Lake Champlain is a large lake spanning two US states and one Canadian province, with a maximum depth of 122 meters, and a surface area of over 1,000 square kilometers (Myer, 1979). Not unlike Loch Ness in Scotland, an unknown aquatic animal is alleged by some to inhabit Lake Champlain, variously dubbed ‘The Lake Champlain Monster,’ ‘Champy,’ ‘Champ,’ and the trinomen Belua Aquatica Champlainiensis (a nomen nudum, as there is no formal diagnosis differentiating it from other taxa). Champy has been speculatively identified as outdated reconstructions of such extinct forms as plesiosaurs and archaeocetes (Earley, 1985; Mackal, 1983, Chapter XI).

Perhaps the strongest evidence presented to support the existence of an unknown animal in Lake Champlain is the 1977 ‘Mansi’ photograph, which depicts a dark shape above the lake surface resembling a longnecked marine reptile. Apparently, the picture was not tampered with in any way, but may feature a sand bar upon which a model could have been placed (Frieden, 1984). LeBlond (1982) used the Beaufort scale to estimate the wind speed and wavelength in the photograph, and from these estimated the size of the subject at 4.8 to 17.2 meters. Field experiments have reduced this estimate to 2.1 meters (Radford, 2003) or 1.3 meters (Raynor, 2015). Whatever the size, it has been suggested that the publication of the Mansi photograph may have led to an increase in the number of sightings at the lake due to ‘expectant attention’; the tendency for observers to ‘see’ what they anticipate they will see (Radford and Nickell, 2006, Chapter 2). Evidence for expectant attention in the Lake Champlain context may come from statistical analysis of Champ ‘sightings’.

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, the Lake Champlain Phenomena Investigation (LCPI) and associated organisations attempted to collect further evidence with sonar, shoreline and vessel surface surveillance, scuba dives, hydrophones, and a remotely-operated submersible (Deuel and Hall, 1992; Smith, 1984, 1985; Zarzynski, 1982, 1983, 1984b, 1985, 1986b, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990). Hundreds of eyewitness testimonies were collected, as well as a dozen or so ambiguous sonar contacts, but no definitive autoptical evidence was obtained.

In the absence of physical material, purported sightings of unknown animals at Lake Champlain have been studied statistically. In a previously-published analysis, Kojo (1991) reported that Champ sightings most frequently occur just before sunset, in contrast to how most lake visits occur earlier in the day. Kojo interprets this as evidence for the existence of nocturnal unknown animals. However, qualitative descriptions of sightings times such as “late afternoon,” “dusk,” and “about midnight” were excluded, which has the potential to bias the analysis. Thus, a reanalysis including these data is warranted to determine how robust that conclusion is.

The previous analysis reported that the majority of sightings with descriptions of locomotion describe vertical undulation of the body, but did not emphasise how few sightings included any description of locomotion, nor how many sightings were missing data in general.

Finally, data on other aspects of sightings – such as the diversity of morphological descriptions, the distance to the object, estimates of its size, and whether distance and size are associated in a statistically significant way – were not reported in the previous analysis.

Given all of the above, I undertook a study to re-analyse over 300 Champ ‘sightings’ with statistical methods, including sightings which were not previously analysed. Methodological details are available in a technical report online along with the data and code used in the analyses.

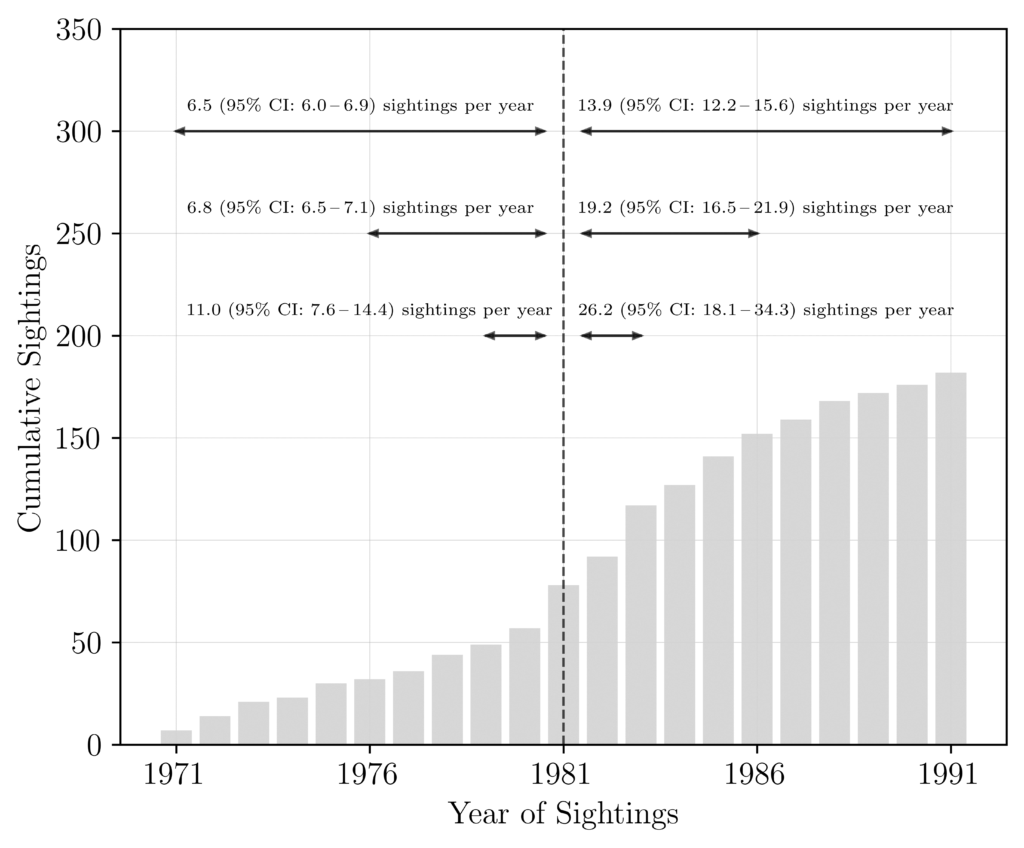

Figure 1 shows the cumulative number of purported sightings of unknown animals at Lake Champlain across the period of time ±10 years around the 1977 Mansi photograph (published in 1981). As detailed in the figure, numbers of sightings per year were over twice as great in the periods 2, 5, and 10 years after the publication of the Mansi photograph in 1981, compared to the periods 2, 5, and 10 years before publication. The increase in number of sightings per year after the Mansi photograph diminished around 1987/8 when sightings per year returned to pre-Mansi levels.

This finding, that the rate of sightings increased significantly after the publication of the Mansi photograph, may be interpreted by a cryptozoologist as evidence of publicity driving more cryptid-seekers to Lake Champlain, and therefore more sightings being made (since the number of sightings is a function of the number of visitors). A skeptic may interpret the same finding as evidence of expectant attention; after seeing the Mansi photograph, lake-goers may be more likely to think they have seen Champ because that is what they have anticipated they will see.

The conditions under which sightings were made were largely consistent; the majority of sightings occurred in Summer (70.1%) under calm lake surface conditions (83.9%), between Noon and Evening (73.9%), and were made by more than one witness (72.9%). A cryptozoologist may interpret the consistency of sighting conditions as evidence of consistent behavioural characteristics among Champ animals, while a skeptic may interpret this consistency as evidence of regularity of wind/wave effects (Bauer, 1992), sampling error or other bias, and/or characteristics not of the Champ animals but of the observers (Mackal, 1992).

Indeed, in the case of the cryptozoologically-related coelacanth, catch data describes more about the habits of Comoran fisherman than about the fish (Thomson, 1992, Chapter 6). For example, Kojo (1991) suggested that most Champ sightings occuring in Summer is evidence of seasonal heterothermy, but this may also be explained by seasonal tourism in and around Lake Champlain.

Descriptions of the characteristics of the animal observed are much less consistent. Just 27% of witnesses described the appearance of the animal they had purportedly seen. Among those reports with appearance descriptions, the largest category (serpentine) consistent of just 36.5% of sightings, with the next largest specific categories being reptilian (15.3%) and marine mammal (11.8%).

Over 68% of sightings were missing data on one or more of appearance, motion, speed, height above the lake surface, and the number of humps, loops, coils, or portions seen. The characteristic with the most agreement was integument; 98.2% of sightings with data for integument described the animal as dark, which is unsurprising in a lake setting.

Thus, despite the claim that Champ has been seen by hundreds of eyewitnesses, detailed eyewitness descriptions of these alleged animals are few and disparate. Most sightings are missing data pertaining to morphological description, and those with data describe very different-looking objects; Champ sightings are not nearly as consistent as claimed by some (Radford and Nickell, 2006, Chapter 2). That a large proportion (27.4%) of sightings were described as appearing like logs, land mammals, birds, fish, and boats is logical because all of these are present at Lake Champlain. For example, in 1987 the LCPI observed deer swimming across the lake. Unknown animals are therefore unnecessary to explain many sightings. Sightings that occurred in late evening with low visibility are perhaps explained by observers being more likely to confuse ordinary phenomena with Champ in low light conditions.

The reported length of objects sighted in the lake varied massively from less than one meter to nearly 60 meters, with an average of 6.6 meters and the median was 6.9 meters. The average reported distance between the observer and the object sighted was 247.2 meters, with a median of 91.4 meters. When outliers were excluded, there were no statistically significant correlations between any of reported length, reported height, and distance to the object sighted. The most parsimonious explanation for these non-associations is that eyewitnesses over- or underestimate distance and size, or have witnessed entirely different events occurring in the lake.

In conclusion, if not a fake, what’s in the lake may be ordinary phenomena innocently mistaken for unknown animals, in part driven by expectant attention and the publicity of the Mansi photograph. Alternatively, Lake Champlain is inhabited by multi-humped, dark-coloured serpents approximately seven meters in length, which locomote in a fast and sinuous fashion, and which prefer pleasant Summer afternoons and evenings, as well as appearing before crowds. Deciding which explanation best accounts for the data is left as an exercise for the reader.

Regardless, Champ research and advocacy has apparently advantaged the local people and animals; in 1986, the Vermont Senate followed the New York Senate in adopting the “Champ Resolution,” calling for the protection of possible unknown animals in the lake, which likely benefited the known lake fauna. Systematic searches at Lake Champlain have also enabled the discovery of many archaeological artefacts (Zarzynski, 1986a) such as the shipwreck of the tugboat William McAllister, which was discovered off Schuyler Island during a six-day search of the lake bed designated ‘Project Champ Carcass’ (Zarzynski, 1987). Each year since 1985, the Moriah Chamber of Commerce has hosted the annual Champ Day: Lake Champlain Monster Festival, which undoubtedly supports local businesses with the crowds it brings to the lake.

Many thanks to paleontologist Tyler Greenfield, who highlighted that the original “binomen Beluaaquatica champlainiensis” should actually read “trinomen Belua Aquatica Champlainiensis“.

References

- Bauer HH (1992). Analysis of Sightings at Lake Champlain. Cryptozoology 11, 138–139.

- Deuel RA and DJ Hall (1992). Champ Quest at Lake Champlain, 1991-1992. Cryptozoology 11, 102–108.

- Earley GW (1985). Book Review: Mysterious America. Cryptozoology 4, 93–94.

- Frieden BR (1984). Interim report: Lake Champlain ‘monster’ photograph. In: Champ – Beyond the Legend. Ed. by Zarzynski JW. Port Henry, New York: Bannister Publications. Chap. Appendix 2.

- Kojo Y (1991). Some Ecological Notes on Reported Large, Unknown Animals in Lake Champlain. Cryptozoology10, 42–54.

- LeBlond PH (1982). An Estimate of the Dimensions of the Lake Champlain Monster from the Length of Adjacent Wind Waves in the Mansi Photograph. Cryptozoology 1, 54–61.

- Mackal RP(1983). Searching for Hidden Animals. Cadogan Books.

- Mackal RP (1992). Are Lake Monster Sighting Times Biologically or Culturally Based? Cryptozoology 12, 114.

- Myer GE (1979). Limnology of Lake Champlain. Vol. 30. Lake Champlain Basin Study, New England River Basins Commission.

- National Center for Health Statistics (2021). Measured average height, weight, and waist circumference for adults aged 20 and over. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/body-measurements.htm.

- Radford B (2003). The Measure of a Monster. Skeptical Inquirer 27.

- Radford B and J Nickell (2006). Lake Monster Mysteries: Investigating the World’s Most Elusive Creatures. University Press of Kentucky.

- Raynor D (2015). A Study of the Mansi Photograph taken at Lake Champlain. https://www.academia.edu/11573500/A_Study_of_the_Mansi_Photograph_taken_at_Lake_Champlain.

- Smith RD (1984). Testing an Underwater Video System at Lake Champlain. Cryptozoology 3, 89–93.

- Smith RD (1985). Investigations in the Lake Champlain Basin, 1985. Cryptozoology 4, 74–79.

- Thomson KS (1992). Living fossil: the Story of the Coelacanth. WW Norton & Company.

- Zarzynski JW (1986a). Monster Wrecks of Loch Ness and Lake Champlain. MZ Information.

- Zarzynski JW (1982). LCPI Work at Lake Champlain: 1982. Cryptozoology 1, 73–77.

- Zarzynski JW (1983). LCPI Work at Lake Champlain: 1983. Cryptozoology 2, 126–131.

- Zarzynski JW (1984a). Champ – Beyond the Legend. Port Henry, New York: Bannister Publications.

- Zarzynski JW (1984b). LCPI Work at Lake Champlain: 1984. Cryptozoology 3, 80–83.

- Zarzynski JW (1985). LCPI Work at Lake Champlain: 1985. Cryptozoology 4, 69–73.

- Zarzynski JW (1986b). LCPI Work at Lake Champlain: 1986. Cryptozoology 5, 77–80.

- Zarzynski JW (1987). LCPI Work at Lake Champlain: 1987. Cryptozoology 6, 71–77.

- Zarzynski JW (1988). LCPI Work at Lake Champlain: 1988. Cryptozoology 7, 70–77.

- Zarzynski JW (1989). LCPI Work at Lake Champlain: 1989. Cryptozoology 8, 67–72.

- Zarzynski JW (1990). LCPI Work at Lake Champlain: 1990. Cryptozoology 9, 79–81.