There is no question about COVID-19 being the hottest topic on every skeptic’s mind currently, but it isn’t the only pseudoscience out there. This month, I would like to explore the issues faced by European skeptic groups before and during COVID.

The issues are grouped into categories, which, as you will see, can be overlapping, and boil down to what I believe is at the crux of all the issues: quality education.

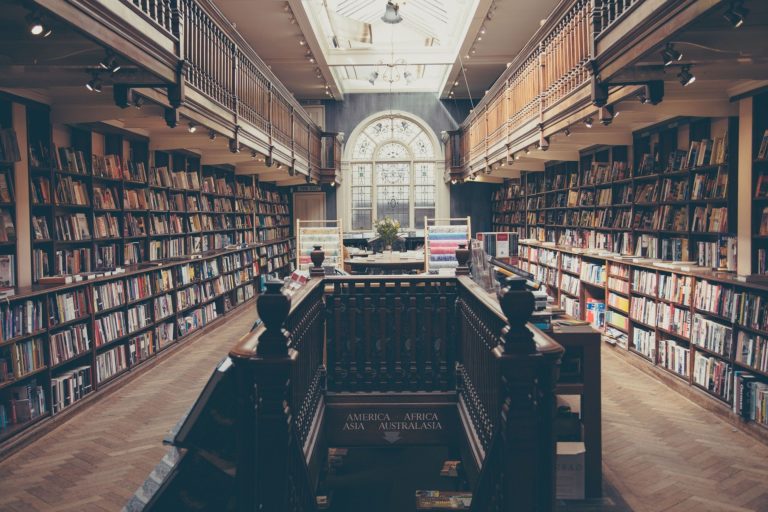

I am far from the first to say that the way education systems are set up across Europe are still beholden to the method of accessing and the availability of information as it was, well, pretty much when public schooling was established by Maria Theresa in 1774. Sure, the classrooms have smartboards and offer computer classes now, but there is only limited space to encourage and give space to independent thought. Most importantly, children are not given tools to weigh new information, confront their own biases and prejudices, and recognize the difference between having an open mind versus accepting whatever comes their way. It’s partly due to the pan-European (maybe I’d go so far as to say international) issue of underfunded education, low educator salary, and high student to teacher ratio. Also, it’s because the methods of educating future teachers to educate are frozen in time. Now, I’m not saying this is absolutely universal, or that we can’t find exceptions. We do see things changing, but the speed of systemic change sorely lacks behind the pace of the shift in information gathering.

The topics and issues I’ve outlined here do not form an exhaustive list, but dealing with their proponents is certainly exhausting enough. If you live outside of Europe, the vast majority will be familiar to you, too – which just shows that pseudoscience, woo, and quackery are without borders, and we as skeptics have to keep working to overcome ours.

Pseudomedicine

The Physical

Also known as CAM, Alternative Medicine is here to stay, no matter how harmful it can be, directly, indirectly, or both. A healer by any other name would smell as fishy. And they do. Metaphorically. I don’t go around smelling them.

Homeopaths, naturopaths, autopaths (that’s the one where you rub your spit on your forehead to get rid of cancer), TCM practitioners, energetic healers… No matter how well-meaning they are, they take advantage of medical workers’ overworked-ness and the limited allotted time physicians spend with patients. They do this by offering an ear without time-constraint – for a hefty price – to give advice or to administer their version of ‘care’, which can hardly be called that.

Science-y Pseudomedicine

Lately, there has been a surge of what I like to call science-y pseudomedicine coming in from the West. This includes the CDS/MMS movement (diluted bleach drinking), Functional Medicine practitioners, magnetotherapy, high-Vitamin C doses, and interest in thermography as an unfailing cancer-diagnosing method, as well as the creation of fake diagnoses such as chronic Lyme disease or Leaky Gut syndrome. Patients with chronic Lyme do present with actual symptoms and often end up being diagnosed with MS or ALS. Still, the fake diagnosis leads to them wasting valuable time during which treatment to slow the onset could have been administered.

Another issue is the mushroom-like popping up of various pseudomedical clinics, which usually have medical doctors, but the care on offer is a far cry from science-based medicine. Though many pseudomedical methods have originated worldwide, they tend to get extra clout and popularity after rising to the USA’s spotlight and then moving eastwards to Europe.

For example, the yoni-egging and vagina-steaming practices truly hit it’s heyday after GOOP made it a thing. Interestingly enough, the proponents of these practices do not connect themselves to GOOP but only promote the story GOOP created – it being that both of these practices are ancient pearls of wisdom done by women for millennia. Similarly, in the last few years, we’ve seen a rise in Europe of teething amber necklaces and bracelets after they went through the USA’s wash cycle.

Credentials

A whole new special area of pseudoscience is weird or fake credentials. Most of Europe is very particular about the use and misuse of academic titles. This is something quite well-regulated. However, I would be amiss to say that there aren’t attempts to pretend to be a Ph.D. or an actually certified specialist. It is interesting to see the influx of imported titles from the US, which here mean nothing entirely, but are trotted out to amaze the public – often successfully. The practice of handing (bogus) title-included certificates is growing its roots, as is the adding of various letter combinations, before unseen, before or after one’s name.

The Mental

If you are not on a self-discovery journey led by a life coach who was not a very successful IT guy a year ago, who even are you?

Self-development is all the rage. You can uncover your true manly-man masculinity or your inner goddess in male and female circles. You can discover the concentrated energy in your pelvic area in a Quantra workshop. It’s a mix of quantum physics and tantra; if you ever get the chance, visit one; for the rest of your life, you will always have a story to tell in awkward silences. You can go retro with some good ol’ Scientology auditing. If you prefer a less beepy and wiry way to create false memories, check out a regressive therapist. To honestly know who you are, all you have to do is take a personality test using the Thomas Erikson method or try Human Design. Its creators have managed to fool some psychologists that this poorly disguised Forer sheet is a thing.

In all seriousness, it was expected that mental health care’s destigmatization will leave the door open for all kinds of alternative mental health therapies. Of course, psychology as a discipline has a layer of its own pseudoscience covering evidence-based treatments, such as a Freudian fascination with Freud and Jung, not to mention the replication crisis and all that jazz. It’s definitely an area we as skeptics have to do a better and more thoughtful job of addressing.

Anthroposophy

A special mention goes to this particular school of thought, since not only do they have their own schools, banks, and medicine, they do their part in trying to shut up their apostates, as is the case with Gregoire Perra, currently being sued for writing a reveal-all blog. He is under the attack of three law-suits. You can find out more and support him on the Waldorf Watch News.

The Miracle that Is Weed

Yes, the tales of the cannabis cure-all have reached our shores, too…

I’ll be back next month to continue my round-up of pan-European pseudoscience, so check back for more from me then!