Earlier this month, Time magazine published a striking news article highlighted on its cover: the dire wolf is back. The newsmaker was a biotechnological company called Colossal Biosciences, which focuses on de-extinction of species that no longer exist. Across numerous magazine articles, they shared the photos of three nice snow-white pups with wolf-like faces and claimed that they are representatives of Aenocyon dirus – a canid species that roamed across the Americas until the end of the last Ice Age, and went extinct after the intrusion of the first humans.

Dire wolves are familiar to modern people due to the TV series Game of Thrones, which even provided reference for the name of the youngest pup, a little female wolf, Khaleesi. Two other pups were called Romulus and Remus — in honour of the fabulous founders of Rome which were suckled by a she-wolf. But are they really dire wolves? Do they really belong to the same species that inhabited the Americas ten thousand years ago?

First of all, significant biological results are usually published as academic papers. They contain detailed scientific descriptions of the discovery itself and the methods that led to it. This format allows us to understand the results comprehensively and decide how to interpret them. If the review process of a traditional journal seems unacceptably slow for disclosing the urgent results, there is an option of preprint.

bioRxiv, the largest preprint server for biology, aggregates thousands of early-stage papers, which are posted immediately to be discussed in the scientific community, while a final edited version is undergoing a thorough peer-review process. But Colossal Biosciences has not even posted a preprint about their “resurrection” experiment, to say nothing about a formally published article.

All we have is the press release from a company – the least informative form of scientific communication. The article in Time and information on the commercial website (arranged rather more in a commercial style than in a scientific style) is insufficient for critical analysis. This undermines any trust we might have in the company’s claims: broad statements like resurrection of a new species cannot be taken on faith and marketing.

Having no proper scientific publication, we are forced to discuss the few details available in press releases. But even these details throw the claims of “de-extinction” into question. Colossal Biosciences has deciphered the genome of a dire wolf – this is the only part of their work on which they have published a paper as a bioRxiv preprint. The company claims that they have further identified key genes responsible for the characteristic traits of dire wolves, and edited those respective genes in common grey wolves. In total, researchers edited 14 genes corresponding to 20 phenotypic traits, including a white coat, larger size, and characteristic vocalisations, such as howling and whining.

If one edits 14 genes in the genome of a grey wolf, is this sufficient to render it a new species? The exact answer depends on the criteria of species we use.

If we start from a genetic criterion, the answer will be evident. Gene editing introduces far fewer changes into a genome than traditional breeding. Even 14 changes represent a negligible proportion of the whole canid genome, which contains around 19,000 genes. So, from the genetic point of view, three fluffy white pups of Colossal Biosciences differ from a random grey wolf living in a forest less than a spaniel differs from a husky. But both a spaniel and a husky are considered to belong to the same species. A subspecies of grey wolf, by the way.

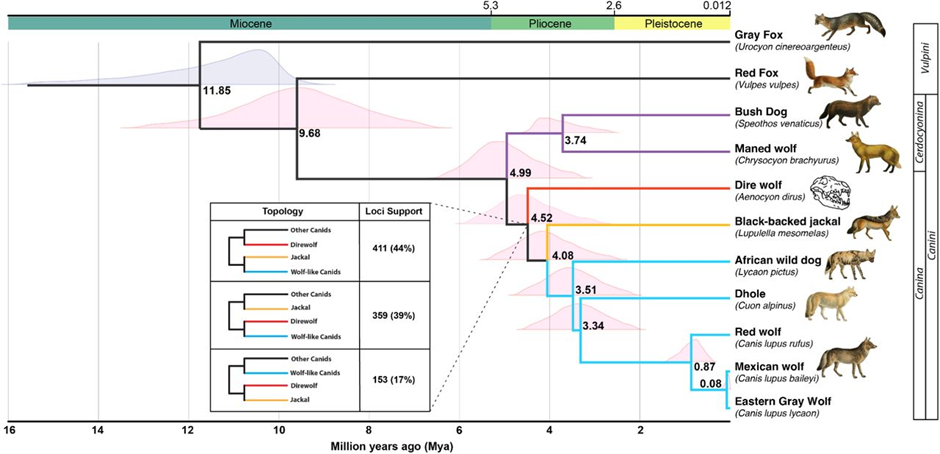

Let’s also remember that dire wolves and modern grey wolves are separated by a huge evolutionary distance. Their last common ancestor lived more than four million years ago, and dire wolves are more distant from grey wolves than coyotes and jackals. In contrast, if we read the genome of Romulus, Remus, or Khaleesi, they will almost merge with grey wolves on the phylogenetic tree. They are so far apart on the evolutionary scale that it would be absurd to attribute these three fluffy canids to the Aenocyon dirus species.

If the most genes in Colossal’s pups are still of lupine origin, their physiology and biochemistry should be almost the same as of regular grey wolves. We still have the last criterion of species to consider: a reproductive criterion. Individuals are normally considered as the parts of a same species if they can crossbreed and give fertile offspring. We cannot check this criterion directly; the last dire wolves, which could be controls, are extinct.

Even if we could, this experiment would be far from insightful. The canid family is rich in interspecies hybrids: wolves can give viable and fertile hybrids when matched with jackals and coyotes, but they are considered separate species. Even the successful hybridisation with dire wolves would not mean these gene-edited pups should be recognised as dire wolves.

In the 2000s, when I was a schoolboy, I engrossed myself in reading magazines with futurological predictions. They promised that by 2035 we would have gene-edited pets with external features of their wild counterparts. For example, domestic cats that look like small lions. The case of Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi is highly reminiscent of such “customisation” of animals. A hypothetical lion-like cat will not become a real lion, it’s just a slightly tweaked cat (and that’s for the best – its owner has no need to worry that they would be eaten someday instead of Whiskas). Likewise, the pups of Colossal are not dire wolves – they are customised grey wolves.

Surprisingly, this could be the greatest take-home message from the “dire wolf” story and a real step of progress. The work of Colossal Biosciences is valuable as a case of gene editing of a mammal, and it could possibly pave the way to industrialising this technique and starting to use it en masse. What if we really are on the cusp of the era of gene-edited pets? It could offer the shocking prospect of having a lion-like maned cat… or a dog that looks like a dire wolf. These techniques could change an animal’s appearance, without having to undergo a long breeding process and risk undesirable effects such as hereditary diseases.

This technique could offer some more tempting prospects – for example, the industry of gene-edited animals to grow organs for transplants. Colossal Biosciences really has made a great scientific advance – not in de-extinction, but in animal customisation.

Indeed, the company is forced to take a pragmatic approach to the problem of de-extinction. The full instruction to make a new (or a well-forgotten, old) species lies in its DNA, and the only way to re-create a species is to express its full genome in a new organism. However, it is technically difficult to synthesise the whole mammal genome to render it fit for expression in a new cell. And, even in the case of success, the created embryo of a new species could be incompatible with any of the extant female animals – there will be no mother for it.

In these conditions, all we could do is to render an extant species to make it resemble the extinct one. Colossal Biosciences works hard in this direction: they have already created woolly mice on their way to a more ambitious goal – create a woolly elephant that could serve as a “resurrected mammoth”.

The advocates of such an approach say that we need to fill the ecological niches of the extinct species – and such “customisation” is a good option. Here we, all of humanity, act as collective customers – thus the biotechnological industry is focused on customisation of wolves and elephants, not domestic pets (they can wait).

These considerations have one significant drawback: ecological niches have significantly changed for thousands of years, and the “resurrected” animals share the majority of genes with their common extant counterparts. This way, their ecological behaviour might differ from the expected one. This is one more criterion of species – an ecological criterion – and only long, natural experiments could show whether it is met or not. Only at that moment could we hypothesise a partial resurrection of the extinct species – if the experiment will be successful.

Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi are not an answer, but a living question to science. And the answers will eventually be published as academic articles – not press pieces in Time magazine.

Cover image: Ed Bierman/Flickr/CC BY 2.0