Have you seen the new hugely successful/box office bomb (delete as necessary) Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny? I haven’t, but then again if I wanted to watch an old man riding a horse down St Vincent St, I’d just pop over to Glasgow Skeptics.

In the film, as in all the others in the franchise, there is a MacGuffin to drive the plot along. In this case, it is the Dial of Destiny, aka Antikythera mechanism, sometimes referred to as the Archimedes dial. The previous films’ plot devices ranged from the Biblical Ark of the Covenant and the Holy Grail, to The Hindu Shankara stones and, in the fourth (and by far the worst) movie, Mayan crystal skulls.

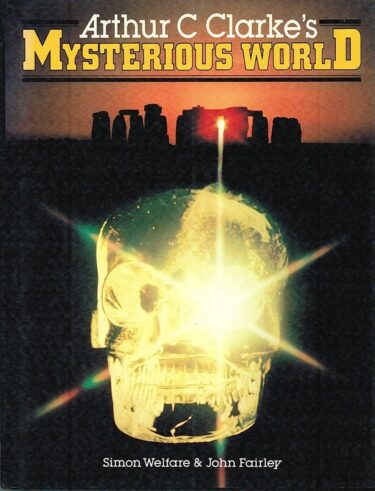

I think we can safely ignore the ridiculous movie plot depicting the crystal skull as the head of a literal glass-boned skeletal alien waiting to be reunited with its body, so it and its companions can return to their home planet. But this film’s MacGuffin is at least a real phenomenon. Strange crystal skulls do exist – Arthur C. Clarke used one to represent his Mysterious World TV show and subsequent book, and many believe them to have supernatural powers, or at the very that they prove neolithic native Meso-Americans had some incredible and unknown ability to fashion glass, but not metals.

But where do these objects come from? How were they made? And what do they tell us about their maker?

The real Indiana Jones?

Let me introduce you to Mr Frederick Albert (F.A.) Mitchell-Hedges (1882-1959), as it was he who first brought a crystal skull (the one featured on the cover of Clarke’s book) to the attention of the wider public. A seasoned traveller and self-proclaimed adventurer, Mitchell-Hedges had a radio show in 1930’s New York, where he regaled his audience with tales of escaping from “native savages” or wild jungle animals in dramatic fashion, when searching for lost civilisations. A proto-Indiana Jones in many ways.

In 1954, he published the modestly titled book Danger My Ally, detailing his ‘True-life adventures’ exploring lost-cities and lost-worlds. In the chapter The Skull of Doom and a Bomb he reveals that his daughter, Anna, was in possession of a crystal skull that she had found 30 years before in the jungles of Belize when she had accompanied her father exploring the Mayan ruin of Lubaantun. Mitchell-Hedges senior concluded that the skull was over 3,600 years old, and that it was used by Maya priests to strike people dead by the force of their own will. But, he added, “It has been described as the embodiment of all evil. I do not wish to try and explain this phenomena.” [sic]

Several other skulls have been identified around the world. There is one in the British Museum which they describe as:

Purchased from Tiffany of New York in the late 1890s, the skull had passed through many hands and was said by G. F. Kunz in 1890 to have originally been brought from Mexico by a Spanish officer ‘sometime before the French occupation of Mexico’ [1860].

Another was sent to the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. anonymously in 1992 and the accompanying letter said it was part of an 19thC Mexican general’s collection of ancient Mayan artefacts. A third is in the Musee De L’Homme in Paris, and a further 9 are in private hands.

There are modern reproductions. However, it is generally accepted there are twelve surviving Mayan skulls. Innumerable legends have grown up, usually about thirteen such skulls being gathered together in a Mayan temple to complete some sort of task – often to save humanity, or affect the Mayans’ enemies, or similar.

The objects are a perfect synthesis of numerous pseudosciences: they are made from a single quartz crystal with all the woo associated with crystals, they are representative of a little-known and mysterious ancient culture who could seemingly do things we cannot now do, and of course, they are human-like skulls – they look freaky. All of this gives them a prominence that most archaeological objects would never normally obtain.

Maya Mackems

But, how on earth did the ancient Mayans make them?

The truth, of course, is that they didn’t.

Tellingly, no skull has ever been found in any official or academically driven excavation in Mexico or elsewhere in Central America. Indeed, in December 1943, F.A. Mitchell-Hedges disclosed in a letter to his brother that he had purchased the skull (the one he says his daughter found in the 1920’s) from London art-dealer Sydney Burney, for £400. Despite this, right up to her death in her 90’s, Anna Mitchell-Hedges continued to claim that the skull was found by her in Belize when she was a child.

Analysis of the British Museum skull and other examples show that the quartz itself is chemically identical to natural crystals found in southern Brazil – a distance that would not have been insurmountable for Central Americans, but a highly unlikely location, given that no trade route has ever been identified over that sort of distance in that period.

The same analysis found that using traditional tools and resources available in pre-Columbus America would have taken over 150 years constant work to have sanded quartz into such a smooth finish. However, the skulls themselves showed marks consistent with post-industrial rotary power tools.

Mexi-con

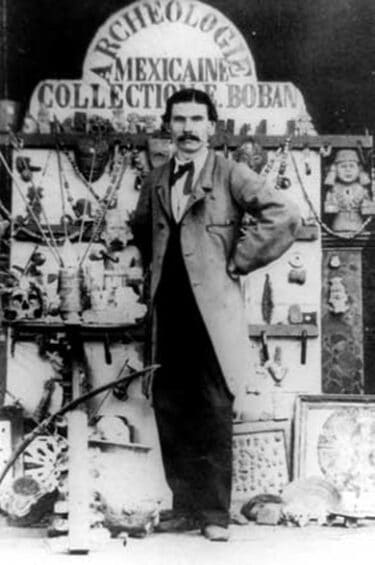

In 1870’s France, an antiquarian called Eugene Boban was commissioned by Napoleon III to collect Aztec and other native American artifacts for display in Paris. He travelled to Central America in search of objects for his Emperor, and after his return opened a shop in the French capital, called Antiquites Mexicaines, specialising in Meso-American objects. He later moved his business to New York via Mexico City, and was responsible at the very least for the British Museum and the Parisian Musee sales. In all likelihood, he was responsible for selling many of the skulls to the wider public.

Boban had collected innumerable objects over the years spent in Mexico, and when he left for France with his haul, his friend sent him a bon voyage letter, adding:

Flood France with your curiosities, and squeeze all the ugly metal out of them that you can in exchange …

Unfortunately, not long after his shop had opened, the Prussian army laid siege to Paris and that was soon followed by the Commune Revolt. It would be several years before he made a major sale.

Southern Brazil, where the quartz comes from, has a large immigrant German population. Many emigrated there in the mid-19th Century, a few from the little Rhineland town of Idar-Oberstein where they took with them their professional and long-standing skills of gemstone cutting. They retained close links with the town of their birth and sent several examples of quartz and other gems back to Germany to see what the skilled artisans could make of them.

They fashioned the quartz into skulls. Most likely as an object for marketing the skills of the cutters in turning a lump of quartz into a beautiful object. There is good reason to believe that M. Boban later visited the German town (just a few miles over the French border) and purchased some or all the skulls to sell in his old curiosity shop, passing them off as ancient Aztec/Inca artifacts due to the style. It is possible, but cannot be confirmed, that he commissioned the objects and asked for them in the style fashionable at the time, following recent European involvement in Mexico.

Dismissed as novelties in museums, they were largely forgotten about until Mitchell-Hedges claimed the one he had bought from an art-dealer was a mysterious Mayan object with an evil history found by a young girl in a lost-city. From there the skulls became more well known to the wider public and took on supernatural connotations thanks to a continuous stream of “believe-it-or-not” books and magazine articles.

There is no doubt they are interesting curiosities and excellent examples of the gem-cutting skills found in 19thC Idar-Oberstein but ancient Meso-American objects with supernatural powers they almost certainly are not.