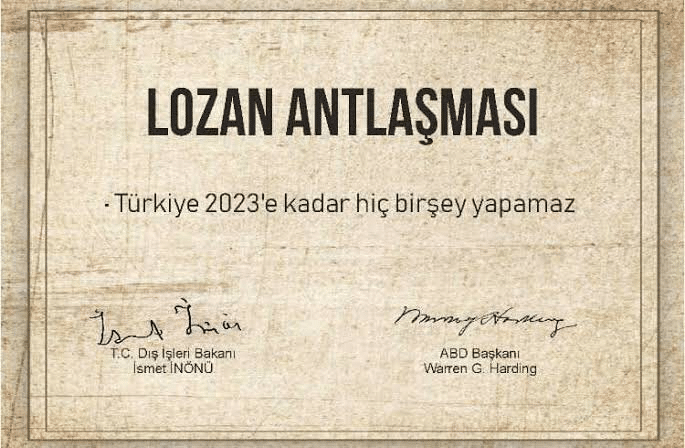

The year 2023 began with a series of jokes in Turkey about people eagerly awaiting the start of the new year to begin digging in their gardens, hoping to uncover valuable resources, including gummy bears and rivers of crude oil. The running theme of these jokes is to poke fun at a conspiracy theory surrounding the Lausanne Peace Treaty, considered the foundational document of modern Turkey.

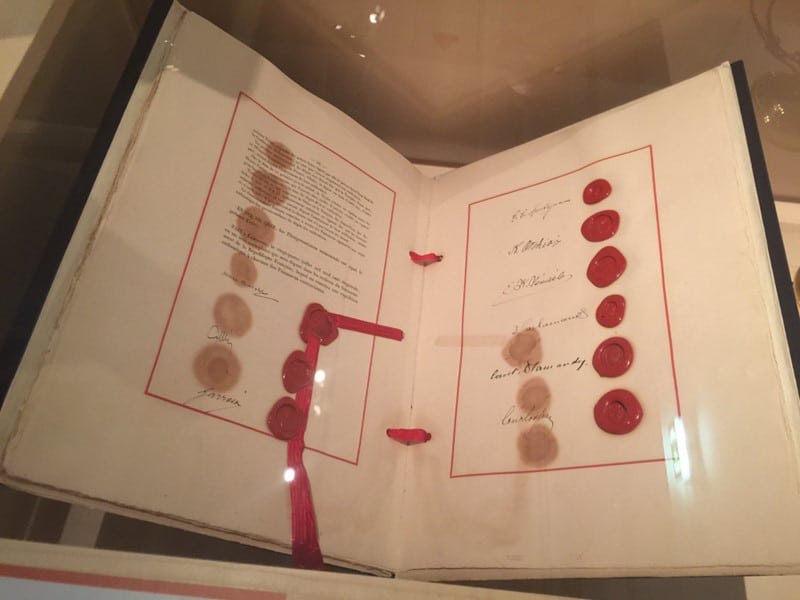

The plot asserts that there is a secret 21-article appendix signed in the cellar of the Lausanne Palace Hotel, and that the treaty will expire on its 100th anniversary. The further claims fall into two categories: First, some believe that with the expiration of the alleged secret appendix to the Treaty of Lausanne, the current government of Turkey will be able to access valuable boron minerals and oil reserves and collect taxes from the straits. The second and less prevalent belief is that the treaty’s expiration will cause Turkey to lose all of its accomplishments overnight.

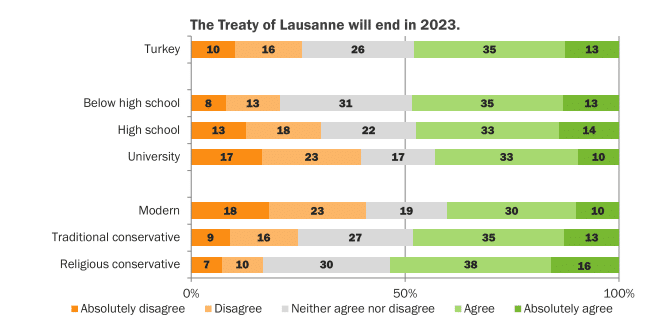

These theories, while nonsensical to critical thinkers, are quite prevalent. A 2018 survey by Konda Research found that 48% of the sample population agreed with the statement, “The Treaty of Lausanne will end in 2023”. The belief in this conspiracy theory doesn’t appear to be limited to any particular ideology. The results are likely due to a broader narrative unfolding over 150 years of modern Turkish history.

Duel of Treaties: From Sèvres to Lausanne

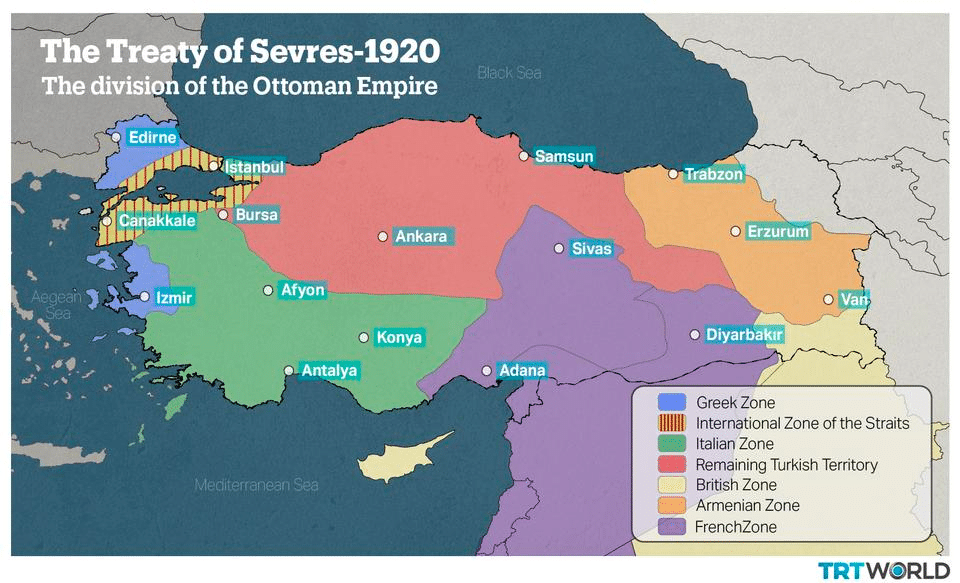

Before delving further into this topic, it is helpful to review the history of the interwar period to understand the context better. In the aftermath of World War I, the Allied Powers and the Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, intended to implement the partitioning of the empire’s territory that had been decided through secret agreements among western nations. Although the Treaty of Sèvres was never ratified, some historians consider it a contributor to the “Sèvres Syndrome“, a historical trauma for the Turkish nation. The negotiated map depicting the slicing of the nation by the “enemy” has been etched into Turkish people’s memories through history lessons taught in primary schools (Tziarras, 2022).

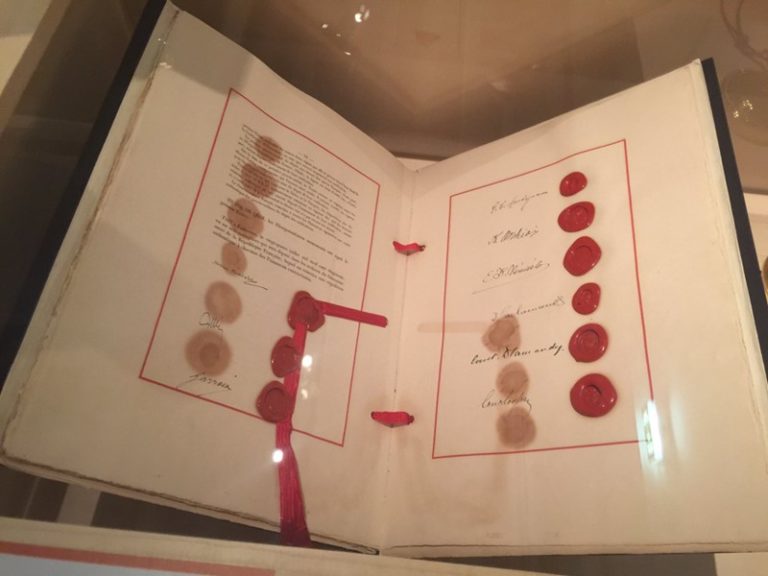

As discussions around the Sèvres continued, a spark of resistance emerged away from the capital. The Turkish National Movement, led by Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), separated from the Ottoman Empire and established a new parliament in Ankara. The movement aimed to establish the National Pact (Misak-ı Milli) as its foundation, which rejected the Treaty of Sèvres and defined the borders of Turkey to the point when the Ottomans were surrounded. They eventually waged a War of Independence against occupying forces, which ended with a Turkish victory in the autumn of 1922. This conflict set the stage for negotiations that ultimately led to the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne in July 1923, which formally recognised Turkey’s sovereignty and set its borders.

The negotiation process was a lengthy and challenging ordeal that required compromises for the founding leaders of Turkey. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president of Turkey, appointed his right-hand man and Chief of General Staff, Ismet Pasha (İnönü), as the head of the Turkish delegation.

One of the major issues was the city of Mosul, which was part of the National Pact; the Turkish delegation tried, and failed, to convince Lord Curzon, the British Foreign Secretary, that Mosul should therefore be part of Turkey. Turkey also did not obtain complete control of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, and had to give up additional territories from the National Pact.

Some of these issues were to be resolved in the 1930s, but the Lausanne delegation faced harsh criticism from Mustafa Kemal’s political opponents, known as the Second Group, during the conference. The arguments were so intense that a prominent member of the Second Group, Ali Şükrü, was assassinated by a former commander of Mustafa Kemal’s special Bodyguard Regiment. The opposition group was eliminated before the treaty was signed.

Pro-Lausanne vs Counter-Lausanne

As a significant symbol in the history of modern Turkey, the Lausanne Treaty represents a moment of victory after two centuries of decline, and an opportunity to start anew after the Ottoman Empire’s darkest times. The Empire had surrendered its resources and independence to its enemies, yet Turkey was the only country to avoid the Allies’ harsh terms, even though they had lost World War I. The treaty marked a turning point towards a new future for independent Turkey.

Before the emergence of conspiracy theories, a contrarian narrative started in right-wing circles based on the “Lausanne as a victory or defeat” discourse. This counter-Lausanne sentiment was represented mainly by ideologies such as Islamism and Neo-Ottomanism, and heavily influenced by the opposition of the Second Group to the withdrawal from the National Pact. However, there were other factors: the nostalgia and aspiration for the Ottoman Empire’s former glory and magnificence, the abolition of the sultanate and caliphate, and the strict (French-style) secularism implemented against the Muslim lifestyle and Islamic traditions have all contributed to the counter-narrative (Tziarras, 2022).

Jewish plot

At this point, those familiar with conspiracy theories may wonder where the Jewish plot comes into play. As Aaron Rabinowitz has often pointed out, there seems to be an “inverse Godwin’s Law” in which conspiracy theories tend to involve an antisemitic angle if they persist long enough.

Enter the Jewish plot into the conspiracy. One member of the Turkish delegation present in Lausanne was Chaim (Haim) Nahum, the Grand Rabbi of the Ottoman Empire. Nahum was known for his close relations with the British and the French. The Ankara government included him in the delegation to leverage his connections, and to signal their intention to reconcile with non-Muslim communities. However, this pragmatic decision has since been subject to conspiratorial interpretations. For example, another member of the delegation, Rıza Nur, wrote in his memoirs about a strange encounter with Chaim Nahum during the negotiations. He implied that Nahum, whom he referred to as a “seasoned Jew”, approached İsmet Pasha with his “typical Jewish pushiness”. Nur claimed that he saved İsmet Pasha from the Rabbi’s influence, but this incident added to the conspiratorial interpretations of Nahum’s presence at Lausanne (Gürpınar, 2020).

The rumours of a Jewish conspiracy gained traction in the counter-Lausanne narrative with the emergence of a series of articles titled “Expose” and “Ismet Pasha and the inside story of Lausanne” in 1949-50, written by an author using the pseudonym “Detective X One” in the Büyük Doğu (Great East) magazine. The true identity of “Detective X One” was Necip Fazıl Kısakürek (NFK), an infamous Islamist ideologue who used a pen name to shield himself from political persecution at the time.

NFK was already deeply entrenched in antisemitic conspiracy theories, having translated “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion”, a notorious antisemitic text. He was also a prominent supporter of replacing the secular nationalist republic with an Islamist one. Therefore, he framed the Nahum story following his ideology. According to his perspective, Nahum convinced Lord Curzon to agree to the Turkish delegation’s demands. In return, the Republic of Turkey would abolish the caliphate and distance itself from Islam.

According to journalist Yıldıray Oğur, İbrahim Arvas, niece of Abdulhakim Arvasi, the 33rd sheikh of the Naqshbandi order and also the teacher of NFK in the Naqshbandi order, may have been another potential source of the conspiracy theory. Arvas was an MP during the Lausanne negotiations. In his memoir, he listed some of these secret decisions made during the negotiations, including abolishing Islam and declaring Christianity in Turkey. NFK knew him very well, but the memoir was written after NFK’s articles. Therefore it is a valid question to ask who put the cart before the horse.

AKP and Erdoğan Rhetoric

While the lesser-known Islamist books and magazines were writing about all these conspiracies and ideas, Islamism began to rise in Turkish politics. The first wave was Erbakan’s Milli Görüş Movement, which joined a right-wing coalition in the 1990s. However, with strong opposition from the establishment, they were removed through a “postmodern coup“, which became a significant milestone for the Islamist movement and fuelled their desire for revenge.

The next phase saw the emergence of Erdoğan’s AKP (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, Justice and Development Party), which appeared more compatible with the secular system. The leaders behind this movement were from the reformist wing of their predecessor party. The AKP did not adopt a Euro-sceptic stance and, from the outset, supported a liberal market economy while rejecting fundamentalism. After the financial crash of 2001, AKP rose to power in the 2002 elections. Over time, AKP’s initially liberal and “mildly Islamist” politics evolved into a personality cult centred around Erdoğan, with an increasingly anti-Western and nationalist discourse coupled with growing authoritarianism.

Modern Islamists in Turkey, including Erdoğan, have long viewed NFK as an ideological icon. Therefore, Islamist Erdoğan might have taken a more contrarian stance against the Treaty of Lausanne. However, the reality is more nuanced. Although his government frequently adopted a counter-narrative against the treaty, he, as a populist leader, also acknowledges its significance as a nationalist element in his discourse. The AKP has never officially used the Lausanne conspiracy. In April 2022, Presidential Communication Center (CİMER) responded to a direct question, “There are no secret articles in the Treaty of Lausanne, and there is no article that prevents us from mining.”

Erdoğan adopted a more practical strategy, applauding the treaty’s historical achievements on its anniversaries but promoting the counter-Lausanne narrative on other occasions. His revisionist tactics serve a dual purpose: for domestic politics, he can seek revenge against the old regime; for international politics, he can leverage the anti-Lausanne narrative to advance his Neo-Ottoman agenda.

In several instances, conspiracy theories were directly promoted by close circles of the AKP. For example, Yeni Şafak, a daily newspaper known for its hard-line support of the Erdoğan government and infamous for its fabricated “milk port” interview with Noam Chomsky in the past, claimed that Erdoğan personally instructed the Foreign Ministry to publish the secret articles of the Treaty of Lausanne. Many AKP supporters linked their hopes for a new and improved Turkey with the treaty’s expiration, in parallel with AKP’s Vision 2023 plan and the “New Turkey” sentiment. Conspiracy-minded secularists were not comfortable with the idea of the Treaty’s expiration and worried about Erdoğan’s possible secret intentions to replace Ataturk’s legacy.

With social media, the conspiracy theory was transformed from its original form. Rather than focusing on the “Lausanne as a victory or defeat” narrative, the theory began incorporating urban legends, such as foreign powers preventing Turkey from extracting boron or oil reserves. These urban legends may have diluted conspiracy theories that once accused the founding leaders. One speculation could be that the rise of ultra-nationalism on the left and within Islamist circles may have contributed to this change.

Conclusion

We aimed to trace the origins of the conspiracy theories surrounding the Treaty of Lausanne and uncover the political agenda behind them. These theories exemplify a tendency to interpret historical events imperfectly and with motivated reasoning rather than critically assessing historical sources. For some, an alternative explanation was necessary to sustain the anti-Lausanne narrative. For others, it was to conform to their ideological stance or predisposition towards victimhood. Eventually, everyone fabricated their own stories and provided a plausible rationale suited for themselves. As Rob Brotherton pointed out, “Conspiracism is just one potential product of a much broader worldview” (Brotherton, 2015).

While these narratives may seem amusing or irrational, they can have real-world implications and shape public opinion. Understanding the origins and evolution of these conspiracy theories is crucial to uncover the underlying social and political forces driving their popularity. This knowledge can offer insights to combat the spread of misinformation and promote a more informed and nuanced discourse.

Further reading

- Zenonas Tziarras (2022), Turkish Foreign Policy, SpringerBriefs in International Relations – 2022

- Gürpınar, Doğan (2020). Conspiracy Theories in Turkey, Taylor and Francis

- Brotherton, Rob (2015). Suspicious minds: why we believe conspiracy theories. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Sigma