Conspiracy theories are having a moment right now, there’s no denying that. Five years ago, the notion that the earth was flat was the pet theory du jour of “independent thinkers”, and when that particular movement lost momentum, QAnon rose up to take its place. When the pandemic came along – coinciding with a conspiracist-in-chief in the White House – conspiracy theories went truly mainstream. They’ve been a primary focus of this magazine ever since my first article after taking over as editor, and they are unquestionably a threat, to some degree, to social cohesion in almost every part of the world.

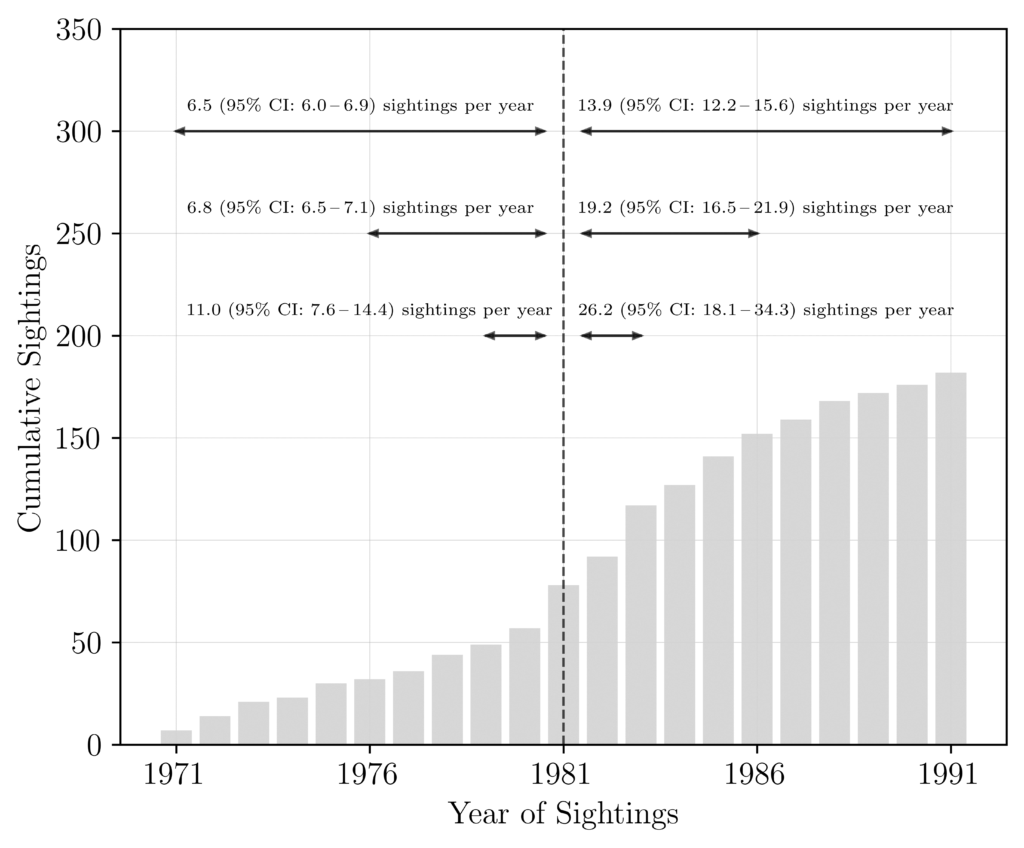

As someone who spends far too much of his time looking for the next conspiracy theory – and the next prominent promoter of the theory, so I can secure an interview – it has certainly felt to me like there has been a noted uptick in the prevalence of conspiratorial thinking. But how big of a problem actually is it, and how many people are drawn into these paranoid and demonstrably false beliefs?

Answers to these questions came in the form of a report this week, which suggested that conspiratorial thinking is widespread and wildly out of hand. As the Guardian’s coverage explained:

Quarter in UK believe Covid was a hoax, poll on conspiracy theories finds

The UK is home to millions more conspiracy theorists than most people realise, with almost a quarter of the population believing Covid-19 was probably or definitely a hoax, polling has revealed.

This is obviously a striking finding – the UK has a population of almost 70 million people, so a quarter of that is a staggering number of people. Even if we discount children, we’d still be looking at the best part of 12 million people in the UK who don’t believe that the pandemic was real.

It gets worse, too, because the conspiracism is not merely around the pandemic:

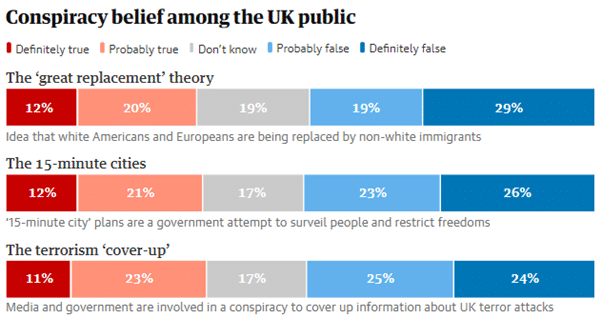

About a third of the population are convinced that the cost of living crisis is a government plot to control the public, and similar numbers think “15-minute cities” – an attempt to increase walking in neighbourhoods – are a government surveillance ruse, and that the “great replacement theory” – the idea that white people are being replaced by non-white immigrants – is happening.

If anything, this is an even more concerning finding than the last; the great replacement theory (otherwise known as the Kalergi plan, as discussed in depth elsewhere on The Skeptic) is an explicitly white supremacist and antisemitic notion, which posits that a shadowy cabal of “elites” (read: Jews) are deliberately driving mass immigration into nations like the UK and US, in order to flood the country with people of colour, thus diminishing the power, purity and bloodlines of the white race. For more than 15 million adults in the UK to believe in this idea – and, according to the chart released alongside the data, for 12% of Britons to think this is “definitely true” – would be deeply worrying.

The results came from a survey conducted by Savanta and commissioned by The Policy Institute and the BBC, in which 2,274 adults were asked a series of questions about their conspiratorial beliefs. Those numbers were then weighted so as to be representative, and extrapolated into these incredibly attention-grabbing headlines.

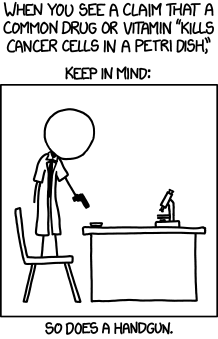

However, before we accept these findings at face value, and begin decrying the widespread death of critical thinking and basic humanity, it’s worth asking: do these findings actually make sense?

Take, for example, the quarter of people who said they believed Covid was a hoax. How does that finding fit with the fact that, according to the ONS, 93.6% of people aged 12 or older had received at least one dose of vaccination against Covid, and 88.2% got their second dose. These numbers were from August 2022, so the rates are likely to be even higher than that.

For both of these sets of figures to be simultaneously true, there would need to be huge numbers of people who thought that Covid was merely a hoax perpetrated by the UK government, who still allowed that same government to give them two doses of the vaccine that they believed to be dangerous. Something here just doesn’t seem right.

Similarly, the strength of feeling about the notion of 15-minute cities seems deeply unlikely: I wrote about the 15-minute city panic in March, just one month before Savanta conducted their research. In the article, I spent some time explaining what the concept of a 15-minute city actually is, because at the time, nobody I spoke to seemed to have heard of it. Yet, one month later when this survey was conducted, 12% of people thought it “Definitely true” and 21% thought it “probably true” that it was a government plot to surveil people and restrict our freedoms. How did this idea go from obscurity to something that 33% of all adults were certain was a tool of totalitarian control?

There are a number of possible explanations. One option is that the people I was speaking with happened to be among the 17% of people who would go on to say “don’t know” in the survey. Another is that, in the time between March 10th and April 28th, the awareness of 15-minute cities skyrocketed – it’s possible, though from a glance at the analytics for my article, it seems unlikely that the subject matter suddenly got picked up by the Zeitgeist. Or the third option is that there were flaws, errors, noise or statistical weirdness in Savanta’s survey data, that renders it of relatively little use for extrapolating up to a population level. Call me a skeptic, but that third option feels by far the most parsimonious.

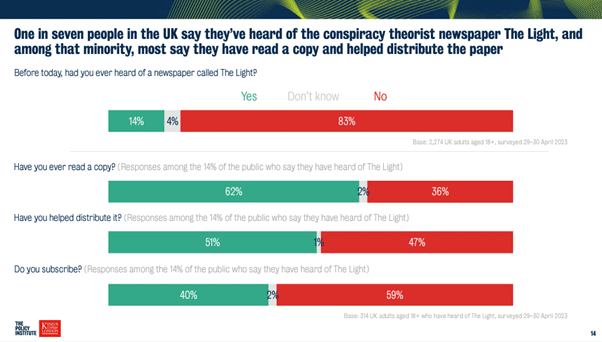

There are other clues that suggest this data may not be usefully reflective of the whole UK population. In the summary put together by Savanta, they summarise that one in seven people in the UK have heard of The Light paper, an anti-vax, conspiracy heavy, freely-distributed newspaper that emerged during the pandemic. Of those who have heard of it, 51% of people help distribute it and 40% subscribe to it (by which I assume they mean make donations to keep the paper operational).

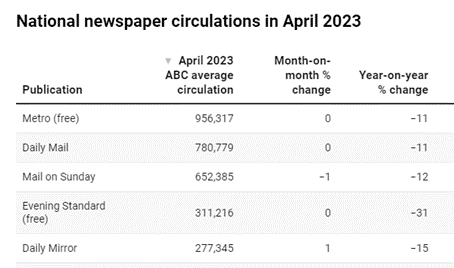

These numbers seem extraordinary – this would give The Light a reach of 6.7m people, of whom 4m are readers, and 3.4m take time out to volunteer to distribute it. If “subscribing” means donating as little as £1 per month, these figures would give The Light an income of £32.25m annually – more than the Daily Telegraph (OK, possibly a bad example).

Is it possible that this free antivaxx newspaper is actually such a powerhouse of publishing? Again, familiarity with the subject matter allows for a reasonable sense-check. Mark Horne covered The Light paper for this magazine in April 2022 – it is handed out by the White Rose antivaccination movement, and by activists from Stand in the Park, and it was founded by Darren Smith/Nesbitt, formerly one of the UK’s most prominent flat earth proponents. Darren, by odd happenstance, is someone I know: I saw him speak at the flat earth conference in 2018, and interviewed him later that year to talk about his flat earth beliefs; I then interviewed him again in February 2021 to talk to about Covid and The Light paper. I have been in the Telegram group for The Light paper since 2021 – it currently has 19,955 subscribers there (fortunately, the recent publicity it has received has not substantially increased that number – according to one of the channel’s moderators, the spotlight put on it by the BBC resulted in only around 50 new subscribers).

When you spend any amount of time researching and understanding The Light paper, it becomes abundantly clear that it cannot possibly be true that millions of people volunteer to distribute it, nor that it makes seven-figure profits and has a circulation four times larger than the Metro and five times larger than the Daily Mail.

So if these findings fail a basic sense-check, what might be going on to give these extraordinary and headline-making results? There’s a few possible explanations, some of which are outlined by Stuart Ritchie in the i-newspaper – such as the possibility that respondents had a wide range of interpretations of quite what is meant by a “hoax” in relation to Covid. There’s also the fact that a certain number of respondents will give unexpected and untrue answers in surveys – either because they want to please the interviewer by telling them what they think they want to hear, or because they want to appear more knowledgeable than they are and thus will report having heard of something they haven’t, or because they want to disrupt the survey as a bit of fun.

There’s also the issue of representativeness – survey methodologies vary quite wildly, but even surveys that are sampled and weighted to try to be as representative as possible can still get it wrong. This is especially the case once the data starts getting segmented out – like the analysis of the number of people who distributed The Light paper, which was a subset of the 14% of people who say they’d heard of the The Light paper. Once data is split and then split again, it’s incredibly hard to maintain that representativeness, and anomalies can slip in – which is fine, that’s part of the art and science of polling, but it has to be accounted for, especially if the poll throws up wildly unlikely findings.

As Anthony Wells, Head of European Political and Social Research at YouGov UK, wrote in reaction to the story:

Often, the most eye-catching and surprising results are the ones most likely to be suspect – they’re surprising for a reason, after all. One way to avoid falling victim to over-hyping an anomaly is to do the kind of basic sense-checks I’ve tried to do here. Another way is to check the results against other findings – like, for example, YouGov’s 2021 poll, which found that 3% of Britons agreed that COVID-19 was a hoax. Or perhaps to turn to the academic literature, where a 2022 study published by Uscinski et al found that, contrary to popular wisdom (and, I’ll be honest, my own gut feeling), there is scant evidence for a rise in conspiracy theory across the world.

None of this, of course, is to say that conspiracy theory is not a problem, nor that The Light paper is not worthy of concern; as someone who regularly speaks with conspiracy theory proponents, and who as spent the last few years watching The Light move from misreporting Yellow Card data on vaccine side effects to directly sharing white supremacist Great Replacement messages in their Telegram, I do believe we should be paying attention to the radicalisation pipeline that conspiracism offers. But for us to deal with the problem effectively, we need to have a genuine understanding of the scale of it, and over-stated and obviously implausible headlines claiming a third of the country are conspiracy theorists does nothing to further that cause.