It’s 2017, the weather is swelteringly hot, secondary school has just started, and two 13-year-old girls are sat side by side in a rowdy classroom discussing a seemingly very serious matter. My best friend and I are exchanging conspiracy theories. Having just made friends not too long ago, we were stoked when we discovered a common interest in conspiracy theories.

I had been fairly new to conspiracy theories, and any and all conspiracy theories caught my attention. Cherryl, my best friend and partner in crime, on the other hand, had been into the conspiracy theory scene for a while now. When she encountered a YouTube video covering a conspiracy theory involving Taylor Swift, she clicked on it, thinking I would love to hear about it.

Who would want to hear a conspiracy theory about a celebrity they love? Well, me. I didn’t (and admittedly still don’t, despite being a huge Swiftie) keep up with Taylor Swift much apart from her music releases. Hearing conspiracy theories about her was intriguing as much as it was amusing. Cherryl, on the other hand, was and remains a non-Swiftie (although I did drag her to the Eras Tour with me). She had clicked on the video out of pure boredom, and because she knew of my love for conspiracy theories and Taylor Swift.

The 2009 MTV Video Music Awards had been going strong until Taylor Swift was awarded the Best Female Video award. Things took an awkward turn when Kanye West interrupted her acceptance speech and proclaimed that Beyoncé should’ve won, instead.

According to YouTube, this was no random act – things had been perfectly set up for Kanye West to jump up on stage and steal the show from Taylor Swift. After all, he had been given a front seat with no guards stationed in front of the stage, giving him convenient access as he pleased.

Who could have set this up? Certainly not MTV, as former producer Jim Cantiello explained, because staging the incident even as a skit since could have potentially strained relations between the three biggest artists of 2009 (Kaufman, 2019).

Among the crowd of shocked and aghast faces, one person in particular stands out. Dubbed “Queen Bey” by her fans, According to the YouTuber, Beyoncé is one of the leaders of the Illuminati. Think about it: Beyonce and her husband, Jay Z, seem to be living on a whole different plane of success, opulence, and power. Plus Beyoncé occasionally flashes a hand symbol that makes a triangle, which is often associated with the “Eye of Providence”, in turn often linked to the Illuminati.

Historically, this Eye of Providence originated as a Christian symbol (Wilson, 2022). The three points of the triangle symbolise the Holy Trinity (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) with the eye representing the Christian God. The Illuminati were inspired by Freemasonry, which had occasionally incorporated the Eye of Providence as a symbol of God – as seen alongside many other churches at the time. As such, the Eye of Providence became a symbol for the Illuminati.

Beyoncé often employs religious symbols and acts in her creative direction. Her 2017 Grammys outfit incorporated intricate gold pieces and a gold halo crown to frame her as a goddess. This gave conspiracy theorists more fuel to stoke the flames, suggesting Beyoncé was one of the supreme leaders of the Illuminati.

The conspiracy theory YouTube video also talked about this as an “entrance exam” that people looking to be inducted into the Illuminati had to undergo, involving public humiliation. These humiliation rituals are done (not just by the Illuminati… if they actually existed) to emphasise stark differences between social status (Origgi, 2021). Passing the hazing process entails internalising the shame, feeling humiliated, and accepting the loss of social status.

If this was a hazing process by the Illuminati towards Taylor Swift, who was 19 at that point of time, she took the humiliation like a champ. After Kanye West handed the microphone back to Taylor Swift, she stood in silence holding back tears. Of course, the torrent of tears came gushing out backstage, but in the public moment, Taylor Swift had accepted her humiliation and her loss of public status immediately, as demonstrated by her lack of retaliation to Kanye West’s intervention.

Taylor was scheduled to perform in the following portion of the event. Drying her face and plastering a smile onto her face, she performed her song “You Belong With Me” with no hesitations (although with a shakier few last notes). “Also, she changed into this red dress for her live performance. She wore this same red dress for her next appearance on stage,” Cherryl recounts from the video.

Beyoncé would then go on to win Video of the Year Award for “Single Ladies” where she was invited on stage in a beautiful red number. During her acceptance speech (which, thankfully, no one interrupted), she invited Taylor Swift back onto stage to continue her unfinished acceptance speech from before.

Both celebrities are looking gorgeous in their red dresses. But was it a coincidence that both were wearing red after the incident? As the YouTube conspiracy theorist explained, red is especially significant as it holds a hidden meaning of power and influence (Melling, 2019). Taylor Swift had started in a sparkly silver dress but, after her humiliation, she had made the switch to a red dress – of all colours she could’ve chosen from. This could be to symbolise how she was knighted and accepted into the Illuminati by Queen Bey herself, having passed the initiation process.

Conspiracists have long since rumoured that the Illuminati grants people fame, power, influence, and whatever they wish, as long as they are willing to give up something precious to them in exchange for the wish. It is alleged that Kanye West sacrificed a family member in exchange for fame. There are rumours that Katy Perry and Lady Gaga sold their souls to the devil in exchange for unparalleled fame and fortune. Now, similar rumours trail behind Taylor Swift, that she gained her fame through selling her soul… rather than by her own hard work and talent.

It also does not help that Taylor Swift appears to love the number “13”, and makes an effort to incorporate it into her career. It appears in the number of songs in an album, album release dates, and “easter eggs” in her music videos.

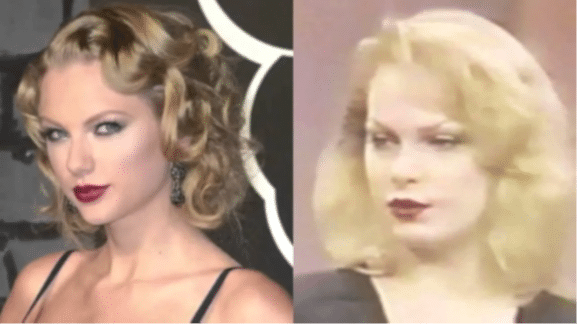

Additionally, conspiracy theorists spread the rumour that Taylor Swift is a clone of former satanic leader Zeena LaVey due to their uncanny resemblance to each other. Zeena LaVey is an American visual artist and musician, and the daughter of the founder of the Church of Satan; she was High Priestess of the church from 1985 to 1990.

When I asked my best friend what it was about this 2009’s VMA theory that she had been intrigued by, her answer was reassuring. It was the “sheer absurdity of the theory” that “brought her much entertainment and made her laugh”.

Initially, back in 2017, Cherryl and I did not believe a single word of this theory, but over time it began to appeal more to us. Taylor Swift’s boom in success in her career after that incident certainly didn’t seem too much like a coincidence – she released hit after hit album following the 2009 VMAs, escalating her career in the music industry, becoming one of the world’s most spoken-about artists. Thus, our 13-year-old selves concluded that the theory must be true, and Taylor Swift had gained her extraordinary fame as a result of Beyoncé accepting her into the Illuminati.

However, now that we’re both older and have developed some critical thinking abilities, we can both confidently state that we do not believe that Taylor Swift is a member of the Illuminati. “From what I’ve seen about Taylor Swift online”, Cherryl told me recently, “it’s kinda obvious that her fame is well-deserved and all as a result of her own hard work.”

Outside of the conspiracy theory, the real story of the VMAs is far more understandable. According to Billboard, both Taylor Swift and Beyoncé were crying behind the scenes after the incident (Kaufman, 2019). Why would Beyoncé be crying if she were one of the supreme leaders of the Illuminati and had clearly set up the whole incident to test Taylor Swift? Moreover, Beyoncé was actually prompted by producers before her own award was presented to hand the show back to Taylor Swift to continue her interrupted acceptance speech.

And perhaps Kanye West being seated in the front row with no bodyguards stationed nearby was more of an oversight by MTV than the setup of an initiation ritual. Kanye West had been drinking that night, as seen by paparazzi pictures of him holding a Hennessy bottle. Alongside his history of egotistically jumping on stage, it’s really not all that surprising that interrupted Taylor Swift’s moment of glory.

And while there’s not much to be read into Taylor Swift’s costume change, given how frequent costume changes are at awards ceremonies, we can be in little doubt that this conspiracy theory is just a conspiracy theory.

Taylor Swift’s sheer tenacity and creative prowess has got her to where she is now – one of the most successful musical artists of all time. These conspiracy theories often target female celebrities in a bid to rob them of the ownership of their own hard work, resilience, and determination to succeed. Taylor Swift’s success can be fully attributed to her top-tier and unique songwriting skills, her brilliant and borderline terrifying attention to detail, the relatability of her songs, and much more – not to a secret and powerful organisation who has bestowed success upon her.

Alongside this ridiculous theory about Taylor Swift being part of the Illuminati, there are also myriad other conspiracy theories that are equally wide of the mark, the latest being that she is a secret Government Agent to help Biden win the 2024 Presidential Election.

These conspiracy theories are often rooted in underlying misogyny – while similar rumours exist about male celebrities selling their soul in exchange for fame, the issue of whether they deserve their fame is not brought up as often as in relation to female celebrities. For example, Lil Uzi Vert, a rapper who has alluded to having sold his soul to the devil and other outlandish claims, is not subjected to the same scrutiny as to whether his talent is authentic.

Now, Taylor Swift is revelling in her well-earned position as one of the best music artists of all time while Kanye West is… somewhere trying to revive his declining career. Despite the incident (and not to mention multiple other horrific interactions between Kanye West and Taylor Swift), it’s safe to say that Taylor Swift has the last laugh.

References

- Cohen, J. (2020, January 23). Revisiting Taylor Swift and Beyoncé’s supportive history. E! Online.

- Grady, C. (2019, August 26). How the Taylor Swift-Kanye West Vmas scandal became a perfect American Morality Tale. Vox.

- Ishler, J. (2016, September 9). There’s a crazy conspiracy theory that Taylor Swift is the clone of a former satanic leader. Medium.

- Kaufman, G. (2019, August 27). 2009 VMAS oral history: What you didn’t see when Kanye West rushed the stage on Taylor Swift. Billboard.

- Kreps, D. (2019, September 11). Kanye West storms the VMAs stage during Taylor Swift’s speech. Rolling Stone.

- Lyttle, Z. (2023, December 13). Celebrate Taylor Swift’s birthday by the numbers: 3 pet cats, 27 vault songs and everything else between 1 and 34. Peoplemag.

- Melling, E. (2019, October 24). Color theory – the hidden meanings of red. Yes I’m a Designer.

- Origgi, G. (2021, February). Ground zero. the triangle of humiliation.

- Rosa, C. (2017, February 13). Beyoncé was a literal goddess for her Grammys performance. Glamour.

- Wilson, M. (2022, February 24). The eye of providence: The symbol with a secret meaning? BBC News.

- Wurzburger, A. (2019, August 26). Everything Taylor Swift and Kanye West have said about the “im’a let you finish” speech. Peoplemag.