In the Hippocratic chapter: Diseases of Young Girls written throughout the 4th and 5th centuries BC, it is written that “the menses sometimes suddenly appear abundantly at the end of three months, in clots of black blood, resembling flesh; sometimes ulcers of the uterus ensue, requiring much attention”. In fact, the condition was so well recognised back then that the Hippocratic authors recommended women with dysmenorrhoea (a condition which describes particularly painful cramps associated with menstruation) should aim to have children as early as possible due to the association between delayed motherhood and problems with menstruation.

In fact the condition that was recognised then, although not named, is believed to have been endometriosis. Reports of the condition have been found throughout history with descriptions from Plato in Ancient Greece and Pliny the Elder and Galen in Roman times. In the Middle Ages it was recorded that women would pass out from the pain – an observation also made by those Hippocractic authors several hundred years earlier – and in the 12th Century a treatment of ‘‘a powder be made of the testicles of a fox or a kid and that this be injected (into the vagina) by means of a tampon’’ was suggested for “suffocation of the womb” – a condition we now believe to be endometriosis. By the 16th Century, the condition was referred to as hysterical fits and the pain was described as so bad that women believed themselves “near death”.

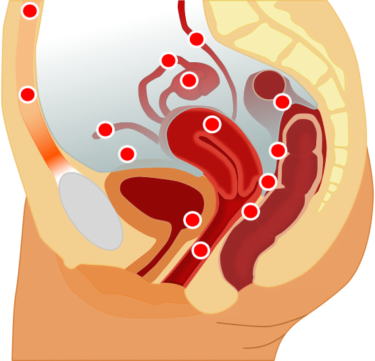

Endometriosis continued to be described in the next few hundred years but it wasn’t named until after 1860 when Karl von Rokitansky identified endometrium-like tissue growing outside of the womb and microscopically forming characteristic chocolate cysts. This endometrium-like tissue growing in the wrong place in the body causes symptoms including pain in the lower abdomen and back, pain during or after sex, pain when using the bathroom during menstruation, feeling sick or suffering with constipation or diarrhoea during menstruation, severe period pains and difficulty conceiving. Some people with endometriosis have relatively mild symptoms, but for many people the pain can be completely debilitating.

Almost 2,500 years since the passage in the Hippocratic Corpus, a report published in October 2020 by an All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Endometriosis described the landscape of endometriosis diagnosis and treatment in the UK. They found that although 10% of women of reproductive age have endometriosis – including 1.5 million people in the UK and 176 million globally –the average waiting time from symptom onset to diagnosis in the UK is 8 years. Prior to diagnosis 58% of patients visited their doctor about their symptoms more than 10 times and 41% make over 15 visits. The APPG considered responses from a self-selecting group of people and garnered nearly 11,000 eligible responses. This isn’t the first study to find such long delays between symptom onset and diagnosis of endometriosis and in fact the longer the delay to diagnosis, the greater chance of the need for emergency hospital visits relating to the condition.

The report made it clear that raising awareness, and a need for all medical professionals to have the ability to recognise the symptoms of endometriosis were important factors in addressing the delays in diagnosis. Still, in the launch event for the report, Minister for Mental Health, Suicide Prevention and Patient Safety, Nadine Dorries, who is responsible for Women’s Health Strategy, said:

“that is partly our problem as women – we don’t talk enough… I think women actually have a responsibility when they go to the GP’s practice not to take no for an answer, not to be fobbed off by a doctor. They do not push back, they don’t challenge, they’re not confident enough to raise an issue, and so they’re very easily dismissed.”

It might well be true that a lack of frank discussion is contributing to diagnostic delays, but this over simplification, yet again, puts responsibility for issues with women’s health care back on to the very women who are most harmed by these issues. Time and time again, studies have shown that the medical and research professions fail women, and other marginalised groups, particularly when it comes to identification of conditions causing pain. We know that women are more likely to be given sedatives than pain relief for pain, they’re 13-25% less likely to be given opioid pain relief for pain than men and they’re more likely to be misdiagnosed when having a heart attack. Women talk about how their doctors disbelieve them when they present with severe pain symptoms either in GP clinics or in A&E.

Here we have another report that confirms the long diagnostic delays for people with endometriosis. Many studies have reported a lack of research into the condition, and diagnosis still frequently relies on invasive laparoscopy (key hole surgery) to find endometrium-like tissue growing outside the womb. The treatment for endometriosis, too, is simply not good enough, with treatments largely targeted at either stalling the growth of endometrium-like tissue using hormonal treatments that have a limited impact on pain and stop working as soon as the treatment is stopped, or at cutting away lesions in the pelvis using surgery. Patients who undergo surgery to remove these lesions are likely to recur at a rate of 40-50% within 5 years. Even hysterectomy only helps with endometriosis that affects specifically the organs which are removed with this surgery, but endometriosis commonly causes lesions to grow closer to the bladder and bowel, and even other parts of the body entirely.

It makes sense, then, that the report by the APPG recommends not only to reduce the diagnostic delay and to increase awareness for endometriosis, but also to increase research into the condition in order to improve both the diagnostic tests available and reduce the need for invasive surgery, and to improve treatment options for the 10% of women of reproductive age who suffer with the condition.

But in September, just one month before the report was published, Nadine Dorries said in Parliament that there were “no [current] plans to reduce the diagnosis time for endometriosis”, and “there has been no assessment of improvement to the diagnosis and management of endometriosis since the publication of the 2018 [NICE] quality standards.” She has yet to say whether this report changes anything.

To understand exactly why diagnostic delays are so prevalent and treatment options so variable, it’s important to consider some of the myths relating to endometriosis – many of which are perpetuated by the medical profession. For example, while many believe that severely painful period pains are normal, it is long been part of medical history that women are considered to have lower pain thresholds and a greater propensity to medical neurosis. But even if those things are true (an idea which is lacking robust evidential support), the pain women feel with conditions like endometriosis is very real, and can be very debilitating. The result of the prevalence of these ideas are that even if women feel able to approach severely painful periods with their doctor, they run the risk of dismissal from doctors.

Another misconception is the idea that endometriosis only causes painful periods – research from the World Endometriosis Research Foundation found that 50% of people referred for bowel issues to gastroenterology actually had endometriosis. It is therefore not only important that medical experts in fields other than endometriosis are aware and able to recognise the possibility that symptoms might indicate endometriosis, but also that endometriosis-specialist gynaecologists are available to support patients with symptoms that span more widely than dysmenorrhoea.

Many misconceptions relating to endometriosis include myths relating to fertility – both that endometriosis always causes infertility (in fact 20-30% of endometriosis sufferers are affected this way) and that endometriosis is only worth considering in patients who wish to conceive in their future. This latter belief was underscored in the APPG report in testimony from patients like ‘Lucy’, who said:

“It felt like my fertility was taking priority over my own health and pain. Often the woman or the person gets lost, because the condition is so focused on menstruation and fertility, and actually it’s about your ability to function and manage your pain and your life.”

However the APPG report also indicated that fewer than half of people with endometriosis were asked by their doctor if their fertility was a priority for them.

Another myth relating to endometriosis is that pregnancy will cure the condition – an idea that the report identified as having been repeated to people with endometriosis by medical professionals. It should go without saying that pregnancy should not by recommended as a treatment for any condition.

Relatedly, misconceptions that either pregnancy or hormonal treatments will cure endometriosis are so pervasive that patients miss out on treatments that might actually help – while hormonal treatments can suppress the symptoms of endometriosis, they do not cure the condition and cessation often means symptoms will return. For people who are considering the chance to have children in their future, surgery should be considered as an early option to prevent the damage that might cause infertility (although the mechanisms by which endometriosis causes infertility in the cases that it does remain unknown).

Ultimately, endometriosis is a condition that affects an awful lot of people, in significant ways that can severely reduce quality of life, increase risk of hospitalisation and reduce fertility in some cases. We need further research into how to easily diagnose the condition, support medical professionals in a range of specialties to recognising the symptoms, increase awareness of both the condition and the myths around it, and we desperately need to bring the diagnostic delay down.