This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 19, Issue 1, from 2006.

Given that the majority of smashed windscreens on the Portsmouth Road are likely to have been caused by loose road chippings, how is it that something so inoffensive could lead to a national mystery?

We believe that there are two crucial factors in the origins and level of interest in the phantom sniper incidents. These are: (1) the volume of traffic along the Portsmouth Road and (2) the campaigning nature of the Esher News and Advertiser.

When visiting modern-day Esher, one is immediately struck by how dominant the Portsmouth Road is within the village. This road is one of the main trunk routes from London to the south coast and it cuts through the middle of the village. Even now, years after the building of the Esher bypass road, it carries a massive volume of traffic along it creating much noise and congestion.

At the time of the sniper incidents there was a great deal of concern in Esher about the level of traffic running through the village and of the number of accidents this was generating. Practically every issue of the ENA was dominated by articles about the road. Each issue would carry several items concerning that week’s traffic accidents and each month there would be a tally of accidents in comparison with the previous month. Throughout the entire span of the phantom sniper the ENA showed extreme concern at what the traffic was doing to the village and was actively involved in the local campaign for a bypass road to be built.

Given that the Portsmouth Road was then the busiest highway in Britain (see The Skeptic, 18.4, Part Two) it is no wonder that traffic would be high on the list of concerns of locals and the council alike. This local obsession with traffic may have laid the foundations for the phantom sniper.

It is probably no coincidence that the first acknowledged shooting was a very high profile one involving the celebrity journalist Richard Dimbleby, who reported his broken windscreen to the Esher police. This would have made both local people and the ENA aware of the idea that there was a sharp shooter abroad on the Portsmouth Road. As further reports of smashed windscreens came in, so the ENA assumed that there was a connection between them and promoted the idea of a sniper.

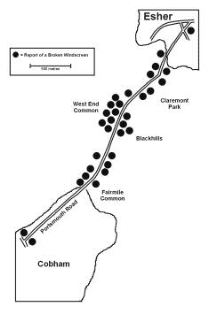

Judging by the number of times that the ENA mentions the Esher Police Station, it would appear that the newspaper was getting most of its reports from a contact inside the Esher police station. This would explain not only how the ENA got to hear of so many broken windscreens but also why the incidents are so tightly clustered on the road between Esher and Cobham (see map). Anybody who received a damaged windscreen on this stretch of road, and who thought that they had been shot at, would automatically call in at the nearest police station which would be in either Esher (if heading northbound) or Cobham (southbound). Assuming that there was some communication between the Esher and Cobham police stations, the ENA would get to hear of all such incidents.

It is also noticeable that a good many of the drivers reporting these incidents lived locally. Local drivers who were aware of the sniper rumours would be more likely to report their damaged windscreens to the authorities than passing motorists who might put the incident down to loose stones.

After the start of the second wave of damaged windscreens the ENA started to take an interest not only in the ‘shootings’, but also actively campaign to get them looked at by the authorities. It would appear that this campaigning, which resulted in it carrying 40 articles on the matter in 36 months, caused a mild form of hysteria in which any windscreen damage from anywhere within a 20 kilometre radius around Esher, could get reported. The eventual involvement of the national press, the local council, the Minister for Transport and the Metropolitan Police was seen by the ENA as a vindication of its position on the matter. The editorial of the 20th June 1952 makes it clear that the ENA sees itself as having been crucial in the promotion of this affair, and they are probably correct in this.

Like all bouts of social delusion, there comes a point when the number of incidents peak and interest begins to fall away again. This seems to have been reached in about late September or early October 1952 when after over six months solid coverage the number of reports and news items began to decrease markedly. Although there was the odd burst of interest, the phantom sniper had become yesterday’s news.

The last piece of the puzzle concerns the large number of smashed windscreens on that one small stretch of the Portsmouth Road. By our count at least 43 windscreens were smashed over a 36 month period (this excludes windscreens that were broken outside the Esher area). It was this large number that drew the ENA’s attention in the first place and which helped perpetuate the idea of a local sniper. Is it really feasible that loose stones or structural failure could cause so many breakages in such a short space of time?

Unfortunately, we do not have the police incident books from Esher or Cobham, so it is impossible to know how many reports of windscreen damage they were receiving in the periods before and after the sniper incidents. We also know nothing of the road surface conditions. We do, however, have some other clues.

On average there were one or two windscreens a week being reported to the ENA during the peak period between March and October 1952. According to the traffic census and stone damage data quoted in the last issue, the number of incidents is perfectly within the bounds of normality. The levels of damage do not look excessive when compared with the volume of traffic and the susceptibility of car windscreens to damage from loose stones.

A comparison to other phantom sniper incidents

Given that the scenario outlined above relies on circumstances that are capable of being replicated elsewhere in the world, how does the Esher episode compare to other phantom sniper incidents?

Fort’s Phantom Snipers:

Charles Fort mentions a number of phantom sniper incidents in his book Wild Talents. Most of these concern people who have been shot and the bullet found but not the sniper – these do not concern us here. There are, however, two apparent episodes of mass shootings that interest us that took place in London in April to May 1927 and Camden, New York from November 1927 to February 1928.

An investigation of local London papers revealed that the incidents listed by Fort were totally unconnected to each other and most involved genuine shootings in which real, not phantom, bullets were recovered. Through pressure of time, the New York incidents were not investigated but they superficially would appear to have more in common with the Esher incidents than the 1927 London ones.

The Seattle panic:

During March 1954, police in the city of Bellingham in north-west Washington State were baffled by reports that a ghostly sniper was shooting at car windscreens. The situation soon reached crisis proportions. Over a one-week period in early April over 1,500 windscreens were reported damaged. Despite the massive number of ‘attacks’, police chief William Breuer had no suspects and no tangible evidence. Authorities surmised that the most likely weapon ‘was a BB-gun barrel attached to a compressor in a spark-plug socket, fired from a moving car’.

At the height of the episode, people across the city of 34,000 placed various items, from newspapers to door masts and even plywood, over their windscreens for protection. Meanwhile, downtown parking garages were under heavy security. The phantom pellet-shooter seemed to be everywhere; even police cars reported being struck. In lieu of a lack of evidence for vandals, by mid-April local and national media began emphasising the mysterious nature of the damage. On April 12, a reporter for Life Magazine came to Bellingham and referred to the episode as ‘ghostly’ and the perpetrators as ‘phantom’-like. The next evening, the Seattle Times talked about ‘elusive BB-snipers’. In time, reports of the mysterious windscreen attacks moved closer to Seattle, Washington, 80 miles to the south. Reports of strange pit marks on windscreens first reached Seattle on the evening of April 14, and by the end of the next day, weary police had answered 242 phone calls from concerned residents reporting tiny pit marks on over 3,000 vehicles. In some cases, whole parking lots were reportedly affected. The reports quickly declined and ceased. On April 16 police logged 46 pitting claims, and 10 on the 17th, after which no more reports were received.

Nahum Medalia of the Georgia Institute of Technology and Otto Larsen of the University of Washington studied the episode. They stated that the most common damage report involved claims that tiny pit marks grew into dime-sized bubbles embedded within the glass, leading to a folk theory that sand flea eggs had somehow been deposited in the glass and later hatched. The sudden presence of the ‘pits’ created widespread anxiety as they were typically attributed to atomic fallout from hydrogen-bomb tests that had been recently conducted in the Pacific and received saturation media publicity. At the height of the incident on the night of April 15, the Seattle mayor even sought emergency assistance from US President Dwight Eisenhower.

In the wake of rumours such as the existence of radioactive fallout, and by a few initial cases amplified in the media, residents began looking at, instead of through, their windscreens. An analysis of the mysterious black, sooty grains that dotted many Seattle windscreens was carried out at the Environmental Research Laboratory at the University of Washington. The material was identified as cenospheres – tiny particles produced by the incomplete combustion of bituminous coal. The particles had been a common feature of everyday life in Seattle, and could not pit or penetrate windscreens.

Medalia and Larsen noted that as the pitting reports coincided with the H-bomb tests, media publicity on the windscreen damage seems to have reduced tension about the possible consequences of the bomb tests. Secondly, the very act of phoning police and appeals by the Mayor to the Governor and even President of the United States “served to give people the sense that they were ‘doing something’ about the danger that threatened”.

Although on a shorter time scale, the Seattle panic has clear similarities to the Esher one and is undoubtedly the best studied comparison that we could find.

Glasspox:

Three articles from 1950s editions of FATE magazine cover smashed windscreen incidents and refer to these epidemics as being due to ‘glasspox’. According to FATE, ‘glasspox’ was apparently a very common phenomenon in the 1950s. They make mention of mass windscreen damage in Pittsburgh and Rome as well as carrying several individual accounts from readers. Theories cited include sonic booms, a reaction to windscreen cleaning fluids, radioactivity, and even microscopic organisms attacking the glass! One reader even asked an Ouija board about the cause of glasspox; the ‘spirit’ placed the blame on airborne ‘bantom ash from radium deposits’.

Miscellaneous others:

Frank Edwards, in his book Stranger than Science, which carries a brief report on the Esher incidents, notes that ‘…in June of 1952, State police in both Indiana and Illinois found themselves chasing a phantom gunman who was fully as elusive as the one in England’. Attempts were not made to find these incidents although it is probable that Edwards heard of these through his connection with FATE magazine, as was the case with the Esher incidents.

And finally…

The search through four years’ worth of the ENA produced one other item of interest. This concerns two UFO sightings that were reported in the ENA, both of which are extremely tame in comparison to today’s surgically obsessed extraterrestrials. We can only agree with the author of a letter to the ENA who says of the UFO: “It is a pity that your eyewitness did not notice which side of the road the object flew along so that we might have gathered whether the aircraft was British or Continental?”

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank staff at the Esher Library, British Newspaper Library, D M S Watson Science Library, Automobile Association, The Esher News and FATE Magazine.