Come election time, there tends to be bragging rights or shame attached to GDP. GDP seems to be our foremost measure of success or failure. Some nations might also highlight increased military force, industrial dominance, possibly even international influence. But GDP is invariably the big focus.

But what if, like some geopolitical version of the Eurovision Song Contest, we demonstrated our superiority over others by being the cheeriest, healthiest, freest, sportiest, most trusting nation on Earth? What if happiness was the measure of a nation’s success?

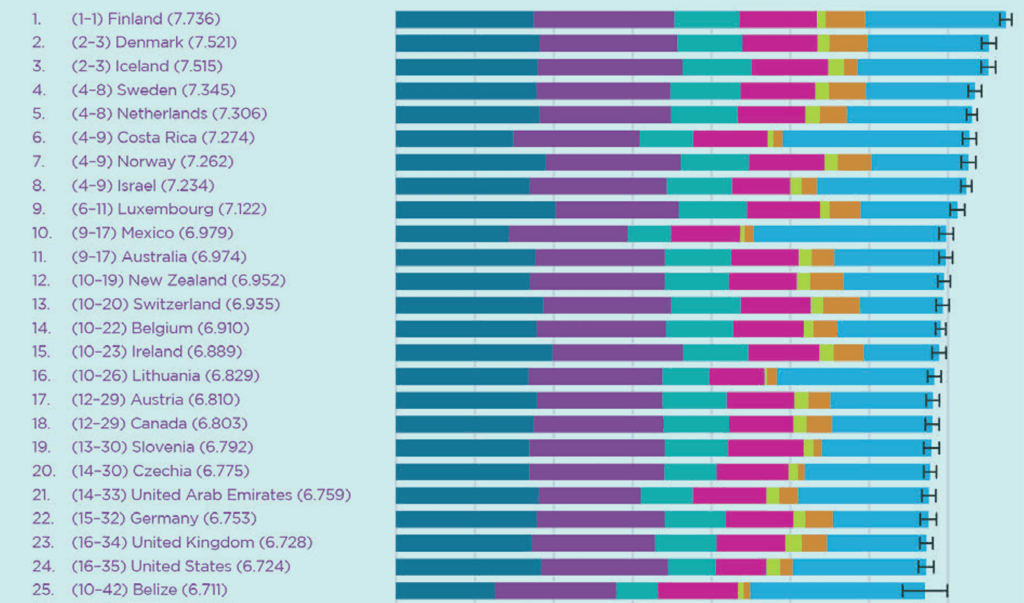

World happiness has been measured, using some pretty sound methods, for the last 14 years, since the idea was first proposed by Bhutan in 2012. Every year, the UN publishes its World Happiness Report, in which it ranks 147 countries (the number of countries for which it has access and accurate data) by overall happiness. So far, Finland is the overall winner. Other Scandinavian countries hog the top five slots.

When Donald Trump spoke at the UN General Assembly in September 2025, he claimed Europe was “going to hell”. He criticised what he called the failed experiment of open borders. He told the world the UK had a London Mayor enforcing Sharia Law. His bleak and sweeping appraisal of an entire continent is not just wrong, it ignores how poorly his own country has been doing of late.

An interesting trend that Trump might observe, were he to look, is the consistent downward movement of the USA. In 2012 the USA was ranked 11th (an excellent ranking in the scheme of things), but has since then fallen to a record low of 24th in 2025.

Another interesting thing Trump would be able to observe in the data is this: 15 of those top 20 ranked countries are European. Is Europe really going to hell? Or is Europe doing amazingly well?

Meanwhile, here in the UK, over the period 2019 to 2025, we have dropped from 13th to 23rd. Shouldn’t that be worthy of our attention? Dropping out of the top 20 ought to be alarming. Dropping just one place should be newsworthy. Questions should be asked in parliament. But media outlets – if they focus on this at all – tend only to point out that the winner is Finland. Again. And the winner always being Finland makes it a second-rate story.

You might be wondering how happiness is measured. Do UN officials go round the globe asking people if they are happy? Well, yes. Asking people that one simple question is a big part of the research.

Each year they sample-survey well over 100,000 people in more than 140 countries. The exact number varies, but a sample of around 1,000 people is common for each country. Reports always combine the last three years of data to produce current rankings.

But the final ranking is also based on hard data and the sum of several carefully observed parts of a national picture. The six key things they look at are GDP per capita (sorry, can’t be avoided), social support, healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices, generosity, and the perception of corruption.

Costa Rica, which has no standing army to fund, sits in the top 20. It can more readily spend its small but significant capital on practical social policies. It’s a brave road to go down. Happy and defenceless. Unlike Finland, which is happy, fully armed and ready for anything.

Finland has compulsory military service, and the young people who turn up to train know why that’s important. They share a land border with Russia. Patriotism is a mix of cultural pride and a very real solidarity against a rather nasty, very real existential threat.

Like other Scandinavian countries, they tend to have coalition governments implementing progressive but well-researched social policies. These ensure it’s almost impossible to drop out of the bottom of society. Taxes are high, but people trust that the money is being spent wisely.

Also, Finland claims ownership of Santa Claus. The population is trained in Tundra warfare. They have fully stocked nuclear bunkers, and not just for the leader-class, but for every Finnish citizen.

Social policies like those we see in Finland are not just feel-good people-pleasers, they are backed up by sound economics and science. By way of an example, Denmark (ranked second), offer fathers 480 days of paternity leave. Denmark knows that women are statistically more likely to have attained higher levels of education than men. Therefore, they are statistically more productive and in more senior positions in the workplace.

On a purely practical level it makes sense for Dad to look after the baby. Other emotional and wellbeing benefits follow. Similar policies, deceptively impractical and idealistic to the casual observer, are common across this part of Europe.

A second illustrative example of this type of thinking is the Danish wind turbine policy. In the same speech to the UN, where Donald Trump claimed European countries were going to hell, due to immigration, he also denounced Europe’s energy plans and the climate change ‘hoax’.

We won’t deal with his argument here. But we can consider how Denmark has dealt with the potential friction caused by building huge wind turbines near populated areas. Taking a very different approach to that seen here in the UK, the Danes told residents exactly which individual wind turbine belonged to them, awarding them a sort of ownership. They explained this particular turbine is currently powering your street – very cheaply. It was a simple, clever idea that all but extinguished resistance to wind turbines.

Another interesting part of the UN research package is the ‘dropped wallet experiment’. Wallets are dropped in various places to see if they’ll be returned. Each wallet contains the equivalent of $200. The test is used to show that people are, on the whole, pessimistic about the kindness of strangers. But also, that the rate at which the lost wallets are returned is about double what people expect.

This belief, or lack of belief, in the kindness of others is a strong predictor of wellbeing. Benevolence, or the act of making the effort to find the wallet-less person, is a good measure of happiness, and also a good source of happiness.

In these tests, Finland consistently has the highest rates of returned wallets. Canada also scores well.

The true end goal of societal organization is to make life as good as possible for everyone, collectively. GDP is one way to achieve this by pooling resources, but other means exist. Well-being is a crucial indicator of a good life.

Micael Dahlen, Swedish author, public speaker and professor of wellbeing, welfare, and happiness at the Stockholm School of Economics

So while the USA drops to its lowest ever position in the Happiness Index, those Scandinavian countries stay solidly in the top 10. The UK and the USA, with their innate senses of ‘global superiority’, might be expected to be more vocal about not being in, or even near, the top 10.

More recently the UN has included one extra side study to each annual report. Last year this focused on the happiness of children; in 2025 they looked at how eating together affects happiness. The findings from the USA were quite revealing. Roughly one in four American adults report eating all of their daily meals alone, an overall increase of more than 50% since 2003, the report stated. Sharing meals is a powerful indicator of well-being, broadly equivalent to factors like income and employment status.

It would be foolish to see Finland and Denmark as the owners of absolute happiness. They have in no way achieved that. They’re just doing a tad better than the rest of us. If we see them – for argument’s sake – as currently achieving 25% total possible happiness, that could help the rest of us see just how much is left to do. Or see just how poorly the majority of countries are sustaining a happy population.

The issues Donald Trump identifies in his ‘gone-to-hell’ analysis of Europe centre mostly on immigration. He’s seemingly offended that Europe isn’t 100% white and Christian. Scandinavian countries are also currently dealing with a range of issues associated with the recent rise in immigration seen across Europe.

Sweden has been bulking up its police. Denmark is forcibly moving some immigrant families out of their homes and rehousing them in another area in an attempt to avoid a ghettoising effect and to promote integration. On the surface this looks sinister. But it is certainly not an America First-type policy of round ‘em up / kick ‘em out. Time will tell if it has a broadly positive effect.

Policies like these are not worked out in secret or enacted covertly. Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland all have ‘open government’, meaning policy decision making is visible to all. Whatever future policies are implemented, they will likely to be based on proper research, social science and a sense of fairness.

The Skandi approach is to try something logical. And given they keep very few secrets from the world – an uncommon level of trust in Government is really the hallmark of this whole region – their approach can be easily read, dissected and copied.

That much of the world doesn’t copy ideas that evidently work is the real mystery.