Joe Rogan is an interesting character when it comes to skepticism and conspiracism. While we might assume that everyone knows who Joe Rogan is, it’s easy to overlook him, especially in the UK, when you’re not his target audience.

Rogan is an American comedian and Ultimate Fighting Championship commentator, but these days he’s most famous for his podcast, the Joe Rogan Experience. It’s an incredibly prolific show – since launching in 2009, he has published over 2,300 episodes (our own podcast, Skeptics with a K, was launched the same year, and is still in the early 400s in terms of episode number).

The most staggering thing about the Joe Rogan Experience is its phenomenal reach. It is the number one podcast, according to Spotify, in the UK, US, Australia, Canada and New Zealand. It has amassed 19.7 million subscribers and over six billion views on YouTube alone. With that reach comes impact; researchers have identified that an appearance on Rogan can secure his guests a significant lift in book sales. Within a week of appearing on the show, pseudohistorian Graham Hancock saw a 519% increase in book sales. Claims made by Rogan’s guests regularly dominate the media discourse in the days after their appearance airs.

What does Joe Rogan do with this significant power in the media? Mostly, he interviews and platforms people with wild conspiracy beliefs, who often make quite dangerous claims, almost entirely without challenge (although there are podcast projects taking up that challenge).

Amid all of this, it’s easy to unconsciously dismiss the Joe Rogan Experience as just a place where the ‘cranks’ go to talk about their ‘crank views’. But with a listenership as sizeable and significant, there’s plenty within Rogan’s audience who wouldn’t describe themselves as conspiracy theorists, despite the media they’re consuming. And that means that some of the more fringe ideas that are circulated on Rogan’s show are suddenly accessible a huge audience, where they might start to take root.

Take, for example, fenbenzadole. The first mention of fenbenzadole on Rogan appears to happen in October 2023, in an interview with Graham Hancock wherein they discuss the initial postponement of Hancock’s debate with archaeologist Flint Dibble, due to Dibble’s cancer diagnosis. During the discussion, Joe spontaneously mentions fenbendazole – a medication he had presumably come across on Instagram or Twitter, since he goes to his saved posts during the episode in order to find its name. According to Rogan, “It’s some sort of a very low-cost drug that’s being repurposed. I think it’s some sort of an anti-parasitic drug that’s being repurposed and is having supposedly remarkable results.”

Having found the saved post, appearing at the time on a website called “vigilantnews.com”, Rogan proceeds to try to read the highly technical language outlining what is said to be so remarkable about fenbendazole:

[It] has at least 12 proven anti-cancer mechanisms in vitro and in vivo. It disrupts microtubulate polymerization, a major mechanism, induces cell cycle, whatever that means, arrest, blocks glucose transport, and impairs glucose utilization by cancer cells, increases P53 tumor suppressor levels, inhibits cancer cell viability, inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion, induces apoptosis, induces autography, induces… They’re trying to get me with all these words. Preoptosis and necrosis, induces differentiation and senescence, inhibits tuner angiogenesis, reduces colony formation and inhibits stemness in cancer cells, inhibits drug resistance and sensitizes cells to conventional chemo as well as radiation therapy. A very similar drug in the same family has already been approved by the FDA. And that is mebendazole. And it is in several clinical trials right now for brain cancers and colon cancers. So why are [there] no fenbendazole clinical trials for cancer?

This is clearly in the “huge if true” category, so what actually is fenbendazole?

Fenbendazole

Fenbendazole is a wide spectrum anti-parasitic medication that’s used for sheep, cattle, horses, fish, dogs, cats, rabbits and seals. It treats a range of gut parasites like hookworms, roundworms and tapeworms. It works by binding to a protein called tubulin, which makes up microtubules – exactly as Joe Rogan read. Microtubules are a crucial part of the cell’s structural system, and when microtubules can’t form properly due to this binding, the cells eventually die.

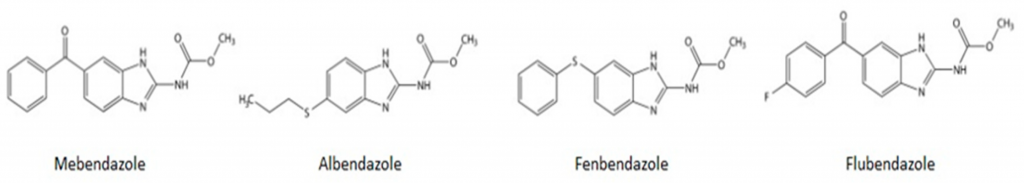

Mebendazole, the other drug Rogan mentions, is essentially the human version of fenbenzadole. It’s given to people to treat threadworms and other gut based parasitic infections. And, surprisingly, much of what Rogan is reading out is actually scientifically reasonable. Drugs that bind to tubulin will have an impact on apoptosis, cell migration, autophagy, differentiation, senescence and p53, which is very frequently mutated in cancer. And drugs that bind to microtubules are also given as anti-cancer medications. For example, docetaxel is a chemotherapy that targets microtubules, used against a range of cancers including breast, lung, prostate, stomach, head and neck, and ovarian cancer.

Rogan is right about something else, too: there are pre-clinical trials, and some very early clinical trials, investigating mebenzadole for use in cancer treatment, and they show some promise. There are also early pre-clinical trials investigating fenbenzadole for cancer therapeutics, too.

But here’s the issue: these two treatments not being rolled out for patient use yet has absolutely nothing to do with big pharma thinking they’re not marketable. Getting a medication from conception through to patient use is a phenomenally expensive process with a high failure rate. Pharmaceutical companies love an opportunity to use a drug that’s already reliably used in humans, already has some safety data available, and already actually does the thing you want it to do – in this case, bind to tubulin and disrupt the microtubule formation. We see this in business all the time; taking something that already exists and bringing it to another market for a higher price to make a good profit.

It doesn’t take something being available cheaper elsewhere to prohibit sales for the same thing at a higher price point; people will spend more for the same thing for a whole range of reasons, including brand loyalty, a trusted source, convenience or accessibility. If fenbendazole was actually approved as an anti-cancer medication, healthcare organisations would be lining up to buy it from a pharmaceutical company, rather than a veterinary practice, and patients are much more likely to want to take it if it’s prescribed by their oncologist instead of having to buy it online from a random source. That is likely even true in places like America, where insurance companies (or a lack of insurance) come into the equation, but where there are plenty of ways to justify why it’s important to buy a medication from a pharmaceutical company, even if the drug is identical to one sold elsewhere.

But even taking that out of the equation, mebendazole and fenbendazole aren’t very good drugs for this purpose at the moment, because they don’t pass across the gastrointestinal barrier well. This is good when they’re being taken as antiparasitic drugs for gut parasites, since there’s very low toxicity for the patient as a result but decent toxicity for the parasites. It makes it a safe and reliable treatment. But, if we want to treat cancer, we need the medication to get further around the body, depending on where the tumour is.

If mebendazole or fenbendazole are to be effective as anti-cancer medications, we need to figure out a way around that, which means changing the molecular structure of the medication somehow. That might mean adding something to the drug to help it get into the system better, or changing how it’s administered – perhaps instead of an oral tablet, it might need to be injected. These are things that pharmaceutical companies can test and patent, so that their version of the drug is the effective one – and the saleable one.

When Rogan asks on air, “Why aren’t there clinical trials for fenbendazole?” his guest, Graham Hancock, provides a confident answer (about the medication he’s only just heard about): “Big Pharma don’t see a margin in it.”

To which Rogan replies: “I mean, if that, who knows? But if that is the case, I mean, what an enemy of the people. They’re preventing information and preventing people from using things.”

Rogan’s said ‘if’ – so he might argue that he’s not saying it’s definitely the reason… but he is clearly implying it, and leaving it to his (well-trained) audience to make that connection. But he’s flipped the narrative here: instead of saying “researchers have found that mebendazole might be useful, so they’re starting to do pre-clinical trials and then clinical trials, and then they’re following the same route with fenbendazole, but they just started a bit later on that one so they haven’t got as far as clinical trials yet” he’s saying, “Why are They withholding progress on fenbendazole?”

The truth is, we don’t know yet whether these two medications will prove to be reliable for cancer use. We do not have enough data to say either way. There are countless medications that seem “promising” for cancer, but turn out to be useless once we give it to human patients. In fact, in the case of mebendazole, as promising as it may be for treating and even preventing some cancers, there’s data to suggest it might also accelerate the progression of some other cancers. We need to do more research to make sure it is effective as an anti-cancer medication, can get to where it needs to get to treat those cancers, and is safe for use as an anti-cancer medication. There’s a lot of research left to do, and until then it’s just not safe to use this medication to treat cancer.

It might seem like there’s no harm here – after all, these two medications are minimally toxic in humans. But low toxicity is not zero toxicity. There are also risks associated with taking the wrong medication for your cancer diagnosis – we need to make sure that we’re being safe and taking something that works, and, if we eschew what the oncologist says and take something else, we might be avoiding a treatment that truly works in favour of one that doesn’t.

Mebendazole is in clinical trials for glioma – a brain cancer that we find exceptionally hard to treat. If you decide to take it experimentally for something like breast cancer, which we’re really very good at treating, you’re potentially missing an opportunity to take a treatment that works in favour of something we just don’t have evidence for.

In addition, there have been cases where patients have taken fenbendazole and been considerably unwell, including one patient in Japan with non-small cell lung cancer who took fenbendazole based on social media advice and ended up with drug-induced liver damage. Thankfully, after the patient ceased their month-long course of fenbendazole, their severe liver damage resolved – but after a month of the treatment, there was no evidence of tumour shrinkage in her case.

This case was widely reported in 2021 – long before Rogan found a post on a dubious-looking website that persuaded him to start talking up the benefits of fenbendazole.

In fact, fenbendazole has circulated as an alternative therapy for cancer treatment on social media for a while. A study published out of South Korea titled “How cancer patients get fake cancer information: From TV to YouTube, a qualitative study focusing on fenbendazole scandle [sic]” explains:

The fenbendazole scandal was an incident wherein false information that fenbendazole, an anthelmintic used to treat various parasites in dogs, cured terminal lung cancer spread among patients. It started with the claim of American cancer patient, Joe Tippens, but rather became sensational in South Korea.

The truth is, Joe Tippens was also part of a clinical trial for a new anti-cancer medication, but under the care of a veterinarian he chose to attribute his survival to taking what is now referred to as the ‘Joe Tippens protocol’ of fenbendazole plus vitamin E supplements, CBD oil, and bioavailable curcumin. The news really took off in South Korea, when a local comedian shared his intention to take fenbendazole for his cancer diagnosis. The comedian later shared that he would not take or recommend fenbendazole and ultimately died from his cancer in 2021.

In a study researching the impact of the social media misinformation around fenbendazole in South Korea, a survey of 86 people living with cancer showed that “about half of the cancer patients had taken non-prescription anthelmintics during their chemotherapy, and 96.5% of them did not inform the clinicians.”

Meanwhile, Rogan – at least in this interview with Hancock, where he first discusses fenbendazole – never actively recommends that people should take it. He says of Flint Dibble: “I hope he’s interested in even just examining it”. He comes across as relatively balanced on the whole thing, even saying

The problem is when these people that are creating these incredible drugs, these scientists and doctors and these people that are having these amazing medical advancements, they’re connected to something that just wants to make money. The people that are selling the drugs and the people that are running the companies are completely different than the scientists that are legitimately developing these things, and many of them turn out to be very effective for all sorts of ailments and diseases.

Joe Rogan isn’t therefore anti-science – he’ll tell you the science. He’s not even anti-medicine. He just wants to give people access to the best science and the best medicine. And that would be great if mebendazole or fenbendazole were proven to be useful treatments for cancer… but we’re just not there yet, and it might be that we never will be.

In a world where people living with cancer are bombarded with advice and recommendations of ways to treat their cancer, it is doubtlessly tempting to listen when your favourite podcast host talks up the scientific properties of a new or repurposed drug.

But you should never take medical advice from a podcast. Especially not the Joe Rogan Experience.