With over 40,000 deaths in the UK and over 800,000 worldwide related to COVID-19 at the time of writing, you’d be forgiven for not having dental issues at the forefront of your mind at the moment. Unless that is, you’re one of the many people who have read about the new dental phenomenon known as ‘mask mouth’.

I hadn’t heard about mask mouth until a dentist friend of mine pointed me in the direction of an article on David Icke’s website. Icke’s site links to an original piece in the Daily Mail, and the story also made it into The Sun and Glamour magazine (now removed but available via archive), among others. You might think that these aren’t the most reliable of sources, and you’d probably be right, so it’s worthwhile looking at these claims to see if they stand up to scrutiny.

As the story goes, the wearing of facemasks during the pandemic is causing an ‘explosion’ in the number of patients suffering from both cavities in their teeth and gum disease. People who have had no previous history of dental problems are starting to have issues with their teeth, and according to the dentists interviewed for the articles, it’s affecting up to half of their patients.

But are these claims realistic, or are they simply a confection? Let’s start with the claims that wearing a mask leads to tooth decay.

Decay, or ‘dental caries’ as dentists like to call it, is one of the most common diseases worldwide. To experience decay, you need four things: teeth (obviously), bacteria, a fermentable substrate (for this; read sugar) and time. Remove any of these, and you remove the chance of decay.

Of course, it’s a little bit more complicated than that. The decay process occurs when the bacteria in the mouth break down the sugars you ingest into acids. If these acids demineralise the surface of the tooth faster than your saliva (or artificial alternative) remineralises it, your tooth begins to decay. The bacteria in the mouth live in a complex colony called a biofilm, which is removed for a short period when you brush your teeth.

by K. D. Schroeder, CC-BY-SA 4.0

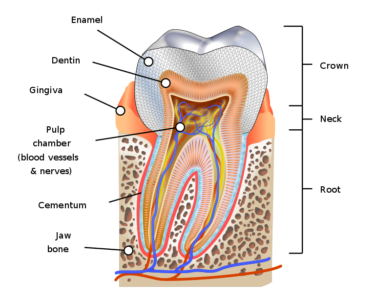

It’s worth a brief interlude here to discuss the anatomy of the tooth Teeth consist of three types of hard tissue: enamel, dentine and cementum. These protect the pulp, which is where the tooth receives its nerve and blood supply. If decay reaches the pulp, you tend to end up with toothache of the agonising kind.

Enamel is the hard-outer layer; the first line of defence for the tooth against the outside world. You probably help strengthen this layer by using a fluoride-containing toothpaste. And if you don’t, you should.

The dentine layer of the tooth lies just below the enamel and consists of microscopic canal-like tubules. These tubules contain projections of the pulp and it’s these pulpal projections that cause the sensitivity you may experience when you have something particularly cold. Sensitive toothpastes work by either blocking the tubules or reducing the responsiveness of the pulp

Cementum covers the root surfaces of the teeth and helps attach to the bone of the jaw via the periodontal ligament. You’re only likely to experience decay of the cementum if you’ve had a significant amount of recession of the gums due to long-standing gum disease or trauma.

Dentine and cementum have lower mineral content than enamel. If the decay reaches these deeper layers, it’s likely to spread more quickly, so what we characteristically see is decay breaching the enamel and blooming at the junction between the enamel and dentine. It’s not unusual for what appears to be an insignificant cavity on the surface to be much more sizeable when you get into it.

With that short dental biology lesson complete, we can return to ‘mask mouth’, and ask: is the wearing of masks likely to be a factor in the decay process? In short, the answer is no. Wearing a face covering doesn’t affect the bacteria in the mouth, and it doesn’t increase the amount of sugar you take in. For the short amount of time that most of us will be wearing masks in our everyday lives, the effect on the oral environment is likely to be negligible.

But what about gum disease? Perhaps unsurprisingly this looks unlikely too.

Gum disease is an inflammatory disease of the tissues that surround the teeth. We generally divide this into two types, gingivitis and periodontitis.

Gingivitis is the gum’s inflammatory response to plaque. Importantly, gingivitis doesn’t cause loss of the bone that supports the teeth – that bone loss is a sign of the less common, but more severe, periodontitis. Again, we know that gum disease can be controlled, for most people, by efficient biofilm disruption. And by that, I mean brushing your teeth well. Make sure to concentrate on the gum line, where the biofilm starts to grow; and use interdental brushes or floss to clean in between your teeth regularly.

For most people, the bone loss associated with periodontitis may take years to become apparent. By the time patients have noticed symptoms, which usually involve loose or drifting teeth, the disease can be at an advanced stage. Wearing a mask for the last few months, even if you were doing it for hours every day, is not going to accelerate that process.

Speaking of which, do you know who is wearing masks for many hours a day, every single day at the moment? Dentists. Sure, we are probably a bit better than most at keeping our teeth clean, but there simply haven’t been any reports of dentists developing ‘mask mouth’. And, come to think of it, other than the one or two dentists cited in the mask mouth articles, I can’t think of a single dentist who has even heard of it.

What is ‘mask mouth’ then? One answer might be that it is a cynical ploy to drum up trade by a handful of dentists who haven’t been able to work during the coronavirus pandemic. And that’s what really leaves a bad taste in the mouth.