I listen to a lot of podcasts. Whenever I’m working, or doing household chores, or popping to the shop or out for a run, it’s rare to see me without earphones in, listening to people talking about things.

It’s a medium I love, and one I’ve quite a lot of experience in: idly totting up shows the other day, I realised I’ve recorded nearly 500 shows, over a span of 12 years. In that time, podcasting has changed a lot. In 2009, it was something niche enough that you had to explain to people what a podcast was; now having a podcast has passed into being a cliché, especially for white guys like me.

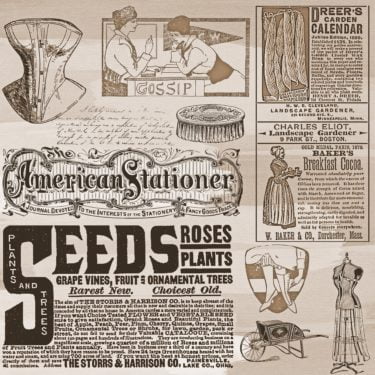

That explosion in popularity over the last decade has seen something of a gold rush, as people who would otherwise have sought an audience through more mainstream publications set up their own show – hello Alec Baldwin, Megan Markle and Prince Harry – while mainstream publishers themselves arrived into podcast-land and declared it theirs faster than a 19th century British general stepping off a boat in India. Where once the iTunes podcasting charts were filled with independent shows by makers you’ve never heard of, recording in bedrooms on cheap headsets, the charts now are filled with podcasts from the BBC, the Guardian, the New York Times and NPR.

With any gold rush, what you really need is some gold. For a long time, that gold when it came to podcasts was simply ears – the number of people you could reach, and how many iTunes stars you could persuade them to give you as a rating. When you accumulated enough stars… well, nothing happened. Monetisation was a long way off – at best, you could sell them a T Shirt or a mug. But then, in 2013, Patreon came along and allowed listeners to make small micropayments to finance the shows they love (and, indeed, the publications they love – check out patreon.com/theskeptic if you’re enjoying our work!).

Patreon isn’t the only source of income for podcasts – as avid listeners will be aware, running ads on podcasts has become commonplace. These come in several different formats: the pre- and post- ad, where a clip of audio is inserted at the beginning or end of the podcast; the mid-show ad, where your podcast stops for a moment and plays an audio clip; and the copy-read ad, where your favourite podcast hosts stop talking about the thing you like them talking about, and start talking about products and services instead.

A necessary evil

To be clear, this isn’t an anti-advertising article: I’m someone who spends a lot of time reading about and talking about how the traditional media works, and how it is (just about) financed, so I understand that ads are often a necessary evil, and equally keeping the lights on is a very reasonable thing for podcasts to do. Some people make their living doing podcasts, and advertising I’m sure is a decent chunk of that. I get it. I personally find ads in podcasts annoying, but I also find ads annoying when I watch TV, and when I read newspapers, but in all cases I’m willing to accept it as a necessary trade off to get access to the content I’m interested in.

Where things get more ethically dubious, as I’ve covered elsewhere, is when the article you spent time reading was actually provided by a commercial company rather than written and edited by journalists – that’s native advertising. Native advertising undermines the trust you place in your newspaper, because you can no longer be sure whether something was published because it is a genuine story, or because a company paid the paper to pretend it is a real story.

In my opinion, copy-read ads are the native advertising of the podcast world, and they get way too little scrutiny.

I was recently listening to an episode of Pod Save America, from Crooked Media. It’s a political show in which several former staffers in the Obama administration talk through the latest political news from the US. Under Trump, there was always a lot to talk about, and I’ve been a regular listener for a few years. I’ve therefore lost count of the number of times their political analysis would pause for a moment for them to talk about the underwear brand they’re wearing, or where they got their mattress from. It’s incredibly jarring, because these people who were just talking authoritatively and informedly about how the American political system works and where it is breaking down are now slipping straight into infomercial mode, reading ad copy about how wonderful a company paid them to say it is.

It’s possible they really believe what they’re saying. It’s entirely possible that they really do eat Hello Fresh every night, and sleep soundly on a Casper mattress, and maybe they really do hate going to the post office and so find Stamps.com a godsend with its free digital scale. I’ve honestly no idea what their opinions on those services are, because it is a fact they’re paid to say they’re great. That transition from trusted expert to door-to-door salesperson is jarring, and it’s bad enough when they’re promoting things that are uncontroversial, like mattresses… but it doesn’t stop there.

Magic spoons and bee supplements

“Magic Spoon cereal is high-protein, low-sugar, keto-friendly, gluten-free and GMO-free” Pod Save America told me recently, before talking at length about how great this cereal is and how it comes in so many flavours. In doing so, they joined the ranks of influencers who rave about Magic Spoon for money, including testimonials on the Magic Spoon website from Kelly Leveque, the holistic nutritionist and wellness expert; John Durant, author of the Paleo Manifesto; and Katie Wells, founder of WellnessMama.com. As they promote the cereal, there’s no question from Pod Save America’s hosts about whether it’s actually a good thing that the cereal is GMO-free, or whether it’s so important for people to eat gluten-free. In the place of such scrutiny, we hear personal experiences about the product – because that’s what the advertisers have paid to for the hosts to share. I imagine a personal experience like “anti-GMO is an anti-science position, and you don’t need to be gluten-free unless you have coeliac disease” is not what the advertiser is looking for, and sharing it would mean the end of that advertising partnership.

The show regularly reads ads for the Noom dietary program, which claims to use psychology-based evaluation to determine the right diet for you. It’s a weight-tracking app that costs $25 per month. The hosts say they love it. They also tell us they love their Four Sigmatic mushroom coffee, the organic drink that supports your immune system.

And boy do they love to tell you about Athletic Greens, your “Daily Dose of Nutritional Insurance”, which are “paleo and keto friendly” supplements designed to “support immunity, energy, digestion and recovery”. They are apparently “filled with superfood complex including adaptogens and antioxidants”, plus “more than 75 vitamins and minerals”. Are these products actually good for you and worth buying? Your favourite podcast hosts are willing to say yes to those questions, for money, so that should put your mind at rest enough to spend £90 on a 30 day supply… or you could use the discount code for 10% off your first purchase that’s the discount code for 10% of your first purchase.

On a recent show, I heard an ad for Beekeepers Naturals, during which the hosts told us, “Beekeepers Naturals is on a mission to reinvent your medicine cabinet with clean remedies that actually work. It naturally supports immune health and contains powerful antioxidants making it your daily dose of defence when it comes to naturally supporting your immune system”. It got worse, the hosts went on to explain that Beekeepers Naturals also sell “B LXR Brain Fuel”, which is “a productivity shot that supports clear thinking, with science-backed adaptogens”.

Clean remedies? Naturally supporting your immune system? Brain Fuel? This is the language of Goop and Infowars, and it’s coming to you directly from the voices you trust and have affinity for.

Beekeepers are a supplement company who sell products like the $75 “Beegan Pharmacy Kit” (note, that’s Beegan, not ‘vegan’ – their products are not vegan, merely associating with the goodwill their target market has towards veganism), which includes some superfood honey, a throat spray, and their brain force plus – sorry B LXR Brain Fuel. They market that with the claim “Fight jetlag, defend your immune system, and get energised”.

They sell an Immune Rescue Kit for $80, and a Family Immune Support Essentials pack for $83 which includes four throat sprays (which the founder of Beekeepers Naturals, Carly Stein, told Business Insider can be used to “prevent any sort of illness or recover when you have a sore throat, cold, or the flu”) and a bottle of cough syrup. The sprays contain bee propolis – a kind of waxy resin created by bees. There’s no good evidence it has the health benefits claimed by the company, as best as I can see – certainly not for being able to “fight jetlag”, or “support clear thinking”, whatever that means.

This is wellness nonsense – mountains of it, entire Goops of it – promoted to you by the very people you listen to regularly and trust.

Undermining credibility

This is an issue, I believe, that all podcasts who run copy-read ads need to think long and hard about, and it isn’t just reserved for the claims which are obviously pseudoscientific. Some of the most popular skeptical podcasts out there today aim to train their listeners to think critically, and by extension those hosts become people their listeners trust and respect, people whose word listeners are inclined to believe. Those shows will transition directly from sharing their expert opinion on an issue of science or skepticism, to, in the very next breath, telling their audience how amazing their investment-tracking app is or how life-changing their new mattress has been. The ethical concerns here should be pretty clear, and the only thing clouding them is that seductive income stream.

Full disclosure here, because I don’t want to be a hypocrite: I regularly appear on God Awful Movies, a podcast that runs copy-read ads, and I take part in those ad reads. It’s something I’ve thought a lot about, as it’s a show I dearly love doing, and I came to the conclusion that I feel comfortable with their ads, for a couple of reasons. Firstly, the show vets their ads for pseudoscience, and doesn’t take ads that are questionable – they even run potential advertisers past Dr Alice Howarth, Deputy Editor of The Skeptic, for her opinion on the science. When in doubt, they refuse the ad.

Secondly, and perhaps more pertinently, their copy-read ads are always, 100% of the time, presented in sketches and skits. Partly that’s because it’s more interesting to listen to a comedy bit than it is to sit through someone giving you an opinion they’ve been paid to pretend to have, but it also enforces the barrier between editorial and commercial. Ads are read by characters the people on the show play, and not the real people. It’s clear to all that the opinions expressed in the ads are part of a script, because we all recognise and inherently understand that sketches are scripted; that’s not necessarily the case for those ad reads on Pod Save America. When I’m on God Awful Movies, they go out of their way to make the line clear between the times I’m giving my opinion and the bits where I’m playing a character in a sketch they wrote.

I’m not saying it’s a perfect solution, or that there even is a perfect solution here, but I do think it’s something podcasters need to give some serious thought to – especially if their aim is to educate their audience and to encourage critical thinking. It’s hard to do that while segueing into an untrue story about how wonderful your new toothbrush is. At the very least, all podcasters need to have a strict vetting process on who they advertise, and what they’re being paid to say they believe.

Right now, podcast advertising is an area that’s less than a decade old, and the advertising offers often end up being pitched to people who started a show in their bedrooms because they were passionate about something, and an audience found them. Even the most worldly of podcaster in that situation might not be fully equipped to understand when and how to push back against the demands of their advertisers.

But if podcasters who care about their integrity set clearer lines, they have the opportunity to shape the rules and norms of podcast advertising. Without those clear lines, the advertisers will take as much as they can, because that’s what advertising does – the value, for them, is in the hosts’ reputation, and voice, and the trust they’ve built with their listeners.

If those hosts don’t work hard to protect and preserve the trust of their audiences, nobody else will. When it’s gone, it’s gone… and even the advertisers won’t want them any more.