It all started with a curious mind and an innocent scroll through social media. Little did I know that within 15 minutes and two YouTube videos later, I’d be plunged into a world where ordinary people, indistinguishable from those we pass daily in supermarkets or at flower shops, were fervently texting until beyond midnight in Telegram groups. Their mission? Crowdfunding for a camera to capture celestial evidence to support their flat earth theory.

This was just the beginning. My TikTok For You page soon overflowed with conspiracy theories about body healing, while Instagram politics unfurled a new layer of hidden, dangerous ideologies.

In the digital age, marked by rapid technological advancement and unprecedented access to information, Generation Z stands at the forefront of a digital revolution. Growing up in a world immersed in social media, instantaneous communication, and a wealth of knowledge at their fingertips, this generation faces a unique challenge as they navigate the intricate terrain of the internet. While this era of digitisation has ushered in incredible opportunities and connectivity, it has also witnessed the alarming proliferation of conspiracy theories, misinformation, and disinformation across social media platforms.

The dangerous spread of conspiracy theories online is powerful, quietly moulding the thoughts and actions of a generation that’s always online. These theories, often lacking any factual basis, can have serious consequences, leading to the spread of fear, and even violence.

Conspiracy theories have almost certainly existed for as long as society has been around. During the Middle Ages, there were conspiracy theories claiming that Jews were causing plagues by poisoning well water. The upheavals and uncertainties in Europe after the Middle Ages led to further conspiracy theories, including the belief in a widespread network of witches and Satanic forces – put forth in the “Malleus Maleficarum”. The invention of the printing press and church sermons contributed to their dissemination, resulting in witch hunts that claimed thousands of lives.

In the 18th century, the target of conspiracy theories shifted in the United States from Jews to groups like the Freemasons, who were accused of plotting for power. In the 19th century, American Protestants feared being overrun by Catholics. Today, in modern Germany, the idea of being taken over by Muslims is promoted, with prominent figures like Eva Herman and right-wing politicians spreading such conspiracy theories. In the past, the Illuminati and Jews were accused of secretly controlling the world; today, the blame might equally fall on reptilian humanoids (though many would argue these are simply antisemitic notions in modern packaging).

Conspiracy theories on social media platforms can have real-world consequences, from stoking fear and anxiety to inciting violence and hatred. On TikTok, I’m bombarded with claims that the world is secretly ruled by a powerful, shadowy group. In a daily Instagram story, I was recommended to do a full moon ritual and load crystals, even though I don’t own any. Even in my day-to-day life, a friend excitedly shares an article about how horoscopes predict significant global events with spooky accuracy, and on the bus I overhear that all politicians are part of a grand scheme to mislead the public. It’s a bewildering collage of theories and claims, infiltrating seemingly every corner of my digital and social landscape.

I decided to delve deeper, by finding conspiracy groups to follow on Telegram. I knew that Telegram was popular with misinformation and conspiracy theory groups. I thought since this world was so hidden from me, it would be difficult to access, since generally, I believe if something is so off the wall, you would think it needs a lot to find and enter it. I was completely unaware of the extent of these groups, but I quickly realised, that once you know what you´re looking for, it is incredibly easy to join a group. You simply enter it. No need for requests or assumptions; with one click you become part of the community, and witness to their deep beliefs.

What I saw left me shocked: a world parallel to ours, with people convinced of the most absurd notions. I scrolled the chats, looking at pictures that tried to convince me that the earth is flat, and messages with three exclamation marks to send to friends and family to educate them and show them the truth about the leading news media of America hiding the truth about Joe Biden. But what I quickly realised too, it was a world of community and shared beliefs. Frustration quickly became apparent in every group, regardless of belief, they all had one thing in common: the conviction of knowing the truth and the frustration that people do not believe you. People who seem totally rational, except in this one area, are completely invested.

The spread of conspiracy theories is not a random occurrence; it relies on the human need for belonging and acceptance and is accelerated by the power of social media algorithms. With headlines such as “Biden Unveiled – Boris Johnson Whispers “You are not Joe Biden – Who the bloody hell are you” or “With Article 23, the private illegal German Bundestag was stripped of all economic areas on July 17, 1990. On October 3, 1990, Germany was officially changed to a fiction within the UN. Germany does not exist; it is a part of the USA”, the QAnon group tries to convince people on Telegram about the truth they believe in.

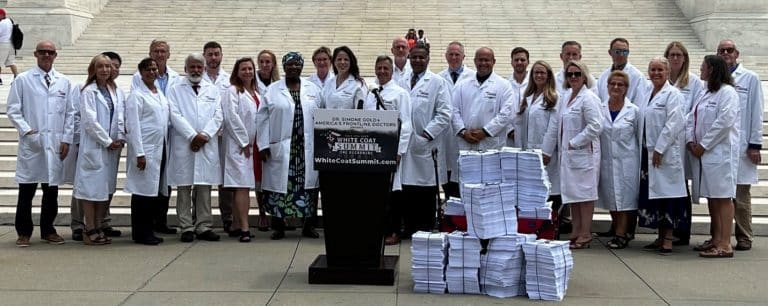

For example, consider how the “QAnon” conspiracy theory gained momentum by using cryptic messages. Misleading information, similar to how the false claim of 5G causing COVID-19, spread like wildfire. QAnon, a far-right conspiracy theory that surfaced in the U.S. in 2017, alleges a global plot against former President Trump by a cabal of Satan-worshipping paedophiles in high-ranking positions. Originating on internet forums, it gained traction through cryptic posts from an insider called “Q,” hinting at a battle led by Trump against this ‘deep state.’ Followers interpret these “Q-drops” to reveal supposed truths.

Despite its popularity, QAnon is widely discredited and criticised for promoting baseless, dangerous beliefs and has been linked to real-world violence. It has been debunked and faced bans on social media for inciting violence and spreading misinformation.

“QAnon is a phenomenon worthy of serious analysis, global tracking, and large-scale intervention,” according to Cynthia Miller-Idriss, professor at the School of Public Affairs and director of PERIL. “It is vital to draw attention to QAnon’s truly frightening potential for destabilization and permanent damage to our democratic system.”

Proponents offer simple explanations for complex problems, or appeal to people’s emotions, like the way anti-vaccine activists prey on parents’ fears about their children’s health. They promise to reveal the “truth” that the mainstream media won’t tell you, much like how climate change deniers suggest that scientific consensus is part of a global conspiracy. People do not choose what they believe based on a careful, rational evaluation of evidence; they often gravitate towards ideas that align with their preexisting worldview or respond to personal traumas and vulnerabilities. And with every like, share, and comment, these theories gain more traction, creating a snowball effect, as seen in how the false claims about COVID-19 vaccines went viral on social media. It’s a dangerous game, and we must all be aware of the tactics used by conspiracy theorists and do our part to stop them in their tracks.

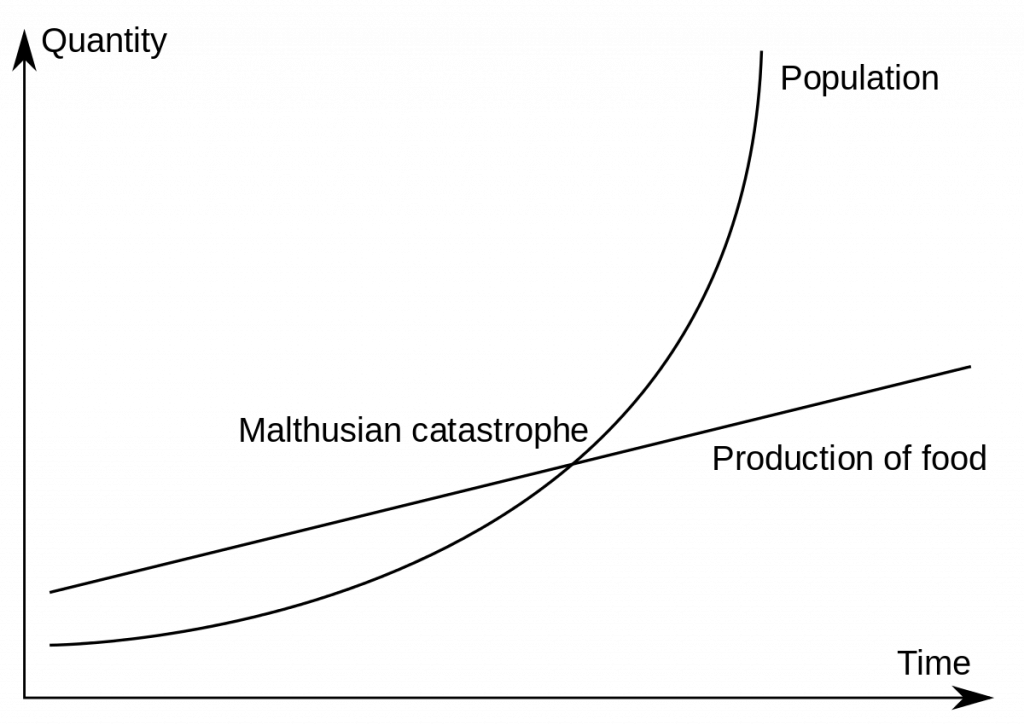

The global COVID-19 pandemic created a perfect storm for the proliferation of conspiracy theories, with lockdowns and uncertainty pushing many to seek explanations for the unexplainable. Conspiracy theories often emerge out of societal crises. People question why the pandemic happened, which results in anxiety and insecurity. Fears start to build, and it’s easier to seek out explanations for events that provide a sense of control or understanding. Conspiracy theories can offer a simple explanation for complex events, which can be appealing to individuals who are struggling to make sense of the world around them.

The hidden world of conspiracy theories on social media thrives, lurking beneath the surface, much like an iceberg with only a fraction visible. For many people, Google, YouTube, and Facebook represent the extent of their online universe, but beneath the surface lies a sprawling network of Telegram groups, message boards, and encrypted chat rooms where the wildest theories are cultivated and shared. Many people are unaware of these groups’ existence and the extent of their impact. These online communities serve as echo chambers, where like-minded individuals reinforce each other’s beliefs.

For individuals deeply invested in their beliefs, every event, no matter how small or coincidental, is often seen as a confirmation of their worldview. Take, for instance, the case of a nurse who experiences adverse effects from a Covid vaccine. To those already skeptical of vaccines, this becomes not just an unfortunate medical incident, but proof of their wider conspiracy theories.

This mindset, where everything is interpreted as happening for a reason aligned with one’s beliefs, is dangerous. It transforms normal life events into a conspiracy narrative. People start with wellness trends like yoga or crystals and gradually progress to more extreme beliefs, often propagated through YouTube and other platforms. Each step may seem insignificant, but over time, these small shifts accumulate, leading them far from their original standpoint without them realising the gradual change in their beliefs.

One of the key drivers behind the prevalence of conspiracy theories on social media is the algorithmic nature of these platforms. The goal of social media algorithms is to maximise user engagement and length of stay on the network. To achieve this, they often show content that aligns with a user’s existing beliefs and interests, creating a filter bubble that shields users from dissenting opinions.

But why should we care about this hidden world? Why should it matter to Gen Z and to society at large? The answer lies in the fact that this world, while hidden, is very real and poses significant dangers. The casual indifference with which many dismiss conspiracy theories can have grave consequences, as those we care about may fall victim to these ideologies. It’s not about dismissing people; it’s about understanding how misinformation spreads.

For instance, I spoke to Lisa, 24, who explained, “I came across Telegram groups which presented their ideas in such a compelling way that it was easy to get caught up in them. They used persuasive techniques, visuals, and confident narrators, which made their arguments seem convincing. When you’re alone in your room, watching these videos or scrolling through these groups, it’s easy to feel like you’re part of a community that knows something everyone else doesn’t.

“It wasn’t that I thought everyone around me was entirely wrong; it was more about feeling like I was uncovering hidden truths that others were oblivious to. The conspiracy theories presented an alternative narrative, often challenging the mainstream view, and it made me question whether I should trust traditional sources of information like parents, friends, or the media. It was the idea of being an independent thinker that pulled me in, but looking back, I see that it created a divide between me and those I cared about.”

The infiltration of conspiracy theories in Generation Z’s digital realm is not just an issue of misinformation; it’s a startling transformation of their reality, often leading them down a rabbit hole of shocking and potentially dangerous beliefs. This generation, constantly connected to a world of unfiltered information, encounters theories that aren’t just fringe ideas but are sometimes outlandish and extreme, yet presented in a way that’s alarmingly persuasive to young, impressionable minds.

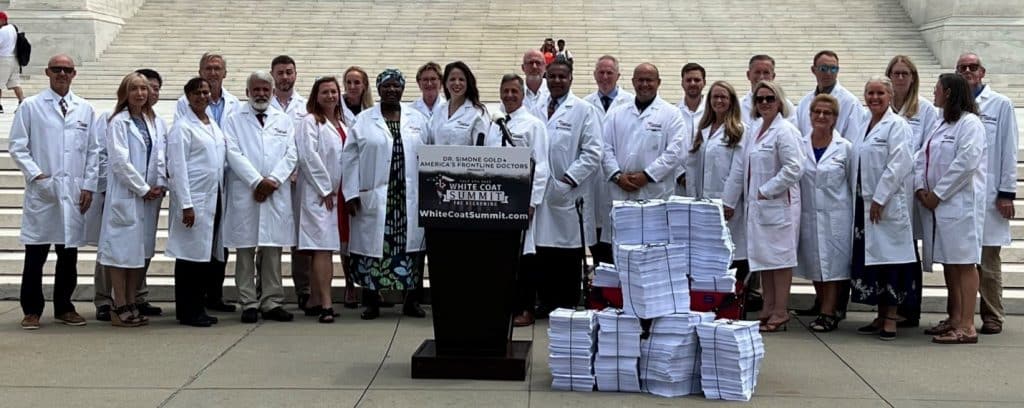

Take, for example, the bizarre and alarming instance of the ‘Birds Aren’t Real’ movement, an initially humorous parody of a conspiracy theory, which claimed that birds are government surveillance drones. While absurd on the surface, its widespread discussion on platforms like TikTok and Instagram reflects how easily Gen Z can be swayed into entertaining and potentially even believing in such far-fetched ideas.

The realm of politics isn’t immune either. Conspiracy theories like QAnon do not just warp political views; they have led to alarming incidents and real-world violent actions, including the storming of the Capitol in Washington. People who once might have been passive observers are now being radicalised into taking extreme and sometimes unlawful actions based on these unfounded theories.

In terms of environmental impact, the conspiracy-driven denial of climate change among Gen Z can have long-lasting repercussions. This isn’t just skepticism; it’s a disturbing dismissal of scientific evidence, leading to apathy and resistance towards environmental conservation efforts, further exacerbating the climate crisis.

This unchecked spread of misinformation comes with stark consequences. Young minds, still forming their worldviews, are bombarded with claims that challenge and often contradict established facts. The shock factor here is not just in the content of these theories but also in the ease with which they spread and the depth of their impact. These aren’t just background noise; they are actively shaping Gen Z’s perceptions and decisions, often in ways that are counterintuitive and potentially harmful. It distorts their understanding of science, history, and current events, leading to a generation that may be increasingly skeptical of facts and more susceptible to fringe beliefs.

This susceptibility is not merely a matter of being misinformed; it’s a gateway to deeper societal issues, including polarisation and the erosion of trust in institutions. The shadowy side of the internet, largely unknown to many, poses a silent but significant threat to the fabric of our society.

In today’s world, where information is a constant barrage, media literacy and critical thinking aren’t just good skills to have; they’re essential survival tools. These skills teach you not just to question the authenticity of what you read or watch, but also to understand the intentions behind the information. It’s about becoming a savvy navigator in the sea of digital content, where you’re as much a detective uncovering truths as you are a consumer of information. By honing these skills, you’re equipping yourself to stand firm in an era where facts and fiction often blur, ensuring you remain grounded in a world that’s constantly trying to sway you.

If you’re concerned about what information you might be consuming, start by tuning into your emotional GPS. Are conspiracy theories making you feel anxious or overly suspicious? Acknowledging these feelings is the first step in building a mental firewall against manipulation. When you encounter a conspiracy believer, it’s like stepping into a hall of mirrors. Will you find your way through with calm reasoning, or will confrontation only lead you deeper into the maze? Remember, every interaction is an opportunity to practice empathy and maybe, just maybe, gently guide someone back to reality.

This digital realm, often unseen but actively shaping the perceptions and decisions of Generation Z, poses a silent yet significant threat to the fabric of our society. From misinformation about public health to the erosion of trust in institutions, the impact of these theories is profound and far-reaching.