Since 2009 I’ve been producing the skeptical podcast ‘MonsterTalk‘ and over the years we’ve always – from the very start – expressed deep skepticism about the existence of various cryptids. But the way people consume podcasts is often incredibly spotty and eclectic these days. If someone hopped into the show and wanted to find out about why we’ve come down so hard as skeptics about these critters, it might not be that simple right now to piece together all the various converging ideas that have led me to this position of doubt. I think it would be useful to put together some essays about why – despite so many compelling sightings and slick documentaries and videos – I don’t believe in various monsters.

And if I’m going to kick off a series about doubting cryptids, I have to start with the one that got me into cryptozoology: Bigfoot.

Bigfoot’s popularity – at least in the US – is hard to overstate. The Bigfoot Field Research Organization (BFRO), which organises bigfoot hunts and was a big part of the TV series ‘Finding Bigfoot’, boasts more than 5,000 uploaded reports of bigfoot sightings in their online database. And that television show ran for nine seasons without – you know – finding Bigfoot. I’ve been to bigfoot conferences and met very sincere witnesses who believe they encountered a giant anthropoid ape in the forests of America. I don’t think they’re lying – but how could they all be wrong?

I think it may help if I describe the framework I use to evaluate the existence of Bigfoot and other monsters. We often call it ‘scientific skepticism’ but we don’t often break that down to describe how it works. Over the years I’ve come to believe that this approach is basically an algorithmic approach to testing the claims, and – critically – is a set of skills that have to be learned and honed, not a sign of special cleverness on the part of the person wielding it.

Plausibility

I usually start with asking how plausible the existence of the described creature is from a purely biological framework. Does it fit the pattern of known biology? For example, some monsters like a European Dragon break the tetrapod body framework if they have four limbs plus giant wings. Similarly the Jersey Devil and most modern depictions of Mothman – there aren’t any human-sized hexapods walking the earth, nor recent antecedents. Such creatures break from plausibility in their sheer unnaturalness from known body types.

History

Then I ask whether this is a new kind of creature, or one with a long history. Cryptozoologists love to talk about how Europeans didn’t believe in gorillas but this is not the same situation as, for example, the Yeti. Mountain Gorillas were once treated like a myth or a legend by European scientists and thus, like the coelacanth, have become venerated within cryptozoology as legendary monsters of folklore that turned out to be real. There are real problems with using either of those animals to justify cryptozoology. Gorillas were real animals, not just folklore. The scoffing of European scientists about Gorillas ended when type specimens proved they existed. And the coelacanth was not found by investigators trying to test folklore – it was a serendipitous discovery of a rarely seen fish. Once people knew where to look for these real animals, their material reality was confirmed. We’re still waiting on Bigfoot.

Signs of Folklore

There are a variety of features that indicate a story is coming from emerging or extant folklore and I like to see if the stories fit into that framework. Are people explicitly named in the story or are they either nameless strangers; ‘a girl’, ‘a businessman’ – or even more tellingly, friends of a friend: “My cousin’s friend upstate told her this so I know it’s true.”

Does the story follow tropes common to folklore like those in the Stith-Thompson Folklore Index or like those listed on TV Tropes? These recurring patterns are good indicators you may be dealing with a bit of nascent folklore.

Hoaxes or Shenanigans

Sometimes the whiff of a hoax is pretty obvious, and it’s good to at least consider that possibility, even if the initial claimants seem very sincere. The person reporting a hoaxed event may not even be aware they’ve been tricked. Does anything about the story suggest it might have been staged?

These are very high-level considerations but they’re good starting points to get a sort of “whiff value” of whether the monster or cryptid is implausible. Let’s apply these categories of critique to Bigfoot and see how the big guy comes out.

Plausibility of Bigfoot

Is there anything overtly implausible about Bigfoot? This is a trickier question than it might seem at first glance. We know humanoid primates exist, because we are them. Could a giant hidden primate exist? There’s nothing inherently impossible about that. But could a giant hidden primate exist and be seen by thousands of people and yet never leave ANY physical remains that could be positively identified as having a DNA profile consistent with a new, unknown primate? Suddenly the plausibility begins to teeter.

The missing physicality of Bigfoot is much more consistent with it being a socio-cultural concept than a real animal. And if one were inclined to believe in Bigfoot but have to explain this drought of positive biological data, out comes the special pleading. The legendarily acidic soil of the pacific northwest somehow manages to give up bones of all the other large animals in the ecosystem – but Bigfoot just can’t produce.

The late Grover Krantz used to claim nobody had ever found the remains of a naturally dead bear – but that argument has a couple of problems as analogy. First, people find plenty of living bears as well as kill them routinely, so it’s not a perfect analogy. Second, he’s just wrong. People DO find naturally dead bears – and I’m not even sure what he meant other than to try to carve out some argument space for his pet monster’s plausibility.

Perhaps more importantly, Bigfoot does not really behave like a natural animal, if you listen to a broad swath of reporting and don’t exclude that including quasi or explicitly supernatural elements. Bigfoot – for many – behaves like a spirit or extraterrestrial or alien intelligence. Seriah Azkath of ‘Where Did the Road Go?’ (and his guests) has referred to them as “forest poltergeists” and I think he’s dead accurate – right down to their alleged propensity to make knocking noises and throw stones.

Collectively, this all stacks up as implausible to me, at least so long as we’re limiting explanations of this cluster of phenomena to natural explanations.

History of Bigfoot

Ignore the cryptozoology claim that Bigfoot is an ancient creature. That’s a favorite assertion for lots of monsters, because anchoring a monster’s existence to ancient times makes it seem like it has always been part of the landscape and modern sightings are just the peak of a wave that stretches back beyond the veil of recorded history.

Instead, let’s begin with ‘sasquatch’ – a term commonly interchangeable with ‘bigfoot’ these days, but both terms are from the 20th century. Before the 1950s there was no such thing as ‘Bigfoot’ as we know it. A variety of indigenous stories of tribes of hidden giants and monsters were syncretised by “Indian Agent” J.W. Burns into the concept of ‘Sasquatch’ in Maclean’s Magazine on 1 April 1929.

In 1957, the Canadian resort town of Harrison Hot Springs tried to win $600 in funding from a British Columbia centennial committee by proposing a ‘sasquatch hunt’. They didn’t get the funding, but the request became a global news story and made the word ‘sasquatch’ synonymous with the wilds of the Pacific Northwest. The committee didn’t give Harrison Hot Springs the $600, but they did put up a $5000 prize for anyone who could bring in a live sasquatch. All of this coverage also led to at least one notable witness coming out to tell a strange story.

William Roe came forward with a story quite different from the ‘giant hidden tribe’ tales common to many indigenous stories. What he saw was not a person with mysterious language and custom, or backwards facing feet. Rather, he described seeing a hairy, gigantic, female upright ape. His sighting, he claimed, took place earlier in 1955. The Roe affidavit could be argued to be the real ‘case zero’ of Sasquatch in the way it has come to be seen by modern audiences. Other historical cases would be retro-fit to match his prototype – but that’s not the full story.

Recall that the world had been primed for giant primates by the explosive photos of mysterious footprints in the Himalayas by the Shipton Everest expedition of 1951. Although the yeti (or abominable snowman) had not been photographed, the idea that there might be a mysterious living upright ape was definitely in the public consciousness by the time of the 1957 Harrison Hot Springs story and William Roe’s account.

Roe’s story grabbed a foothold down the Pacific coast in California. In 1958, a series of enormous footprints and some minor vandalism at Jerry Crew’s logging site in Bluff Creek, CA became the most important hoax to date. Giant tracks appeared several times around the construction equipment, and Crew’s employee Ray Wallace cast some of these in plaster and later presented those tracks to the newspapers. The papers referred to the creator of those tracks as ‘Bigfoot’, although the real creator was Ray Wallace himself, who turned out to be a lifelong practical joker.

Texas oilman and adventurer Tom Slick had been fascinated by the Yeti and had funded expeditions to try and find it – but these were expensive and fruitless, so when the stories of an “American Yeti” hit the papers, Slick moved his monster searching to the United States. His first big American expedition kicked off in the fall of 1959. He would continue to fund monster hunts until his death in a private airplane crash in 1962. Slick’s search team would include people who carried the Bigfoot flag for the rest of the 20th century.

Into this rich broth of monster stew we now add the colorful character Roger Patterson. A cowboy and rodeo performer, Patterson seemed to be the kind of person who was always scheming for the next get-rich gimmick. Through many different accounts, he comes across as the sort of person who is extremely entertaining to know, but one whom you would quickly realise isn’t going to pay back that loan or return that stuff he ‘borrowed’.

Patterson was captivated by William Roe’s account of spotting a sasquatch and in 1966 he published a book titled ‘Do Abominable Snowmen of America Really Exist?’ In the book he includes an illustration of the creature Roe described, a thick and hairy female upright ape with pendulous breasts walking into a clearing. In 1967, Patterson and his friend Bob Gimlin took film equipment into the Bluff Creek area.

If you believe the story the pair told (and which Gimlin maintains to this day), they were going into the woods to look for bigfoot and on their first outing they came across one of the creatures and filmed it walking near a creek bed. That they would succeed on their first try, where others had spent years looking with no luck, is quite a coincidence.

Stabilised and upscaled, the Patterson-Gimlin Film (PGF) has become a Rorschach test for belief. If you see a creature compatible with the person-in-a-suit hypothesis, this will confirm your suspicion. If you favour the unknown-animal hypothesis, then you’ll likely wonder why anyone can see this footage and not be captivated by the mystery.

The other way to look at it is to consider that Patterson had been trying to put together a pseudo-documentary about the hunt for the creature and might have been shooting a sort of ‘sizzle reel’ – a short sequence of film to drum up interest and funding. In this view, the creature would have been a man in a suit and the drawing Paterson made of the Roe sighting would be less of a speculation and more of a storyboard.

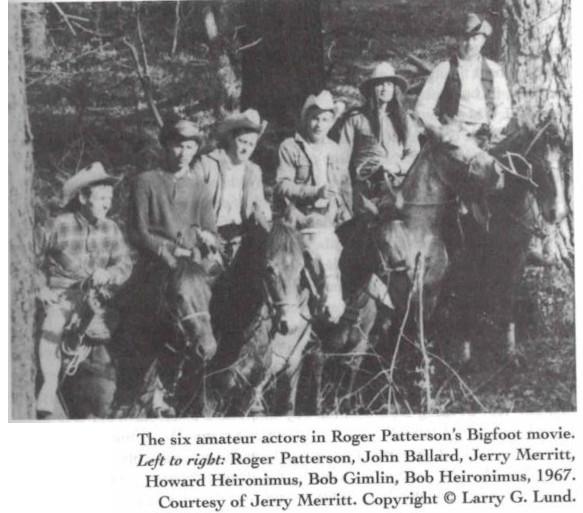

Greg Long’s book ‘The Making of Bigfoot’ features this rare shot of Patterson’s pals working on his movie project. Bob Gimlin is dressed as an ‘Indian tracker’ with a long, black wig. This concept was re-used in the film ‘Sasquatch: The Legend of Bigfoot’, which itself utilised Patterson’s Bluff Creek shaky-cam footage as documentary evidence in an admittedly fictionalised framing. Colourised versions of this shot occasionally pop up on the internet.

But this is not a skeptical take-down of the PGF. People who want to believe Patterson got lucky and happened to catch the elusive creature on film his first time out – and that decades of further research can’t replicate the results – are not going to be dissuaded by anything I could write here.

Still, the PGF became the template footage for all Bigfoot sightings to come, and its notable success being toured around the Pacific Northwest surely inspired the string of indie films that would attempt to cash in on this monster craze: ‘The Legend of Boggy Creek’, ‘Creature From Black Lake’, ‘Night of the Demon’, ‘Sasquatch: The Legend of Bigfoot’, and eventually the comedy parody of such films that was also the pinnacle of presentation, ‘Harry and the Hendersons’.

Nowadays Bigfoot has become a pop culture icon, and I would argue that this is the whole of what he ever was. Excluding the idea that the collective belief of millions might have generated a Tulpa as a psychic reification of the creature – an idea seriously believed by many – the best explanation that fits the history is that, from the 1920s to the 1970s, the lore of Bigfoot evolved until it was naturally selected down to the core elements that best propagate in late-20th and early-21st century America. And, as I mentioned under plausibility, the selective pressure is leaving the ‘pelts and paws’ version of the creature behind. Bigfoot leaves only footprints and takes only liberties when it comes to our collective narrative permissiveness.

Folklore of Bigfoot

Is Bigfoot folklore? I would argue that the history suggests Bigfoot descended narratively from the 1950s conception of The Yeti as rewritten through Colonial exploration of the Himalayas. The Yeti – which should have its own dedicated examination – comes from a rich folkloric tradition that features supernatural elements and things like its feet facing backwards to confound trackers.

These are features that have been included in catalogs of folklore motifs. If I’m right about my historical context for the rise of Bigfoot, then the creature is much better understood as a specialised form of folklore than as a real biological animal. Its ecological niche may be less lovers’ lane or strange hotel rooms and more the minds of 20th and early 21st century dreamers, longing for a more mysterious world and a nature big enough to house other intelligences than humans’.

Most of the bigfoot stories I’ve read have been deeply personal accounts that seem sincerely shared. I don’t think the folkloric nature of bigfoot and the lived experience of having encountered one need to be mutually exclusive. Sincere witnesses can misperceive the kinds of things one experiences in a forest, and many natural half-glimpsed movements and unexplained noises readily fit the cultural template of a bigfoot encounter. It doesn’t require fabrication on the part of the witnesses.

But sometimes things aren’t so clearly sincere.

Hoaxes and Shenanigans with Bigfoot

Does the existence of Bigfoot depend on hoaxes? This one is astonishingly clear cut, to my mind. The Ray Wallace hoaxed footprints literally gave us the name Bigfoot, and the visuals we connect to the imagined creature that could have made those tracks is brought to us by what I believe to be the obvious hoaxed subject of Roger Patterson’s film. Numerous hoaxers have perpetrated a form of recursive ostension to feed the Bigfooters with handcrafted plaster casts, and costumes of varying quality, and pale imitations of the PGF.

This does not mean that Bigfoot witnesses are liars or hoaxers – but the sincere witnesses are not clean slates. They’re operating in a cultural ecosystem rich with the readily available template of Bigfoot to explain their peculiar sightings or experiences in the wild. Bigfoot’s ‘natural world’ is a trickster’s paradise.

Conclusion

Clearly there are many more nuanced arguments for and against the existence of Bigfoot. Individual sightings should be considered with their own evidence under forensic and logical scrutiny. In the end, Skeptics can no more relegate Bigfoot to the Platonic bucket labeled ‘not real’ than they can ghosts or UFOs – but the preponderance of the evidence against the creature existing as a natural animal is overwhelming to me.

Bigfoot isn’t my Moriarty. I love the big galoot and somehow, after a lifetime of wanting it to be a real animal, I’ve come to peace with the idea that this simply can’t happen because that’s not what Bigfoot is. Of course it would only take a single corpse or DNA sample to prove the skeptics wrong – if the lab results bear up.

Further Reading

- Abominable Science by Daniel Loxton and Don Prothero

- The Making of Bigfoot by Greg Long

- Anatomy of a Beast by Michael McLeod