English is a wonderfully flexible language, and modern lexicographers tend towards descriptivism rather than trying to stem the tide of new meanings. Definitions change with usage, with one most notable example being “literally”, which in English dictionaries has both the original meaning, and also the sense often employed today, in which literally is used to mean “virtually” or “metaphorically”. While it upsets Daily Mail comment pedants, this is how English has always worked; if a term is widely used to mean something, then that’s what it means.

Which brings us to a different group of pedants: skeptics. I confess that I have railed against the use of certain terms being used incorrectly – and suspect many readers have too. Where should we stand our semantic ground, and where are we trying to close the linguistic barn door after the horse has bolted?

‘UFOs’

- What some more pedantic skeptics think it means: unidentified objects that are, you know, flying.

- What everyone else thinks it means: alien spaceships

I hear UFO and think that the speaker means an object that’s flying and hasn’t been specifically identified. Unfortunately, the rest of the world thinks of alien spaceships, to the point that the Cambridge Dictionary definition is:

an object seen in the sky that is thought to be a spacecraft from another planet

While Merriam Webster is a little more cautious:

a mysterious flying object in the sky that is sometimes assumed to be a spaceship from another planet

UFOs are currently a more lively area of discussion than they have been for years, as the US government has released a lot of UFO reports and footage – which is to say, footage of aerial phenomena that have not been identified.

The reports make it very clear that they believe some reports to be “sensor errors, spoofing, or observer misperception” and that others may be “technologies deployed by China, Russia, another nation, or non-governmental entity”, rather than presuming aliens, though that explanation isn’t ruled out. Someone in the US government has been thinking hard about this very issue, referring to UAP – unexplained aerial phenomena – rather than UFOs, presumably in an effort to avoid the assumptions and stigma associated with the term. Those efforts are laudable and maybe an approach for us to consider pursuing, but for now everyone from The Economist to The New York Times still goes with the term UFO in their headlines.

It seems to me that we skeptical pedants have already lost this one.

‘Chiropractors’ (also: ‘Osteopaths’)

- What skeptics think it means: Pseudoscientific practitioners of unproven and broadly ineffective treatments that use spinal manipulation.

- What

everyone elsea lot of other people think it means: back doctors.

This was one of several early entry points for me to the world of skepticism. A ridiculously tall chap, I was prone to joint and back pain even in my relative youth. On one visit to the doctor I mused out loud that maybe what I needed was to be referred to a chiropractor or osteopath. The GP almost physically recoiled from me and assured me that while physiotherapy might be required, an osteopath or chiropractor most certainly was not. Your curious young author went home and spent a good amount of time on the internet untangling the difference.

Like a good portion of the general public, I had mistakenly thought that chiropractor simply referred to specialist back doctors, when of course chiropractic is based on the idea that vertebral misalignment is responsible for all manner of health conditions, and can be cured through spinal manipulation. Of course studies have failed to show that it is an effective treatment for any condition, although there may be some evidence for use in certain back conditions.

Osteopathy is a little different, with osteopathy now increasingly merging in the USA with mainstream medicine, but the origin of osteopathy is found in pseudoscientific roots rather like chiropractic, with its founder Andrew Still claiming that he could “shake a child and stop scarlet fever, croup, diphtheria, and cure whooping cough in three days by a wring of its neck.” Yikes.

This one isn’t over, and as skeptics we should at least try to stem the tide here. If you have muscle pain, you need a physiotherapist. If you somehow missed your vaccines as a baby and have diphtheria then you need to seek urgent medical attention and antibiotics, not to be shaken or have your spine manipulated.

This distinction is well worth maintaining.

‘Placebo’ / ‘Placebo Effect’

- What some GPs and doctors mean: placebos are something innocuous that you know won’t help, given to make a patient feel better temporarily, and to get the patient off your back in the process.

- What some scientists and skeptics mean: patients in the placebo arm of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to test the efficacy of a drug will be given an inert substance that looks, tastes and seems a lot like the actual treatment. The placebo effect refers to all the factors beyond the study’s control – regression to the mean, subjective improvements, other researcher errors, and so forth.

- What some other skeptics, medics and scientists mean: innocuous placebo treatments create an effect, presumably caused by some hitherto unknown mechanism, that not only creates subjective improvements, but somehow also objective improvements.

- What everyone else thinks: Everyone else is confused, and who can blame them when they have different qualified groups sending them such mixed messages.

Clinical researchers have known since the introduction of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that the placebo effect was describing the bias, error, illusory effects, conditioning, and subjective improvements that they needed to account for when testing the efficacy of a new drug. The whole point of placebos, a term much older than the RCT, is that they provide an innocuous soothing result in a patient, but that they don’t do anything.

Somehow along the way (and discussed in detail by Mike Hall in more than a few episodes of the Skeptics with a K podcast) other scientists, researchers and even skeptics misunderstood this and started assuming that placebos were having real effects that could create actual, objective improvements in medical conditions, including, most famously, Dr Ben Goldacre:

The placebo effect, similarly, can mislead us all: people really can get better, in some cases, simply from taking a dummy pill with no active ingredients, and by believing their treatments to be effective.

This is not the case, however. It has been found that the effect of placebo on the patient is subjective rather than objective. Patients given sugar pills feel better, but they are not actually objectively any better.

This is one of those times when both UK and US dictionaries have this down entirely correctly, and it is incumbent upon skeptics to educate ourselves and others, because purveyors of pseudosciences such as acupuncture are already using the “powerful placebo” myth to justify their nonsense.

‘Risk’ (increased / reduced)

- What scientists often mean: the measured increase or decrease in the probability of a specific thing happening when you change a variable, compared to baseline for the situation.

- What almost everyone hears: if I do this thing I will be safe / If I do this thing I will be in terrible danger.

Apples fight cancer (and heart disease, and strokes) says The Daily Mail, an organ renowned for its apparent mission to decide whether everything either cures or causes cancer:

The latest pioneering research in America has revealed that drinking apple juice and eating apples can reduce the risk of heart disease.

As obsessive as the Daily Mail is on this subject, many other news organisations also report on this sort of thing, with one recent prominent example being the finding that consuming bacon and other processed meats:

can significantly raise the risk of bowel cancer, one of the deadliest forms of the disease.

The word I’m picking on here is risk (though I could have picked on significant) and the inability of newspapers remember to include the word “relative” when appropriate. Statistics are complicated, but I am sure that the average mid-market tabloid reader can cope with the following, as explained by JV Chamary:

Many people will interpret “increases the risk of colorectal cancer by 18%” to mean a rise from zero to 18%. But that increase isn’t absolute risk – it’s the relative risk.

To put the figure in perspective: the risk of developing lung cancer is 23.6 times higher among male smokers than non-smokers, so smoking increases the relative risk by 2360%. So if you started with a hypothetical 5% risk of developing bowel cancer, consuming 50g of bacon every day would only raise your risk to almost 6%.

This detail was in the original research, of course, but it is absent from some of the coverage and only alluded to indirectly in the other coverage.

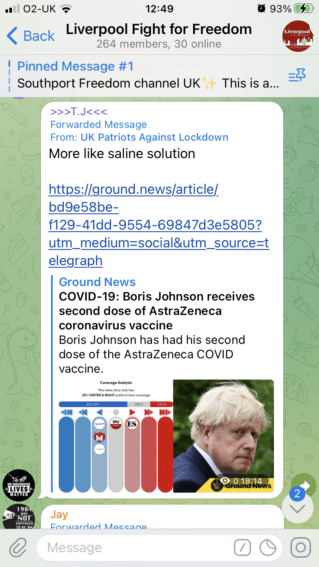

Does it matter? We all know a balanced diet and minimising comparatively unhealthy foods like bacon is for the best, but in the middle of a global pandemic, understanding risk in a more nuanced way is more important than ever. As vaccine take-up slows in the UK we have probably all spoken with friends and family hesitant to be vaccinated, as they are concerned about the risks of the vaccine, even though (comparing like with like) COVID-19 is a greater risk in all adult groups compared to the Pfizer vaccine, and all age groups over 30s for the AstraZeneca vaccine.

I know that bold statements in headlines sell papers and attract eyeballs, but if people misunderstand the risk of being vaccinated (after all, it is not risk-free) compared to the risk of COVID-19, then unfortunately people could die.

‘Theory’

- What scientists and skeptics mean: a systematic or scientific explanation for something.

- What everyone else means: a belief used as a basis for action; or conjecture, or speculation.

This is a source of enormous frustration for anyone arguing with creationists, who are known to insist that the theory of evolution is “only a theory”. Evolution by natural selection is a theory, of course – and it is fact! – but this argument relies partly on the lay use of the word theory, which does literally mean speculation, at least in one common usage, and has done since the late 16th century, some decades before it was used in a more scientific context.

There’s very little that can be done about this, except to be aware of the divergence in meaning in a lay and scientific context, and to remember that if you’re arguing with a creationist online you’re probably not going to convince them anyway.

‘Critical thinking’

- What most skeptics and educators mean: analysing facts carefully to come to a reasoned judgement.

- What other skeptics mean: I’m a critical thinker and can point out logical flaws in arguments, so I’m always right.

- What some other people assume is meant: criticising.

Obviously critical thinking and criticism are different, but it isn’t helpful that some dictionaries, including Merriam Webster, don’t even attempt to define this one.

University websites are rather more useful, and I think that Stanford has it down pretty well:

Its definition is contested, but the competing definitions can be understood as differing conceptions of the same basic concept: careful thinking directed to a goal… “Critical thinkers” have the dispositions and abilities that lead them to think critically when appropriate… Controversies have arisen over the generalizability of critical thinking across domains, over alleged bias in critical thinking theories and instruction, and over the relationship of critical thinking to other types of thinking. [emphasis mine]

I’ve spoken with lecturers whose students embrace critical thinking a little too wholeheartedly, believing that they should question every single fact they’re taught to an unmanageable degree, but as a rule, higher education is all about critical thinking and professors welcome students who are critical thinkers – especially those who are willing to apply the methods to their own claims.

Skeptics also like to think that we’re critical thinkers, but I do sometimes wonder if we, too, embrace the critical a little too readily, and assume that just because we can spot a logical fallacy that we must be right, our opponent is stupid and victory is assured. Don’t forget that the average conspiracy theorist believes they’re just as rational, reflective and unbiased in their thinking as the next person, even if they actually score badly as critical thinkers!

I think that the best way for critical thinking to be more widely understood is to use it (appropriately), fly the flag for it (when appropriate), and don’t be a jerk (unless appropriate!).

![Hoa Hakananai'a standing in the British Museum. Image by Wikimedia user Fallschirmjäger [CC BY 3.0].](https://www.skeptic.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Hoa_hakananai-343x567.jpg)