I don’t mean to shock you and I hope you’re sitting down for this but there’s a lot of false information on the internet. Not only that but users have been ripping things right out of context and sharing them with reckless abandon, for thousands of innocent victims to react to, only to be exposed as naive dupes once the true context is revealed. Why, only this past week it transpired that… nope, I can’t keep this up.

There is no single, correct context we can place something in to reveal everything worth knowing about it. We don’t have to throw our hands up in despair, however, or retreat from all commentary in case we make a mistake. The fact that pictures and texts can be taken out of their various contexts and spark countless responses in a matter of hours is a reality of our age and is something we can learn to live with.

Different types of contextualising information can be illuminating in their own worthwhile way and sometimes a thing’s reception history – the different ways it has been used and interpreted – can tell us more than an analysis of the thing itself. Let’s have a look at one recent example, not to establish hard facts (not least because there may be more waves of those to come) but to see how different layers of context can add to our understanding.

The thing

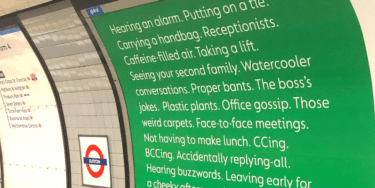

A poster advertising disinfectant. The text lists features of working in an office such as “plastic plants” and “accidentally replying-all”. One photograph of the advert which was shared widely on Twitter contained only the text and didn’t mention the brand, so many initial responses were shaped by the assumption that it was part of the UK government’s campaign to encourage people who have been working from home to return to their usual offices. I’d characterise the prevailing mood as one of mocking anger.

Often when something which has been widely shared and discussed is exposed as a fabrication, there’s a wave of retractions, expressions of regret or embarrassment, and a fair few declarations that only a fool believes everything (anything?) they see on the internet. In this case, perhaps because this was a misunderstanding rather than a fake, much of the mockery transferred to the company who commissioned the advert, while the anger at the government messaging which it resembled continued. Many people (justifiably, in my opinion) reserved the right to use this opportunity to vent their feelings on a prominent and contentious issue, even though the initial stimulus what not quite what they thought it was.

Context One – location, audience, purpose

This is what could be considered the “correct” context: the “actually, I think you’ll find…” of the matter. It’s a poster at a public transport hub so likely to be aimed at people who are already commuting to work rather than those yet to be coaxed out.

The point behind the advert, it can be assumed, is to raise brand awareness. There are several aspects to this and the poster may not be intended to fulfill all of these functions, but generally advertisers want to make people aware of their product, form associations with certain qualities and values, increase the amount that people use, or make people think of their brand in particular when the need for it arises.

When trying to keep something at the front of people’s minds, it can be useful to tap into current trends (even controversies) and try to chime in with people’s emotions. Which brings us to…

Context Two – advertising in a crisis

There seems to have been a trend over the past couple of years for advertisements to list associations with a particular concept. These might be reminders of the small joys of going to a familiar place or perhaps they place a brand at the heart of a common experience. Often these lists will be delivered in a warm, friendly regional accent and they have an irritating tendency towards bad rhymes.

Amid the worries, separations and bewildering abnormality of 2020, appealing to this feeling of togetherness and shared values and experiences has been a popular strategy for brands which don’t want to appear tone-deaf or encourage us to do things which we aren’t currently allowed to do. In this context, our poster appears less like a laughably unrelatable love-letter to the office, and more like a neutral, shared-experience appeal to “think office; think disinfectant”.

Even though it’s playing on customers’ mixed feelings about current events, there’s no reason to suppose that it was directly informed by the government’s campaign for a return to offices.

Context Three – The government’s campaign for a return to offices

Didn’t I just say that this was irrelevant? Well, even if something isn’t created in direct response to a political context, we can still explore how political and cultural messages can interact, influence each other, perhaps deliberately oppose one another, and how all of this can play out in a medium such as advertising.

On a simple level, this advert would likely not exist in this form if the official advice to work from home where possible was still in place. Again, companies don’t want to risk being wildly out of keeping with what’s allowed and accepted at a particular time. More subtly (and this is where I may sound like a conspiracy theorist) this need to take cues from current events and prevailing sentiment can cause advertising to be surprisingly in-step with what might be termed more establishment positions.

Think back to Queen Elizabeth’s last jubilee, for example. You’d have been hard pressed to find a shop window display, in England at least, which didn’t have a Union flag or bunting or a cushion with a bulldog on it. Without the need for government directives or any centralised plan, companies responded to what they assumed the majority of customers were feeling, resulting in a consistently patriotic feel on every high street. Norms – even new-normal norms – are powerful things and we can find behaviour-shaping messages echoing from all manner of unexpected directions.

These examples are just some of the many contexts we could explore relating to this one text. The first type of context may seem the most factual, in that it provides the clearest line of causation from intent to creation, but that doesn’t necessarily make it more important or worthy of analysis. There’s always more background to explore and so trying to fully place something in context before reacting to it would be futile. Equally, writing off a text and people’s reactions to it because it was “taken out of context” would waste an opportunity to think through why something has the shape that it does and why it invokes those responses.

Every one of us will inevitably miss something important in our initial reactions and there’s no need to feel ashamed or defensive about this. We really do lose something when the most basic facts – the “well actually” of when, where and why a thing was created – are treated as the end rather than the beginning of the discussion.