This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 15, Issue 2, from 2002.

The camera cannot lie – or can it? From the mid-Victorian era to the 1920s, thousands of people were hoaxed by photos which supposedly proved the existence of ghosts. A fascinating selection of such photographs has been put online by the American Museum of Photography.

Unscrupulous photographers made large sums of money by producing photographs of sitters accompanied by other-worldly “spirits”. These “spirits” were usually supposed to be the ghosts of the sitter’s recently deceased friends or relatives. Desperate for some reassurance of life after death, the bereaved sitters were unlikely to question the result.

The first spirit photographer was American William H Mumler of Boston, who produced hundreds of photos during the 1860s. Many of his victims had lost sons, fathers, brothers or husbands in the American Civil War and were desperate for consolation. One of Mumler’s most vocal opponents was circus impresario PT Barnum. He condemned Mumler as a fraud, and pointed out that the unscrupulous photographer was exploiting the vulnerability of people whose judgement was clouded by grief. Barnum gave evidence at Mumler’s trial for fraud in May 1869. Mumler was charged with having “swindled many credulous persons, leading them to believe it is possible to photograph the immaterial forms of their departed friends”. To show how easy it was to fake a spirit photo, Barnum and a photographer friend, Abraham Bogardus, produced a photo which appeared to show Barnum with the ghost of Abraham Lincoln.

Spirit photos were easy to fake. Popular knowledge of photography was limited at this time, and most people did not know that such pictures could be produced by a simple double exposure. Another method was even simpler. In this era, exposures of up to a minute were needed for photographs. So, while the subject was sitting still and gazing at the camera, the photographer’s assistant, dressed in suitably ghostly robes, would step into the picture and stand behind them, moving gently so as to create a “ghostly” blur which would render his or her features less recognisable. Alternatively, a dummy could be put into place behind them, and revealed by pulling back a curtain. Other methods involved tampering with the photographic plate during processing.

Mumler narrowly escaped conviction when the judge reluctantly decided that there was insufficient evidence against him. Others were not so fortunate. In Paris, Édouard Buguet and his associate M. Leymarie were imprisoned in 1875 after investigators discovered the dummies and cardboard cut-outs which they used to create “spirits” for their photographs.

Spirit photography enjoyed a revival in Britain after the First World War. One of the best-known spirit photographers, William Hope, took over 2,500 spirit photographs before being exposed as a fraud by Harry Price of the University of London Council for Psychical Investigation. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle tried to rescue Hope’s reputation in his 1922 publication The Case for Spirit Photography. This book is lavishly illustrated with spirit photographs which Doyle felt proved his case. To the modern reader, these appear to be simple double exposures, but knowledge of the technical aspects of photography was less common in the 1920s, and many people appear to have been convinced by Hope and others of his kind.

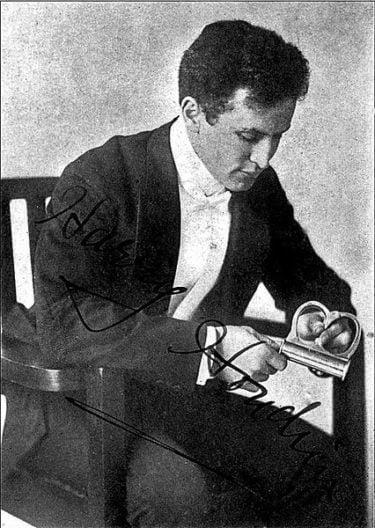

Magicians such as Harry Houdini were indefatigable in their quest to expose such frauds. In 1922, the popular press gleefully reported the exposure of two fraudulent “spirit photographers” by a body of professional magicians: the Occult Committee of the Magic Circle. This body specialised in investigating the claims of self-styled mediums and psychics, many of whom used magician’s tricks to fool people into thinking they had supernatural powers.

One of the most notorious post-war cases was that of spirit photographer Ada Emma Deane. On Armistice Day 1924 she produced a remarkable photograph which appeared to show the spirits of dead soldiers hovering over the Cenotaph in Whitehall. The photo was published in the Daily Sketch, which asked whether any of its readers recognised the faces in the photo. Unfortunately for Deane, many of them did. The “spirits” were not dead soldiers but living footballers and boxers, copied from other photographs. The furious Sketch condemned Deane’s “clear intention … to play upon the feelings of unhappy people who had lost sons in the war”. It challenged her to produce a genuine photo under test conditions, offering her a reward of £1,000 if she was successful. Deane refused the challenge, giving the Sketch ample justification to proclaim her “a Charlatan and a Fraud”.

Spirit photography continued well into the late twentieth century. One incredible photo (reproduced to accompany an article by Matthew Sweet in The Independent on Sunday last year) shows Conan Doyle’s face apparently materialising in the middle of a blob of repulsive ectoplasm which is emerging from a medium’s nose. As Sweet comments, such “supernatural elements now telegraph their paste-and-paper fraudulence”. But to many people at the time they appeared to be proof of what they desperately wished to believe – that their loved ones had some kind of life after death.

Modern writers are rightly skeptical about spirit photographs. But spirit photography still exists, albeit in a slightly different form. Not long ago I visited a New Age fair where an enterprising photographer offered to take a photo of my aura for an extortionate fee. She seemed surprised when I declined the kind offer. But maybe spirit photography will soon be superseded by more modern technology. A recent UK television documentary featured a medium who claimed to be able to contact the dead via the internet. Now there’s a terrifying thought. Imagine being bombarded with junk email from beyond the grave!

References

- Harper’s Weekly, 8 May 1869, p 289.

- Harry Price: Confessions of a Ghost Hunter (London: Putnam, 1936), p 169.

- Arthur Conan Doyle et al: The Case for Spirit Photography (London: Hutchinson, 1922).

- See, for example, News of the World, 14 May 1922, p 12.

- Daily Sketch 13 November 1924, p 10.

- Daily Sketch 15 November 1924, pp 1, 2 and 15.

- Daily Sketch 17 November 1924, p 13.

- Daily Sketch 19 November 1924, p 2.

- Daily Sketch 21 November 1924, p 1.

- Daily Sketch 21 November 1924, p 2. An account of the Deane fraud is also given by Harry Price in Confessions of a Ghost Hunter.

- Matthew Sweet: “They Saw Dead People” in The Independent on Sunday magazine, 23 December 2001. pp 18-21.

- See for example, Fred Gettings: Ghosts in Photographs, The Extraordinary Story of Spirit Photography (New York: Harmony Books, 1978).