“It was red,” she recounted, “And it was staring unblinkingly at her with a hypnotic intensity.” A primordial fear had crept up her spine, but she stood riveted. Then, images of satanic worshippers engaged in a sacrificial procession flashed before her eyes.

“Let us in,” she recalled a monotone chanting filling her ears as she froze deeper in its hypnotic gaze. “Let us in,” a familiar deep baritone echoed, directing her gaze upwards to a young man’s fair face. Confused, she shifted her gaze downwards and realised that she had been staring at the ominous tattoo of a single red eye etched on his right forearm.

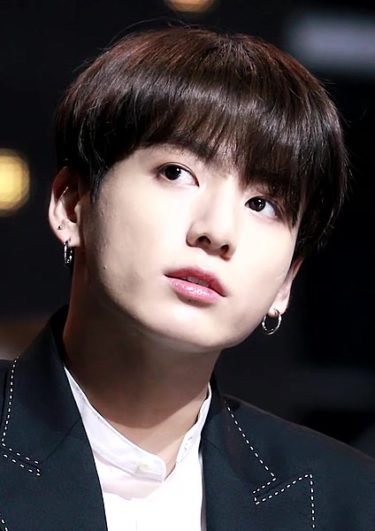

She screamed, before waking from this haunting dream about BTS member Jungkook. The mother of two rushed across her quiet Singapore apartment to warn her second daughter of what she believed to be a God-sent warning about the malicious intentions of the latter’s favourite boy band.

Is BTS a part of the Illuminati?

“Yes, BTS is a part of the Illuminati,” 19-year-old ex-BTS fan Lydia Pan told me, before recounting her Christian mother’s ominous vision. I spoke to Lydia in order to understand more about the conspiracy theory linking the world’s hottest boy band to the infamous Illuminati.

Lydia recalled her days as an ARMY (for those unfamiliar, a title BTS fans take on), which began in as early as 2016, before explaining her later decision to leave the fandom.

“As a young Christian, I couldn’t in good faith continue to support them,” Lydia said. “It wasn’t easy, but my mother and sister helped me through prayer. And now I’m free.”

Her mother’s ‘prescience’ was not the only damning evidence for Lydia. Her fears were first aroused by what appeared to be multiple instances of unholy themes in the works of the global music phenomenon. It was the same for many other BTS fans who came to suspect ties between the idol group and the Illuminati – an elusive historical group of scholars which, as we know in modern day, has somehow become the subject of a conspiracy theory alleging they are a Satanist cult in control of the world.

Biblical references, dark themes and fan suspicions

Scouring through multiple online accounts, the most common evidence cited by those who believe BTS are part of the Illuminati include suspicious symbolism in the music videos for the songs ‘Blood, Sweat & Tears’, ‘Boy Meets Evil’, and ‘ON’.

The music video for ‘Blood, Sweat & Tears’, a song about temptation, is set in what appears to be a European art museum. Strikingly, it features scenes showcasing a replica of Michelangelo’s Pieta. Later in the film, we see witness the face of Mary, who is cradling a faceless Jesus, shatter after a scene in which BTS vocalist Jin kisses a statue with black wings.

“It’s symbolic of how Judas betrayed Jesus with a kiss,” Lydia explained. She, along with other fans, came to this conclusion in the context of an earlier part of the video where BTS members are seen seated at a table, in what can reasonably be interpreted as a reference to the Last Supper.

The religious references don’t end there. Believers claim that most of BTS’ videos since their ‘Wings’ album feature dark, Mephistophelian overtones.

“[In] ‘Boy Meets Evil’, [their rapper] J-Hope tells the listener about the euphoria of living in sin, and how he shook hands with the devil. Plus, the music video for ‘ON’ has apocalyptic themes,” Lydia told me, before calling attention to the video’s depiction of rapper RM standing before Noah’s Ark, and another scene where Jungkook’s hands are bound with what resembled a crown of thorns. To theorists, these appeared to hint at a desire to be free and to reset the world, in parallel to what conspiracy theorists have claimed to be the modern Illuminati’s goals: destruction of ruling institutions and the creation of the New World Order.

Indeed, upon review of the highlighted videos, it was hard to miss the idol group’s liberal use of biblical imagery and references. But it appeared to me that an important question to ask was whether this truly hinted at behind-the-scenes cult activities, or if this just a case of glib behaviour towards scriptural concepts, over-extrapolated by those scouring for evidence of the unholy.

This question is not unique to BTS: use of Christian iconography and themes is prevalent in the K-Pop industry, just as it is common in Western pop culture, too. This may explain the Western origins of conspiracy theories linking celebrities to Satanic behaviour.

Western pop culture paranoia dates back to as early as the 60s

Pop culture conspiracy theories in the West can be traced as early as the 1960s and 1970s – an era that witnessed many denouncing rock-and-roll as “the devil’s music”. This has been attributed to how the core values of ‘change’ and ‘rebellion’ guided the genre. A reflection of the social zeitgeist of the times, it supported a movement that entailed rebellion against prevailing moral authorities, which were largely grounded in traditional Christian values and beliefs.

On the topic of morally controversial lyrics and general content, the Western music industry has evolved to sensationalise what would be considered as “sinful” behaviour to create shock value in the tracks and videos that it puts out. In the name of standing out in what is now an extremely saturated industry, creators have resorted to religious appropriation of Christian symbolism.

From Lady Gaga’s controversial ‘Judas’ release in 2011, to Lil Nas X’s ‘MONTERO’ a decade later, these persistent accusations of anti-Christian behaviour among celebrities are definitely far from surprising.

Another common reason for religion-driven condemnation of pop culture is the fanatic behaviour that it encourages. Many religious leaders have been quick to label consumption of pop music as distractions from more holy pursuits, believing that as fans devote more time and energy into obsessing over pop icons, less time is left for spiritual worship, introspection, and congregation.

Markedly, much of contemporary conspiracy theory is characterised by the Illuminati paranoia – essentially suggestion that anyone who is famous owes their fame to the power of a secret cabal. This likely has roots in the age-old tale of Faust, who famously sold his soul to the devil to achieve worldly ambitions – a bargain that was later echoed in mythology around Blues musicians like Robert Johnson.

Pop culture conspiracy theory takes root in Asia

Returning to BTS, it is certainly curious to see how Eastern fans have somehow taken these Western concepts and applied them to figures in Korean entertainment. BTS are far from the only recipient of Illuminati-related accusations, with similar theories targeting other artists sprouting as early as a decade ago.

We can perhaps chalk this phenomenon up to globalisation, and the entailing bilateral diffusion of culture. In recent years, we’ve seen the ‘Hallyu Wave’ gather incredible momentum, as the number and spread of K-Pop fans increased on a global scale. But before the spread of K-Pop, most international pop culture enthusiasts were first exposed to Western pop culture and were already around to witness the explosion of theories alleging links between the secret society and the likes of Beyoncé and Lady Gaga. Such was the case for my interviewee, Lydia.

For these fans, it was perhaps as simple as taking these same ideas and drawing links to it and the Asian music scene. After all, as Lydia reasoned, “it would make sense for such a powerful organisation to be able to expand its reach to the other side of the globe”.

Further, while Eastern cultures differ from Western cultures in many ways, there are cultural universals which enabled these theories to take root in Asian society. While it’s clear how these ideas made sense to the large Christian populations across the continent, it is interesting to observe how they also spread to some predominantly Muslim regions, perhaps due to the existence of ‘demons’ (or ‘shaitan’) in Islamic narratives. This is may be why a Malaysian preacher made headlines in 2019 for denouncing BTS members as “demonic” and calling upon the cancellation of their concerts locally.

Same old story, different place, slightly different outcome

I was also curious about how differently these theories were received in the East, where the large corporations behind K-Pop have manufactured their idol’s images and the media consumption process in a way that breeds a problematic fan culture marked by obsessive behaviour. Lydia recalled that one of the other reasons that compelled her to leave the BTS fandom was that it led her to be “distracted from God and [her] studies.”

She explained that participation in the fandom as a “proper fan” typically entailed rearranging one’s schedule around performance livestreams, going onto social media to ask people to stream the group’s songs to improve music chart rankings, and regular (sometimes multiple) purchases of their newly released albums. She also participated in daily discussions with fellow fans on forums. Lydia found excitement in the fandom’s interactivity, but eventually found it to be unhealthily time-consuming, especially with the dedication that she felt was expected.

But this was just the tip of the iceberg, as cases of extreme fanaticism has become such a large problem in the Korean entertainment sphere. The term ‘sasaeng’ was coined to refer to individuals who resort to borderline criminal acts to interact with their idols.

“You see, that’s the problem with BTS. I read online that they’re designed to lead you astray to worship false gods. Because that’s what K-Pop is actually about – idols and idolatry,” Lydia told me, “I could no longer let them control so much of my life. I could no longer allow them to try and control my mind. Because that’s what they want, isn’t it?”

I also imagine that the theory of BTS surrendering their moral integrity to the Illuminati for fame would perhaps be better received in Asia. After all, they had reached unprecedented levels of fame, especially among their industry peers.

While many other hopefuls had attempted to break into the Western market for the past decade, BTS made history by being the first K-Pop group to crack the top 40 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in 2017. Four years later, the group continues to thrive in the Western market.

While many conspiracy theorists have attributed this success to the work of the Illuminati, industry experts believe it is much more a testament to the skilful manufacturing of the members’ images and branding. The seven are said to be modelled after Carl Jung’s classic archetypes – making the boys formulaically relatable and hence greatly marketable.

This perhaps also explains the casual use of Christian imagery in K-Pop music. In some ways, K-Pop’s attitude towards this is more relaxed due to the secular leanings of their home market. More than 50% of Koreans report to have no religious affiliations. This has likely allowed local music giants to be less wary of stepping on toes when depicting biblical references in their artistic work.

In fact, it seems that these artists view the concepts of ‘devils’ and ‘fallen angels’ as rather romantic and sexy. Beyond BTS, many other idol groups have made comparisons between these creatures and toxic lovers or ex partners. We see the same being done by Shinee in their hit ‘Lucifer’, and by girl group SNSD in their release of ‘Run Devil Run’.

American influence in Korea’s democratisation has also led to the use of the English language (explaining the random use of English in K-Pop songs), and familiarisation with Western concepts (explaining the use of European art and scriptural references), as being seen as markers of education and sophistication. To an English native, this may be akin to being fluent in French and being well-versed in Italian paintings.

Not the anti-Christ, but perhaps un-Christian

To conclude, it seems that it’s hard to deny the very un-Christian (and almost blasphemous) symbolism and references in BTS and K-Pop productions. However, there are far more plausible reasons behind the use of these symbols than it being the goal of an enlightened cult’s world domination. I can understand why people like Lydia have come to see these themes as proof of links to the Illuminati, but for the rest of us, we can remain skeptical.

I asked Lydia what she thought about these alternate explanations of the use of symbolism. With knitted brows, she contemplated the question for a moment before relaxing into some semblance of agreement.

“However,” she tutted, “I still believe that their artistic concepts can be seen as wholly disrespectful to what is held as sacred among Christians. Creating art does not have to resort to belittling revered beliefs.”

It seems that we can come to two conclusions here.

Firstly, BTS is probably not anti-Christian, but they are perhaps un-Christian. And Secondly, given the K-Pop industry’s notorious commodification of their idols, they have probably sold their souls, albeit figuratively – not to Lucifer, but to their record label.