It has been widely reported that, in order not to jeopardise our trade deal with India, Boris Johnson failed to close the border quick enough for preventing the delta variant entering Britain. The consequences were devastating. Now our government is about to please Modi again. The “2030 Roadmap for India-UK future relations” is a policy document of the UK government. In it, we find that the UK government intends to:

Explore cooperation on research into Ayurveda and promote yoga in the UK. Increase opportunities for generic medicine supply from India to the UK by seeking access for Indian pharma products to the NHS and recognition of Indian generic and Ayurvedic medicines that meet UK regulatory standards.

This begs the question, are these plans good or bad for UK public health?

Ayurveda is a system of healthcare developed in India around the mid-first millennium BCE. Ayurvedic medicine involves a range of techniques, including meditation, physical exercises, nutrition, relaxation, massage, and medication. Ayurvedic medicine thrives for balance and claims that the suppression of natural urges leads to illness. Emphasis is placed on moderation. Ayurvedic medicines are extremely varied. They usually are mixtures of multiple ingredients and can consist of plants, animal products, and minerals.

Relatively few studies of Ayurvedic remedies exist and most are methodologically weak. A Cochrane review, for instance, concluded that

although there were significant glucose-lowering effects with the use of some herbal mixtures, due to methodological deficiencies and small sample sizes we are unable to draw any definite conclusions regarding their efficacy. Though no significant adverse events were reported, there is insufficient evidence at present to recommend the use of these interventions in routine clinical practice and further studies are needed.

The efficacy of Ayurvedic remedies obviously depends on the exact nature of the ingredients. Generalizations are therefore problematic. Promising findings exist for a relatively small number of ingredients, including Boswellia, Frankincense, Andrographis paniculata. Caution is, however, indicated: Ayurvedic remedies often contain toxic substances, such as heavy metals which are deliberately added in the ancient belief that they can have positive health effects. The truth, however, is that they can cause serious adverse effects.

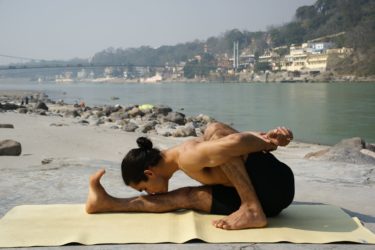

Yoga has been defined in several different ways in the various Indian philosophical and religious traditions. From the perspective of alternative medicine, it is a practice of gentle stretching exercises, breathing control, meditation, and lifestyles. The aim is to strengthen ‘prana’, the vital force as understood in traditional Indian medicine. Thus, it is claimed to be helpful for most conditions affecting mankind. Most people who practice yoga in the West practise ‘Hatha yoga’, which includes postural exercises (asanas), breath control (pranayama), and meditation (dhyana). It is claimed that these techniques bring an individual to a state of perfect health, stillness, and heightened awareness. Other alleged benefits of regular yoga practice include suppleness, muscular strength, feelings of well-being, reduction of sympathetic drive, pain control, and longevity. Yogic breathing exercises are said to reduce muscular spasms, expand available lung capacity and thus alleviate the symptoms of asthma and other respiratory conditions.

There have been numerous clinical trials of various yoga techniques. They tend to suffer from poor study design and incomplete reporting. Their results are therefore not always reliable. Several systematic reviews have summarised the findings of these studies. An overview included 21 systematic reviews relating to a wide range of conditions. Nine systematic reviews arrived at positive conclusions, but many were associated with a high risk of bias. Unanimously positive evidence emerged only for depression and cardiovascular risk reduction (Ernst E, Lee MS: Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies Volume 15(4) December 2010 274–27).

Yoga is generally considered to be safe. However, the only large-scale survey specifically addressing the question of adverse effects found that:

approximately 30% of yoga class attendees had experienced some type of adverse event. Although the majority had mild symptoms, the survey results indicated that attendees with chronic diseases were more likely to experience adverse events associated with their disease. Therefore, special attention is necessary when yoga is introduced to patients with stress-related, chronic diseases.

So, should we be pleased about the UK government’s plan to promote Ayurveda and yoga? In view of the mixed and inconclusive evidence, I feel that a cautious approach would be needed. Research into these subjects could be a good idea, particularly if it were aimed at finding out what the exact risks are. Whole-sale integration does not, however, seem prudent at this stage.

In other words, it would be wise to first find out what generates more good than harm for which conditions and subsequently consider adopting those elements that fulfil this vital criterium. Yet, I doubt that things will pan out like this. More likely, political interests will again outweigh scientific caution. I just hope that the consequences are not as bad as the failure to close our borders in time.