After forty-five years educating the public about the danger of cults, the Cult Information Centre’s, Ian Haworth, 76, stopped taking phone calls in August this year, but before he disconnected the phone, he agreed to condense four-and-a-half decades of experience into two long-distance telephone conversations.

Ian answers the phone on the third ring, but — despite trading emails for a few weeks leading up to our conversation — it takes him a moment to remember who I am.

“I wasn’t sure which Paul it was.” I ask him if he regularly speaks to a lot of Pauls. “Well, anything’s possible in this field,” he says.

He opens our conversation with a caveat: “You can hit me with anything you want to. It could be personal or otherwise because I don’t have to answer and I’ll be very straightforward with you.”

Despite the disclaimer, Haworth is happy to talk and punctuates his observations and recollections with jokes, anecdotes, and original metaphors that require a mental double-take to keep up.

“Nobody in the right mind would try and do this sort of work for 45 years,” he says as he gives a candid window into the fascinating, often unbelievable, often tragic world of cults.

Not an Expert

An Internet search for information on people working in what is sometimes called the anti-cult field yields the term “cult expert,” which refers to a person (often a former cult member) who raises public awareness about the issue and provides specialised exit-counselling for people leaving cults.

Haworth, however, doesn’t feel comfortable with the title, “I’m a cult specialist. Whether or not somebody wants to see me as an expert is up to them.”

He simplifies his role even further, “I have wanted to be, over the years, available to talk things through with people that want to talk about something to do with cults – whoever they are. And I’ve tried to do that.”

While he might not consider himself an expert, Haworth’s work has seen him in the lecture theatres of universities and schools across North America and the UK, appear in TV and radio interviews, and inside courtrooms to provide expert witness testimony, or—as I learn a little later—on the receiving end of libel suits levelled against him by the groups he’s trying to protect the public from.

His book Cults: A Practical Guide is currently in its fourth edition, and he’s helped found non-profit organisations and charities across North America, the UK, and Europe to help educate the public and support former cult members and families who’ve lost loved ones to cults.

Since 1987, Haworth has been the general secretary of the London-based Cult Information Centre (CIC), one of the few UK-based non-profit organisations set up to help educate and support the public.

In the last few years, Haworth has stopped giving so many talks. “I had to just slow down a bit because I was suffering from O.L.D,” he pauses and then adds, “Sorry, that’s my attempt at humour again.”

Regardless of how he sees his role in the last forty-five years, Haworth has been one of the few on the frontline fighting to protect the public from cults.

From Bolton to Canada

Born in Bolton in 1947 to a family of “farmers on both sides,” Haworth moved to Leyland, Lancashire when he was young, where he grew up on his family’s poultry farm. Back then, according to Haworth, a cult meant nothing more to him than the name for a young horse.

Unsure about his future career options, the young Haworth first dabbled in engineering before settling on business. After a three-month university trip to the US in 1969 and a stint washing dishes in a resort hotel in Connecticut, which Haworth describes as “the best holiday of my life,” he moved to the US. Then, in 1972, a twenty-five-year-old Haworth, concerned about America’s ongoing war in Vietnam and the possibility of being drafted, headed to Toronto, Canada, where he worked for electronics and telecoms companies in various roles, and was a buyer of the first sub-$100 calculators on the market.

Reflecting on his professional ambitions at the time, Haworth says he had absolutely no idea what he wanted to do with his life – but that would all change in the space of a few days when he signed up for a course that promised to help him stop smoking.

“The only time I was convinced that I knew what I had to do,” he says, “Was when I escaped from the cult.”

Encountering the Group

Toronto, 1978, and Haworth – a heavy smoker of seven years – is seeking professional help to quit, and is considering his options. He sees an advertisement for a $220, five-week course boasting a 70% success rate. Researching things a bit more, he encounters another company offering a similar thing; however, this one comes with a money-back guarantee.

“What could be wrong with that?” he recalls thinking, “Well, everything, as it turns out.”

A motel near the Toronto Pearson International Airport provided the venue for the course. Haworth attended on a Thursday evening along with forty other participants – some of whom hoped to see changes in their professional lives or practices; some wanted a more personal transformation. No matter what they were individually seeking, they were all there to improve some aspect of their personality or life, and whatever that was, this course, and the group behind it, promised to deliver.

The opening evening’s session on that Thursday night went on well into the early hours of the following morning. Exhausted and operating on very little sleep, Haworth went to work the next day. Instead of returning home to rest once his workday had finished, he was expected to attend the course again for another evening session.

From the beginning, the group established clear rules to prevent the participants from interacting too much with each other, or questioning what was happening. According to Haworth, everything was “…there to inhibit us from questioning and checking things out.”

The group’s activities were tightly controlled, and designed to force changes in the participants’ behaviour and thinking. Haworth remembers the days well:

We were hypnotised, 16 times in the four-day course without knowing it once. We didn’t eat the normal sorts of food that we would normally eat. Nor did we eat the food as often as we would normally eat it, or at the same time. And the chairs in the room were set up in such a way to work against us.

The intense, long days and nights filled with relentless group activities and controlled toilet breaks, combined with sleep deprivation and hypnosis had a powerful, heady effect on Haworth, “One of the results of being hypnotised, even a few times, never mind, 16, is that you’ll feel good. You’re hungry, you’re exhausted, but you feel good.”

This continued over a few days – that’s all it took. The group’s techniques were so effective that by Saturday afternoon, Haworth hadn’t been for his usual cigarette during the allotted break.

“I was theirs hook, line, and sinker by Saturday midday,” Haworth remembers, “Two evenings, one morning, and I was gone.”

However, he doesn’t attribute this break in his old habit to the course’s efficacy in delivering on its promise, but rather the creation of a new identity — one that belongs to the group, “I quit being me because they turned me into someone else who didn’t smoke,” Haworth tells me.

In their 1994 paper, Pseudo-Identity and the Treatment of Personality Change in Victims of Captivity and Cults, psychiatrists Louis J. West and Paul R. Martin explored how cults use destabilising techniques to disrupt people’s senses of self and cause dramatic changes in their personality and behaviour:

Cases of pseudo-identity observed among cult victims are often very clear-cut, classic examples of transformation through deliberately contrived situational forces of a normal individual’s personality into that of a ‘different person’.

The sudden shifts in Haworth’s behaviour began to concern the people who knew him best; neither his girlfriend nor his roommate could understand what had happened during the space of a weekend that could turn somebody they knew so well into a person they hardly recognised.

He also handed in his notice at work. His boss, noticing the changes in his personality and sensing that something wasn’t quite right, didn’t immediately process the request, “She knew something was wrong, she couldn’t explain it, but she knew I was in trouble,” he says.

The group’s meetings and activities quickly took over all of Haworth’s free time, whether it was fundraising, recruiting people on the streets, or attending courses and meetings, “I was just doing whatever they told me to do,” Haworth explains.

Monday evenings, he’d be attending top-up meetings; Wednesdays, he’d be handling new recruits and getting them to sign up for courses. The group, in a short space of time, had learned that Haworth was a former competitive swimmer, so they arranged for him to teach disabled children to swim at the local hospital on Tuesdays to help boost the group’s image and profile within the community.

He even tried recruiting the people closest to him. One of these people was Haworth’s neighbour. “A very dear neighbour who, like everyone else, I tried to recruit,” he admits.

This neighbour called him one day to tell him the group he’d been non-stop talking about for the past week was in today’s newspaper and invited him to the lobby of their building to receive a copy. Eager to see what good things the press were saying, he immediately returned to his own apartment and opened the newspaper, expecting the article to be full of effusive praise for the group—but what he found was anything but.

Dejection and disbelief replaced excitement – Haworth “fell apart at the seams” as he read horror stories of one former member in a psychiatric unit, and other recent ones in psychiatric care.

The message in the article was unambiguous: This was a cult, and people needed to stay well away.

A shocked Haworth took the article to the group’s leadership, where his questions were met with a tirade about the ethnicity of the journalist. “Why don’t you go away,” they told him, “And come back when you’re feeling better?”

Haworth did leave, but instead of ignoring the article as propaganda or bad press, he decided to call the journalist behind the piece. A forty-five-minute telephone conversation later, the journalist invited Haworth to his office to see the information he had about the group that, but — for legal reasons — couldn’t print.

Haworth wasted no time and immediately jumped on a train, arriving at the newspaper office. The journalist left Haworth alone in the back office with all of his research. A shocked Haworth emerged an hour later, “This is far worse than what you said in the article!” he said to the journalist, who nodded, “Yes, my boy. That’s lawyers for you.”

Persistent influence

Despite the course only lasting a few days, and Haworth only being in the group for two-and-a-half weeks, the techniques used against him had lingering effects.

It was six months before he began to notice certain aspects of his original personality returning, “As time goes by, the cult personality is eroded away, till it no longer exists,” he says.

His desire to smoke returned; however, this was a welcome sign that things were beginning to change, “And when it got to the point after six months where I wanted to smoke again. I was actually happy, because I knew that was normal.”

It was a few months before other aspects of his suppressed, authentic personality began to re-emerge. Again, he—and this time the people closest to him—took this as a positive sign that he was returning to his former self; although, Haworth’s not so sure his friends were happy to see all of his previous traits reinstated:

“After eleven months, my typical painful sense of humour came back as well, and that’s when I knew I was really the old me again. I was back to telling jokes that would make people say, ‘Oh no, Ian” No. Why?’ Come up with a new material please!’” Haworth laughs.

Haworth continued to attend the group’s meetings to warn others, a very dangerous move, he admits, as he could have easily been sucked back in. During this time, he convinced six other members to leave, but the seventh alerted the leadership to Haworth’s activities, and the jig was up—after that, he never attended another meeting or saw any of the group’s leadership again.

After leaving the group, Haworth returned to his former place of work to ask if he could rescind his request and have his old job back. His boss removed the letter of resignation from the drawer in her desk and tore it up in front of him.

Haworth resumed smoking but managed to quit a few years later, this time on his own terms—without the help of anyone or any course.

The World Gets Introduced to Brainwashing.

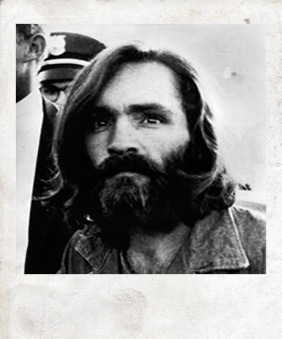

Berkeley, California, 1974. Charles Manson, the notorious drifter-criminal, and mastermind behind the 1969 Tate-LaBianca murders that terrified Hollywood and brought California’s counterculture movement to a bloody close, is three years into a life sentence (commuted in 1972 from the original death penalty sentence).

The highly-televised public trials that once captivated audiences in the US and internationally, and dominated all the nightly news channels, have been replaced by a more pressing national issue—the latest developments about Nixon and the Watergate scandal.

However, Manson is still an unresolved issue in the minds of the American people, psychologists, and the media. Nobody understands or has a definitive answer for how a thirty-six-year-old, 5”2 man, with a slightly above average IQ of 109 could have so much power over a group of middle-class, educated, idealistic young people—known to him as the Family—to have them murder on his command.

Three years after Manson’s sentencing, and 370 miles north of Los Angeles, in the city of Berkeley, the same issues of control, complicity, and coercion, would again be part of the national debate.

On February 4, 1974, the far-left militant group the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) kidnapped newspaper heiress Patty Hearst, then 19, and subjected her to threats and acts of psychological torture (including being locked in a cupboard for weeks) that would, according to some psychologists at the time, constitute to “brainwashing”.

Hearst would go on to be an active participant in the SLA’s bank robberies, and images from CCTV footage from one raid show her shouldering a M1 carbine semi-automatic rifle and yelling at customers, “Up, up, up against the wall, motherfuckers!”

Hearst wasn’t present in the SLA’s hideout when a gun battle with police left six members of the group dead, along with its leader, but she was apprehended shortly afterwards after two failed attempts to kill law enforcement with homemade explosives.

In her testimony, Hearst claims she was coerced and manipulated into participating in the SLA’s activities, and the few psychologists at the time who understood the effects of mind control and thought reform (often known as “brainwashing”) validated her claims.

But doctors on the prosecution’s side described Hearst as “a rebel in search of a cause” and very much in control of her actions, and with no brainwashing defence to help her in the courtrooms, Hearst received a hefty thirty-five-year sentence.

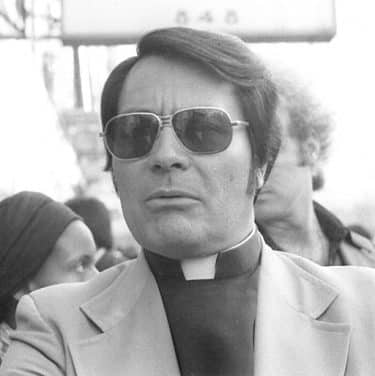

However, an incident five years later would bring the dangers of cults and mind control to international attention. On November 19th, 1979, television media aerial helicopters circle over a 3,800-acre agricultural settlement in Guyana. Strewn around the central structure, the bodies of 918 women, children and men lie face down in the verdant grass. Motionless multi-generational families have their arms draped over one another in one final act of domestic affection; some even have pillows beneath their heads.

(Source: Nancy Wong, via Wikimedia Commons)

On the orders of their leader, the reverend Jim Jones, members of the People’s Temple queued up to consume a cyanide-laced drink in what Jones described as an “act of revolutionary suicide” against the tyranny of the US government.

Parents waited in line, holding their children in their arms as they queued patiently to receive their fatal doses—mothers and fathers squirted syringes into their children’s mouths before ingesting their own.

The event would be the largest death of US citizens before 9/11, and would be known then on as the Jonestown Massacre.

In the wake of Jonestown, American actor John Wayne was one of many vocal supporters of the incarcerated Hearst, and instrumental in the shift in public option about her complicity in the SLA’s crimes:

It seems quite odd to me that the American people have immediately accepted the fact that one man can brainwash 900 human beings into mass suicide, but will not accept the fact that a ruthless group, the Symbionese Liberation Army, could brainwash a little girl by torture, degradation and confinement.

With the tragedy at Jonestown, Hearst’s sentence was commuted to 22 months by then-President Jimmy Carter. She would later receive a full pardon by US President Bill Clinton on January 20, 2001—his last day in office.

And with Jonestown, cults became an international phenomenon and concern.

Haworth remembers the sequence of events very well:

The course started in September, I escaped in October and what happened in November of 1978? Well, Jonestown occurred, of course, in Guyana. The massacre in Jonestown.

One evening, the radio hosts of Canadian radio station CHFI-FM were discussing the tragedy, and—like the rest of the world— were trying to unpack and understand how a single man could get 918 people to not only commit suicide at his behest but kill their children on his command as well.

The hosts discussed whether they should be concerned about such a tragedy happening in Canada and open the phone lines to their audiences for comment.

The phone rings, and the caller is connected. “Yes,” says Haworth, now live on air.

And for the next few moments, the hosts and anybody tuned in on the drive home that evening, listened to Haworth tell his story about the dangers of mind control and cults.

Haworth’s knowledge of a burgeoning topic of interest led to him being invited for a longer interview, which then caught the attention of other media outlets, “I was doing media interviews from that point on,” he recalls.

Council on Mind Abuse (COMA)

Haworth’s first organisation was (the now defunct) Council on Mind Abuse (COMA), which he set up the year after his exit from his group and was the first of its kind in Canada.

COMA would provide the template for Haworth’s UK-based organisation, the CIC, eight years later. His goal in 1979 was to “Warn the public in general. It was to help families. It was to help ex-cult members. It was to help the police. It was to help researchers. It was to help anybody and everybody that was interested in looking at cults.”

He sold all his insurance policies, pooled his finances, and began to give talks and interviews around Canada to educate the public about his personal experiences and the danger of cults. The talks saw him standing in front of high school and first-year university students, members of the Jewish women’s league, and the congregations of local churches.

“I was doing 200 lectures a year,” Haworth says, “It was not unusual, unfortunately, for me to be doing two talks in a day and occasionally three: one in the morning, one in the afternoon, one in the evening.”

In the beginning, he paid for his own petrol and overheads, but as the work and the demand picked up, he realised that if he wanted to continue, he would need to start charging a fee. The dollar price tag attached to the ticket only piqued people’s interest further, and each night, more people would come to see Haworth speak about the dangers of cults, “So then it started to balance out financially,” he says, “I could just about stay afloat.”

From its very inception, COMA and its members had the attention of lobbyist groups connected to and funded by the groups Haworth was trying to warn the public about. The purpose of these lobbyist groups, says Haworth, is “to criticise the critics.”

A few weeks after COMA’s launch, Haworth learned about a meeting at a Canadian hotel about him and his organisation’s activities. He knew nothing about it, and getting the information last minute, he took a car to the location. A panel of academics from a group calling itself the Canadians for the Protection of Religious Liberties (CPRL) had called a press conference in the back function room of the hotel and were preparing to address an audience of journalists.

Haworth arrived five minutes late, and as he entered the room, all cameras, microphones, and lights turned on him.

He introduced himself to the audience as the subject of the meeting; however, out of respect to the CPRL, who had hired the room, he agreed to wait in the corridor and respond to any allegations when the CPRL had finished their address.

Exiting the room, he closed the door just enough so he could hear what was happening inside.

With the proceedings underway, a religious affairs editor for a national newspaper stood up and asked the panel—in a very thick Irish accent, Haworth recalls—if they [the CPRL] were possibly affiliated or connected with any groups that might be considered cults.

The panel looked at each other. “There are none of us here associated with any group that’s been formed in the last 100 years,” replied one CPRL representative.

The editor checked his notebook. “Ah. That’s very interesting,” he said and then asked why a well-known cult (infamous still to this day for ruthlessly going after their critics) was down on the hotel’s records as having paid the CPRL’s bill for the press conference.

Throughout the 1980s, COMA operated out of a secret location and would receive between 100-150 calls a week from members of the public who wanted information. Haworth left the organisation in 1987, but trouble with funding and protracted libel suits with two well-known groups forced COMA to declare bankruptcy and officially close on March 1st, 1992.

A Wing Mirror on Each Shoulder

Haworth is no stranger to the lengths cults will go to discredit or silence anyone bringing negative attention to their activities and practices. The CIC’s website does not list an office address for security reasons, and a company specialising in secure post boxes manages its private PO Box address.

“It isn’t a field people queue up to get into because, if you do, you’re not going to make much of any money and you’re going to get smeared,” he tells me, “And, if you did work all the hours they wanted you to work, then you wouldn’t last very long.”

During our conversations, Haworth uses the word “cult” and the “cult phenomenon” to describe the field at large, but avoids it entirely when describing any individual or collective of individuals.

When we discuss the 418 who starved to death in Kenya when Good News International Ministries pastor, Paul Nthenge Mackenzie, told his followers to begin a deadly fast in preparation to “meet Jesus,” or Smallville’s Allison Mack’s recent release from prison after she was named a co-conspirator in NXIVM founder Keith Ranieri’s sex trafficking and forced labour charges, Haworth avoids the term cult entirely, preferring instead to refer them as “groups” or “groups of concern.”

A defensive tactic, which is “common sense for people in our field,” according to Haworth, who describes how some of his hyper-vigilant colleagues—concerned about the lengths some cults will go to silence or cause problems for their critics—conduct their work with “a wing mirror on each shoulder.”

To illustrate his point, he begins a story about how a friend, an outspoken critic of one group, had the Canadian police call to inform her that they had disturbing photographs in their possession.

These photos showed four men parading around her hometown carrying a coffin. Her name was written in big letters on the wooden lid.

Members of a group under scrutiny or receiving negative press may use intimidation tactics to get a person from speaking out against them, but if the group in question has resources and money on its side, then a libel case can be costly even if you manage to win, “If their lawyer is better than yours, and if they’ve got more money than you, tough. And in addition, you can tell the truth and win, and lose a fortune,” Haworth points out.

When asked if the threats and harassment ever had him reconsidering his position in the field, he’s quick to respond, “I wouldn’t see the point in that,” he says, “It’s not something I want, or I look forward to, but it’s something I anticipated when I started off in the field. It’s just life in the big city when you’re dealing with cults.”

He recounts one incident with his characteristic sense of humour, “I had a phone call from a guy who told me my end was near. And I guess that was a bit ambiguous,” he pauses for a second, “It could have meant I was short.”

While he might not welcome the harassment, the attention he gets means that he’s doing something right and “If you’re not doing something worthwhile, you’re not going to get the flak. So, the more flak I got, the more it convinced me that, oh well, something must be working.”

Mind Control

“When most people think of cults, they only think of religious cults,” Haworth explains, “It’s [also] nice to think that there’s a problem elsewhere, like California rather than here.”

There’s also the misconception that only the down-and-out, the mentally ill, and the disenfranchised members of society end up in cults. In reality, cults are looking for the opposite type of person, “They think there must be something wrong with someone that finishes up in a cult in the first place. It’s the blame the victim syndrome,” Haworth adds.

During his own time in a group, he remembers the instructions given to him during his recruiting drives, “When I was recruiting, I was told to stay away from ‘space cadets’, that was the technical terminology used.”

Highly educated students or graduates from prestigious universities like Oxbridge, he says, are high-risk targets for recruitment.

American cult expert Steve Hassan’s website Freedom of Mind defines undue influence (another term for mind control) as “any act of persuasion that overcomes the free will and judgment of another person. People can be unduly influenced by deception, flattery, trickery, coercion, hypnosis, and other techniques.”

The CIC website lists 26 different mind control techniques: hypnosis, limitation of food, and sleep deprivation are all part of the list.

Groups do not need to use all twenty-six techniques to erode a person’s autonomy and encourage compliance; instead, a combination might be used depending on the group, as some people are more receptive to some techniques than others.

“All that varies from one cult to another in terms of the methodology is which combination of techniques that particular group uses,” Haworth describes, “Trance induction, for example, is extremely powerful and if someone is being induced into a trance state through chanting or through hypnosis, then you can do just whatever you want with that person.”

Other experts or specialists may have a different way of identifying the presence of mind control, but Haworth prefers to take a non-academic approach to keep things understandable as “Some criteria are difficult to get your head round. It’s not plain English for me, but then again, I’m from the north of England.”

Psychological Coercion

When asked to define the danger these groups and their leaders pose to the public, Haworth needs little time to think over his answer, “A complete loss of free will, a loss of the ability to think and use logic, which most of us take for granted… And until you see that happen in someone, it’s hard to imagine what that can be like.”

He compares what happens in cults to a type of slavery, but unlike the laws that protect people from being physically trafficked, there’s nothing to protect people from psychological coercion, “What cults have been doing is a form of slavery for decades. And not one of the slavery laws has ever been applied and can’t be applied when dealing with cults.”

Only within the last decade have laws been passed to protect people from coercive and controlling behaviours. The issue is proving the presence of psychological coercion. “It’s not illegal to psychologically coerce people,” Haworth points out.

Section 76 of the Serious Crime Act 2015 makes it an offence to use controlling or coercive behaviours and, if found guilty, carries a maximum penalty of a five-year prison sentence. The law, however, only applies when people are personally connected, which means only in the context of family or relatives, or being in a relationship (intimate, married, or civil partnership). There’s another misconception that a person joins freely and can leave on the same terms.

The signature block at the end of each of Haworth’s emails contains a warning of sorts. It reads, “People don’t join Cults…they are recruited.”

While people may be attracted to cults by their own will, a series of techniques will be used against them to erode their autonomy: keeping them within the group, carrying out orders without question, and behaving in ways that go against their best interests.

“If you get a judge that understands what a cult is, boy you’ve done well.” Haworth gives the example of a family member trying to access their family after they’ve been shunned or lost contact with their loved ones, which is, unfortunately, a frequent occurrence when people are involved with cults.

The judge may say to a desperate husband trying to contact his wife, “‘Please, Sir. Are you trying to tell me that your spouse is a cult member? How ridiculous! Your spouse is a very intelligent person.’ So, this person is equating intelligence with sussing out of cult ahead of time and being less likely to be recruited. It’s actually just the opposite.”

If it’s not illegal to set up a cult and psychologically coerce people into working for free, handing over their belongings and finances, and excommunicating their friends and family, then one of the best defences someone has in ensuring they’re not recruited is to research the group thoroughly before making any type of commitment.

“If it’s that good, then there must be a ton of information available ahead of time. Check it out thoroughly. If it’s okay, you should be able to Google it and find a lot of good news online. But Google it, in case it’s a cult,” recommends Haworth, “because if it is, there may well be some horror stories online.”

He adds, “More people will check out a second-hand car than a course that might ruin their lives.”

Role Change

I scheduled another phone call with Haworth, and we exchanged emails in the week leading up to our next conversation.

“Never heard of you,” he tells me with a laugh when I inform him who is calling.

Today will be the last time Haworth answers the phone at the CIC.

We’re discussing his involvement in the Canadian group when he suddenly stops me mid-question because he’s remembered something. It sounds as if he’s about to say, “If I have one regret,” but he self-corrects, and asks me if I remember the story about his Canadian neighbour who gave him the newspaper article about the group he was involved in all those years ago.

I should have gone back to her to say thank you so much. Maybe bought a bunch of flowers or something. But I never saw her again. She left the country and went to live elsewhere. So that’s a little regret that I have, that I could ever thank her for being so kind to give me the newspaper article… She said [the article] was great, because [from] her perspective it was, because she was worried about me.

I ask if anything shocks or surprises him after all this time. Haworth needs no time to think over his answer:

It’s not what shocks me, it’s what upsets me. It upsets me that the government still doesn’t understand how cults work and aren’t doing anything to protect British citizens. And because of that British money is going down the drain into these groups. British corporations are less productive than they could be. The National Health Service is hit with more patients.

Haworth’s previously jocular tone is absent:

It upsets me that the legal system is, by and large, completely unaware of how cults operate and how undue influence should be applied in civil cases. It upsets me that the police haven’t been trained in this area. It upsets me every time the phone rings and someone else has been lost to a cult.

But not every phone call is just another horror story, another desperate parent or spouse seeking advice about how to get their loved ones back.

Sometimes, it’s a person who’s escaped from a group, or it’s people recently reunited with their family members, and they want to wish Haworth a happy Christmas:

It makes my day when I get a call from somebody who says they’ve just managed to escape even if they’re at the beginning of the withdrawal period, which is an awful time to go through. I’ll say, ‘Hey, thanks very much, you’ve made my day, you really have’. And it’s such great news because most of the time it’s another person grieving the loss of someone to one of these groups.

But even after forty-five years in the field and everything he’s seen, Haworth is not considering today as the start of a type of retirement.

The phone calls at the CIC will stop after today, but Haworth has no intentions of leaving the field. Instead, he’ll be focusing more on maintaining the CIC’s online presence, writing on the topic, and recording the occasional podcast, “I’m going behind the scenes,” he explains, “I’ll still be out there and trying to warn people but doing it through writing rather than in person on the phone.”

“And,” he tells me, “My wife will come first.”

Author’s Note: The names of any cults or groups Mr Haworth has personally been involved with, or encountered in the courtrooms, have been omitted from the following article.

If you, or anybody you know, have been affected by anything mentioned in this article and would like more information or support, please visit one of the following websites:

- Dare to Doubt –https://www.daretodoubt.org/home

- Dr Alexander Stein – https://www.alexandrastein.com/

- Dr Janja Lalich – https://janjalalich.com/

- Dr Gillie Jenkinson – https://www.hopevalleycounselling.com/about

- EnCourage – http://www.encourage-cult-survivors.org/

- Faith to Faithless – https://www.faithtofaithless.com/

- The International Cultic Studies Association – https://www.icsahome.com/