Back in my first article, I expressed a passion for the intersection of skepticism and ethics. I gather many skeptics have trouble reconciling ethics with a scientifically informed, materialist worldview. I suspect that this metaethical challenge is just one instance of a larger problem concerning the nature of value.

Ethics is just one of many systems of knowledge that centers on evaluative judgments, meaning judgments about which things have value. Our evaluative frameworks shape every moment of our lives, so it’s ironic that we struggle to answer basic questions about value like “where does it come from?” and “do all things have it, or only some?”.

The field of value theory is vast, and satisfying answers are hard to come by. I personally have come to believe we should adopt a robustly realist approach to value, meaning that we should see value as an “objective” feature of some parts of our world.

I suspect most readers will react to this in one of two ways. Either they’ll intuitively be skeptical, because they see value as subjective, or they’ll agree that value is objective because they hold some sort of religious beliefs where a deity supplies the foundation for objective value. I was taught the first version growing up, so I’ll mostly speak to that perspective here. On the first view, valuing occurs when my mind experiences a value neutral physical world and then applies value to things based on my preferences, like a painter applying color to a blank canvas.

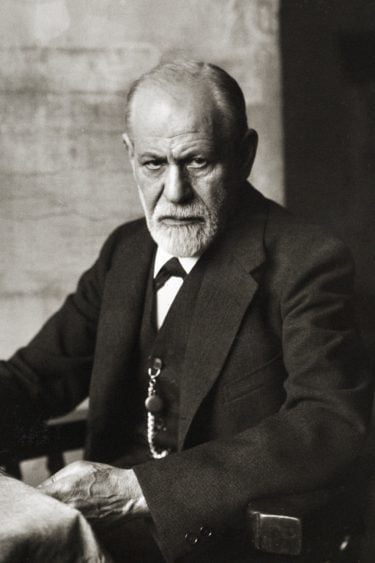

This view of value, which is commonly attributed to David Hume, fits comfortably with the common understanding of scientific truth. It generates an intuitively appealing divide between facts and values. Factual claims are claims about the world itself, and so can be true or false. Evaluative claims are about our feelings and preferences towards the world, and so are neither true nor false. Value is merely a sophisticated mental construct, rather than some objective feature out there in reality, like the spin on an electron or the almond in a chocolate bar.

In the area of ethics, Hume presented perhaps the most famous version of the fact/value divide, what’s known as the ‘is/ought divide’ or the ‘is/ought problem’. It is one of the most hotly contested pieces of real estate in all of philosophy:

In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surprised to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation, it’s necessary that it should be observed and explained; and at the same time that a reason should be given, for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it. But as authors do not commonly use this precaution, I shall presume to recommend it to the readers; and am persuaded, that this small attention would subvert all the vulgar systems of morality, and let us see, that the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason.

The most common reading of this passage is that you can never derive an ‘ought’ claim from an ‘is’ claim, such as inferring from “this object is a gun” to “this object is immoral”. In order to justify the claim that guns are immoral, we need some evaluative premise like “all objects that are highly deadly are immoral”, but the problem then arises where we find justification for that claim, and so on into infinity. Combine this problem with the value neutral model of the world, and it would seem that there is no way to ground “ought” claims. This is why the view commonly entails that moral claims and other evaluative claims either can’t be true or false, or are simply all false, because there is no way to ground them. At this point, the risk of nihilism, the rejection of all valuing, looms large, and the project of fields like metaethics and value theory becomes about salvaging a social basis for grounding moral claims, or at least some pretext for continuing to talk about them.

It’s debatable how much Hume actually held an antirealist view about value, and there are several incompatible interpretations of his famous is/ought problem. Realists like myself will point to Hume’s claims that there are proper objects of valuing and that our moral sense can be improved with training as evidence Hume also believed in something like objective value. Still, the dominant successors to Hume, especially the Emotivists, carried forward the distinctions Hume made, with the result that many today take for granted that we live in a value neutral world and make evaluative judgments about it based purely on subjective preferences.

Several concerns arise with a view like this. One major concern, often voiced by religious conservatives, is that widespread adoption of the Humean view has contributed to the crisis of meaning that many are experiencing in the modern world. The rejection of the previous structure of meaning, one where a god or some other outside force imbues your life with purpose, created a vacuum in many people’s worldviews that remains to be filled, leading to a slide into hedonistic cultural decadence. Schools of thought like Existentialism arose in an attempt to address this absurdity of desiring meaning in an uncaring universe, with mixed results. To avoid nihilism, many of us can get caught up on the hedonic treadmill, where we always seem to need more and more to be satisfied, whether it’s pleasure or some fleeting sense of purpose. The result may be a turn to conspiracy theories and other narratives that return some sense of cosmic purpose.

Similarly, abandoning objective value means abandoning objective morality and the idea that some things are right or wrong whether or not we think they’re right or wrong. Much of the work of metaethics in ancient philosophy and over the past few hundred years has centered on challenges to objective moral truth and attempts to either refute those challenges or construct a subjective system of ethics that can serve as an adequate replacement. For example, moral constructivists argue that we can create reasoning procedures that are suitably fair such that no person could reasonably reject the conclusions of that procedure, conclusions like society must protect everyone’s rights equally. Critiques argue though that constructivist models fail to reach substantive moral conclusions without smuggling them in through implicit premises, which is actually the problem I think Hume was trying to highlight when he first proposed the is/ought divide. So, what do we do if subjective theories of value seem insufficient but we don’t want to abandon valuing entirely? I think the takeaway is to grow skeptical of how we’ve divided the world, and to question how that framing has lead us astray. I lack the space or the insights to provide a complete alternative, but let me point in some directions I hope are helpful.

First, I think it’s valuable to remember that the universe doesn’t just contain value neutral particles smashing into each other, even if that’s what everything ultimately is composed of. The world contains emergent phenomena, meaning entities that seem to have properties distinct from, and not reducible to, the properties of the particles or whatever that make them up. Your mind, with its internal states of awareness that are only perceptible to you, is a classic example of an emergent phenomenon, and much work has been done on the “hard problem” of trying to explain how minds could emerge from matter. What’s important here is that mind and matter, whatever their relationship, are both “part of the world”. They’re both things about which claims can be objectively true or false.

I worry that describing our minds as “part of the world” can feel jarring to some folks, because they have so internalised the separation between “the world out there” and the space we call “inside us”. It’s understandable, the distinction is intuitive and it has the benefit of quarantining minds, with all their messiness, away from the rest of reality which we can effectively study with our “hard” sciences. Unfortunately, dividing the world this way obscures more than it clarifies.

For example, and painfully abbreviated, suffering is a value-laden state that we all experience directly at many points in our lives. Your access to the suffering is fundamentally subjective, but the fact that you are suffering or not is a claim about the part of the world that is you, and its truth or falsity can be independent of anyone’s beliefs about it. Perhaps you live in a society so oppressive it has fully convinced you that your suffering is really flourishing; it would remain an objective fact that you are suffering.

Furthermore, it is a necessary feature of that suffering that it has some negative value, even if that negative value is outweighed by some other gain. Some suffering may be justified, but all other things being equal suffering is bad and instils in us an obligation by its very existence. The negative value of suffering does not fit the antirealist model of us applying negative value to a value neutral state of the world. Rather the negative value is a feature of the suffering, which is a part of the world, and our perceptions of that suffering and other value-laden states like flourishing give us access to objective moral and evaluative truths. On this view, which I find more intuitive than the antirealist model, it wouldn’t make sense for you to say “I’m suffering, but I’m not sure if there’s anything bad about it or not” or “that person is suffering, but it’s unclear if that matters”.

Therefore, at least one corner of the universe, the one that contains things like your suffering and your flourishing, has parts of it that exist objectively and are objectively value-laden. Attempt by earlier thinkers to exclude minds from the world was appealing, given the difficulties with studying minds scientifically, but it led us astray on this basic fact, and it’s time we find our way back. I believe the upshots are that our lives are filled with robust moral obligations but also with an overabundance of meaning and value. It may be hard to feel it sometimes. We may lose our way and society may twist us to value the wrong things or to value the right things to excess, but there are still things in the world worth valuing, and we’re some of them.