This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 14, Issue 3, from 2001.

When you think of chess grand masters, you think, by and large, of thoughtful, rational people. You don’t expect to find one speaking out for a very odd brand of historical revisionism. But Garry Kasparov is a high-profile spokesman for New Chronology, a Russian conspiracy theory of history that’s gaining a startling amount of credibility there.

New Chronology does have solid mathematical roots. It’s the work of a group of notable Russian mathematicians, most notably Anatoly Fomenko and Gleb Nosovski, professors at Moscow State University, building on the work of a man named Nicolai Morozov. While imprisoned for his role in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, Morozov drew up chronologies demonstrating that the reign lengths and sequences of the Old Testament kings from Rehoboam to Zedekiah were almost identical to those of the Holy Roman Emperors from Alcuinius to Justinian II, implying that these were actually the same set of historical rulers, mentioned in two separate sets of historical records and mistakenly assigned to different dates over 1,000 years apart.

Fomenko and his colleagues have expanded on this by developing the concept of the “dynastic function”, the pattern of reign lengths and sequences which can be statistically compared. They claim to have compiled a “complete list of fifteen-ruler successions from 4000 BC to 1800 AD, drawing from all the nations and empires of Western and Eastern Europe, and stretching back into antiquity through Roman, Greek, biblical, and Egyptian history,” and say that this shows not only many stretches of apparent identity between the Old Testament and Roman-German history from the 10th to 14th-centuries, but also a single large pattern that repeats itself four times from roughly 1600BC to 1600AD. This, they reckon, shows that “history”, as generally taught, is a patchwork of misdated sources, with many historical figures misidentified as more than one person. As examples: Jesus Christ was in fact born in 1064 AD (no, I don’t know where they’re dating the AD from) and is the same person as Pope St. Gregory VII. Apparently one of the Three Kings in mediaeval religious pictures is often shown as a woman. She, say the New Chronologists, is the ninth-century princess Olga, who converted Russia to Christianity (which, by the way, was identical with Islam until the 16th century).

The mathematics are impressive, though more orthodox historians question the data used for the statistics. There are many uncertainties even in the standard chronology, and there are claims that Fomenko and his colleagues have selected their data to better fit their theory. Which, of course, they deny. None of that would really amount to much more than an academic squabble if it weren’t for the growing political ramifications involved. The theory’s more extreme adherents are developing a Russian-supremacist interpretation. They would like to believe that Russia’s empire once stretched all over Eurasia.

This is a resurgence of a very old phenomenon, that I’ve decided to call cryptohistory, mainly because I’ve been interested in it for quite a while and had to find a term for it (1). It has close ties to conspiracy theory, since many conspiracy theories involve reinterpretation of history to show how it’s been manipulated by whichever cabal of conspirators the theorist deems responsible. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, still in print as supposed fact, is a classic example, claiming to detail the plans of the Jewish cabal who intend to secretly dominate the world. A browse round the more paranoid areas of the internet will unearth many, many more examples, varying widely in coherence, sanity and basic literacy.

Not all cryptohistories are necessarily conspiracy theories, although a large number do find it necessary to invoke conspiracy of one sort or another to explain why their interpretations aren’t widely accepted. But many of them are simply revisions or alternate explanations, and some may even be correct. There seems, for example, to be good historical evidence that the canonical Wicked Uncle of English history, Richard III, was not responsible for the death of his young nephews, the Princes in the Tower, and that in fact they outlived him only to be secretly assassinated by the next king, their brother-in-law, Henry VII. Who, when it came down to writing the histories, had the advantage of better publicists and a kingdom full of people who decided it was better to keep their suspicions to themselves and survive. (2)

Actual attempts to re-date history itself are rare, but the New Chronology isn’t the only one. There’s a wide spread of them, ranging from Immanuel Velikovsky (3) (as a sideline from his usual planetary demolition derby) and, more recently, David Rohl (4) in Egyptology to a German called Heribert Illig who suspects that Pope Sylvester II added 300 years to the history of Europe, inventing Charlemagne in the process and confusing modern historians by thus creating the period known as the Dark Ages in which not much happened. Unfortunately, Illig’s work hasn’t yet been translated into English, and since my German is nonexistent I can’t evaluate this further, though he apparently claims that standard chronology has problems with both carbon-dating and parallelism among European, Indian, and Chinese history that his theory can explain. If anyone who can read German cares to investigate further, I’d be delighted to know why Pope Sylvester did this.(5)

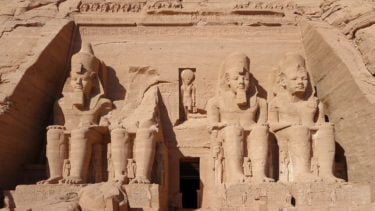

Egyptology and Biblical history seem to be the main haunt of re-daters (6), who often try to link them. Sir Isaac Newton was perhaps the first, and certainly the most famous, to devote himself to reconciling the Bible with other historical documents. Nowadays, Velikovsky and Rohl are the most notable in this area. Velikovsky’s second book, Ages in Chaos, argued for a shift of about 500 years in the dating of Ancient Egypt, which he believed would bring it closer into line with events in the Bible. This theory was roundly ignored by Egyptologists, not least because the events he wanted to bring into line included catastrophic near-misses of the Earth by various careening celestial bodies, but Velikovsky has many enthusiastic followers to this day. Rohl is more scientifically respectable. He advocates, at least in his mass-market publications, a much smaller time shift; re-dating the 21st and 22nd dynasties to run concurrently rather than consecutively. He offers what seems (to me at least) to be convincing evidence of misdating. Apparently this isn’t an original theory; it’s been a minority opinion for years, particularly among European Egyptologists.

The movement towards wider social history in the last century has brought a golden age for cryptohistory. Until Marx and Engels famously expanded historical analysis to include social and economic conditions, history was mainly confined to political and military affairs. The rise of feminism has led to the recent prominence of women’s history, which has a fringe of its own, most notably in the likes of Marija Gimbutas and Riane Eisler, with evil male-chauvinist Indo-European invaders wiping out primordial Goddess-worshippers and conspiring to enslave women for the past few thousand years (7). Other groups of people have developed particular interests in their history as an offshoot from and a spur to their campaigns for civil rights – the histories of both black and lesbian/gay people are growing and occasionally controversial fields of study. Again, they have their extremists. Afrocentric history casts Africa as the cradle of all civilisation. The Ancient Egyptians were black, and their culture and knowledge was stolen by whites, who then denied and covered up this mass theft. Again, this feeds off recent archaeological discoveries and historical re-evaluations of African civilisations. Given the sad history of racial prejudice it’s very easy to claim a white conspiracy to denigrate African achievements and hide The Truth.

History is a subject that’s ripe for such reinterpretation. The written records we have are limited and biased – notably, and obviously, towards those people who actually left records, the literate and powerful, who naturally had their own agendas. New perspectives can add valuable understanding, or hint at new possibilities, but the gaps in our knowledge are so large that it’s easy to fill them with guesswork and opinions that only reinforce what we want to believe.

This is nothing new, of course. As long as there’s been history there have been people putting a spin on it, usually to flatter themselves, their community or whomever happened to be in charge at the time, but sometimes in pursuit of stranger agendas. Erich von Däniken’s reinterpretation of ancient history to include alien astronauts was the 1970s version, but there are plenty of earlier examples (usually Biblical). These include writers such as the rather alarming Comyns Beaumont, who was determined to prove that all the events of the Bible actually occurred in Britain and produced beautiful maps of the Home Counties with place names from Israel and Palestine (8). I’m also tempted to include Joseph Smith Jr, whose Book of Mormon has Jewish tribes battling across the Americas. This apparently puts devout Mormon scholars in a bit of a spot, since the Book of Mormon is divinely inspired and therefore unarguably accurate, though unfortunately failing at any point to agree with the archaeological record. Though it is the only theory I’ve ever seen that accounts for the Yiddish-speaking Chief in Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles.

Another modern version, with plenty of recent publicity thanks to the David Irving/Deborah Lipstadt trial, is Holocaust revisionism. Antisemitism is prominent in many cryptohistorical theories, perhaps due to their conspiracy theory links. For instance, many versions of Afrocentrism are strongly antisemitic, and the Nazi obsession with reinterpreting history as the preserve of noble, blonde ur-Nazi Aryans and scheming Jews is well known. The Anglo-Israelite Comyns Beaumont, mentioned above, was pretty-much overtly writing to prove that all this Biblical stuff was really the work of noble Northern Europeans. After all, who could God’s Chosen People be but the British?

This isn’t just playing with interpretations, though; there are wider political implications. Cryptohistory isn’t just confined to fringe Web sites. People use history. A shared history, whether it’s true or not, is a cohesive force. The rise of social history is entwined with the politics of society – Marx and Engels were the intellectual force behind Communism. The history of feminism, and of social activism in general, is closely bound up with the practice of same – knowing about the struggles of people you can identify with provides inspiration and strength, as well as knowledge. As they say, you have to know where you’re coming from to know where you’re going. But this can be horribly misused. Look at Communism. Look at Nazism. Read any newspaper, and note how often history is used to justify present atrocities.

History is vulnerable to hijacking by those with agendas of their own, and cryptohistories, with their lack of academic credentials and support, possibly more so. As an example, Rohl’s new Egyptian chronology is supported by many who wish to see the Bible as a historically accurate document, a hope that mainstream archaeology in Canaan and Israel doesn’t support. I am told that it also delights white supremacists, since his theory has Egyptian civilisation founded by invaders from Asia Minor, who became the modern Jews/Arabs, rather than by Africans.

Cryptohistories often have a great deal of emotional appeal, for various reasons. They can offer simple, easily understandable explanations for complex injustices. Why are women considered inferior? Because the nasty Kurgans invaded and enslaved everyone who didn’t think that way. Why are you not powerful, famous and loved as you deserve? Because there’s a conspiracy – of Jews, of Masons, of white people, of whichever scapegoat is convenient – against you and yours. They can offer support for the status quo by flattering the powerful, or soothing or sidelining the powerless. They can entertain – the excitement of discovering lost civilisations, the thrill of being one of the few in the know.

Returning to New Chronology with this in mind, it’s no surprise that it’s so popular in Russia, considering the present depressing state of the CIS. It gives them a glorious past and more, it gives them a glorious past which has been unjustly and cunningly hidden until rediscovered by brilliant Russian scholars. Apparently this mythical history has become so popular in Russia that some school districts insist that it be taught as truth, and history professors are worrying about an influx of first-year university students who’ve never learned anything else. And I recently heard that President Putin wants New Chronology to be taught in Russian schools. Given the age-old human tendency to invent the histories we want, and then use them to justify our actions, perhaps we should begin to worry.

Notes

- The Skeptic’s Dictionary has an entry for “pseudohistory” at http://skepdic.com/pseudohs.html. I decided not to use the term, since it only covers the extreme end of the field I’m interested in and some cryptohistories are more respectable and better supported by the evidence than that term would suggest.

- Too many books for and against Richard’s guilt to list here. Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time (1951) is a good light read, presented as a modern-day detective story using historical evidence. I also like AJ Pollard’s Richard III and the Princes in the Tower (1991), a well-balanced account.

- Velikovsky’s books on historical redating are “Ages in Chaos” (1952), Peoples of the Sea (1977) and Rameses II and His Time (1978). Most of his unpublished work is available on the Internet.

- David Rohl: A Test of Time (Arrow, 1996) and Pharaohs and Kings: a Biblical Quest (Crown, 1997).

- Heribert Illig: Wer Hat an der Uhr Gedreht? (Econ Verlag, 1999). A discussion of Illig’s work from a postmodern point of view: http://www.philjohn.com/papers/pjkd_h02.html.

- “The Revision of Ancient History – A Perspective” by P John Crowe is a massive overview of various attempts to redate Egyptology. Rather heavy going, I’m afraid, and no orthodox Egyptologists are represented.

- Riane Eisler’s The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future (Harper San Frarncisco, 1988), began the modern pseudo-feminist cult of blaming everything that’s wrong with modern society on prehistoric invading Indo-European tribesmen. Dr Marija Gimbutas wrote, among others, Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe, 7000-3500BC: Myths and Cult Images (University of California Press, 1982) and The Language of the Goddess (Harper San Francisco, 1989), though most of her fellow archaeologists didn’t (and still don’t) agree with her conclusions. See http://www.debunker.com/texts/goddess.html for excerpted arguments against her claims.

- Comyns Beaumont, Britain: the Key to World History (Rider & Company, 1947). “Jerusalem” is really Edinburgh. Goliath came from Bath. What more can I say?