict of interest between accurately reflecting findings, and garnering public interest. In addition, accuracy is diluted as the conclusions of a study become a press release, then a news story, (with independently written attention-grabbing headline). Currently this is exacerbated by the unprecedented thirst we have for new data in the middle of a pandemic, with many preprints getting press attention before they go through peer review. As such, you should be extra cautious about what you read. It’s prudent to delve behind the headlines and go to the source, and to wait and see what the rest of the scientific community has to say about it before making a judgment.

7: Filter for foolish fallacies

Without delving too much into philosophy, logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that undermine the logic of an argument. Pseudoscientific claims of alternative medicine proponents almost always fall into some of these. For example:

- The argument from authority: When ‘real’ doctors (or other experts) are used to try and support fringe beliefs. Examples include the two Doctors who misrepresented statistics to try and argue that Covid-19 had spread further than expected, and therefore wasn’t as serious as first thought, or the well-known descent of multiple Nobel Prize winning Linus Pauling into unfounded claims of the benefits of vitamin C megadosing.

- The argument from popularity: Most commonly used when there’s no rigorous data to prove something works, the alt-med proponent will fall back to patient testimonies, or cite the fact that many people use their product so it must be good. Check out Homeopathy UK’s twitter feed for frequent examples.

- The appeal to ancient wisdom: In simple terms, saying that a medical intervention has been used for thousands of years is frequently seen as a plus. It should however always ring alarm bells. Pre-scientific era medicine was not known for its effectiveness, and such an argument should not be compelling. Traditional Chinese Medicine is certainly one of the worst culprits here.

- The appeal to nature: This is used in two ways. Firstly, there’s a sentiment that things which are ‘natural’ are always good for you, despite the fact that the world is teeming with incredibly dangerous flora and fauna. On the flipside, it’s also used to denigrate modern medicine, or anything which requires some form of scientific intervention to produce. Neither are good arguments.

Look out carefully for these and others when evaluating any medical intervention.

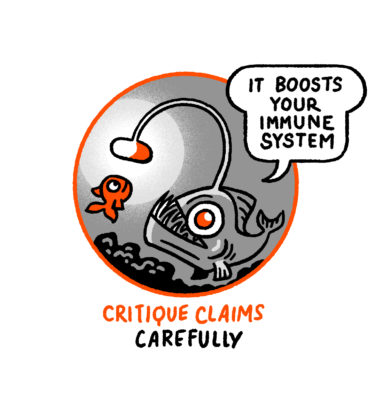

8: Critique claims carefully

Medical treatments will generally fall into one of three areas: prevention, cure, or treatment. A claim to cure anything (particularly a virus like Sars-Cov-2) should always set off alarm bells as it’s highly unlikely. If you hear [miracle cure x] kills [disease y] in a petri dish it sounds impressive, but is almost entirely meaningless (napalm will kill cancer cells for example, but we wouldn’t recommend it for your tumour). Claims to treat or mitigate the effects of a disease are more common. We’re learning more and more about how to treat severe cases of Covid-19, but still have a long way to go. Anything that claims to be able to treat it right now should be met with the utmost of skepticism. In terms of prevention, don’t be fooled by alt-med claims of ‘boosting your immune system’ – it almost always shows a lack of understanding about what the immune system does. That being said, vaccines will ‘train’ your immune system, which is kind a ‘boost’ of some sort, and this still remains our best hope for keeping Covid-19 at bay. A general rule of thumb to apply here is that the more dramatic the claim, the less likely it is to be true.

9: Be pharma-logical

There’s a constant campaign by proponents of alternative medicine to try and discredit mainstream medical practices. Any time you see the term ‘Big Pharma’ being used, it’s usually paired with an attempt to sell some snake oil, or perhaps talk you out of vaccinating your children.

Let’s be very clear though, pharmaceutical companies are consistently awful – read Ben Goldacre’s Bad Pharma for more on the subject. That shouldn’t however fool you into thinking that everything they do is bad, or that the alternative medicine on offer would be of any use. Be reasonable and balanced in your approach.

10: Separate pseudoscience from science

Pseudoscience is akin to a wolf in sheep’s clothing. It has the look and feel of legitimate science; There are actual studies. Published in journals. Peer reviewed. In the case of medical interventions, there are legitimate health professionals who genuinely believe and actively promote them. Fortunately there are almost always some red flags that can be spotted with a little investigation, and points 1-9 above will help you along the way with that. For some quick assistance, check out the Skeptoid podcast’s episode on How to spot pseudoscience, or for a deeper dive, read the The Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe.

In conclusion

The waters are murky, but a little bit of critical thinking will provide some much-needed illumination. Be careful what you believe, and look out for your family and friends too.