This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 6, Issue 1, from 1992.

In my article ‘The New Age and the Crisis of Belief’ (The Skeptic 5.2), I explored the probable reasons for the growth of New Age beliefs and practices. Firstly, I argued that human beings have an innate need to conceptualise the world in terms of facts, theories and values to form relatively comprehensive and coherent structures of beliefs – so-called ‘belief systems’. Belief systems may be true or false. They may be supported with evidence and argument, or they may be unsupported. They may be accepted in an open-minded spirit or adhered to in a dogmatic fashion. They may be explicitly formulated or implicitly assumed. And they may be either religious or secular in character. But whatever is the case, they must be ‘workable’ in the sense of providing believers with a satisfying explanation of the world and with a useful guide to action.

Secondly, I argued that we in the West are today faced with a situation of ‘ideological crisis’. The influence of orthodox religious beliefs and institutions has declined in comparison with the past, yet the secular forms of belief (such as Marxism) which helped to displace them have largely failed to take over the central role formerly occupied by the Christian religion. Nowadays, only the values and attitudes associated with pluralist democracy, consumerism and market economics perhaps have a claim to ideological supremacy.

Given the relative weakness of both orthodox, mainstream Christianity and its secular alternatives, and given the persistent need for belief, it is not too surprising that the ideological vacuum thus created should have become filled with many strange new creeds. Thus, whilst it would be naive to suppose that the particular character of contemporary forms of belief is the result of any single cause, the growth of New Age thought, the rise of new religious movements (‘cults’) and even the resurgence of Protestant fundamentalism (and, with it, creationism) must surely be seen as in large part reflecting this present-day ‘crisis of belief’.

This analysis is intended to apply only to the case of Western industrialised societies such as exist in Britain and the United States and it is not necessarily immediately applicable elsewhere. It was therefore of great interest to me when recently I read a couple of articles in the June and August 1991 issues of the popular science magazine Scientific American which shed significant light on the rather different situation existing inside the Soviet Union: ‘Science? Nyet – Disillusioned Soviets Embrace Mysticism and the Paranormal’ by Philip Ross, and ‘Antiscience Trends in the USSR’ by Segei Kapitza.

In contrast to the West, the Soviet Union provides an example of a society which (for a time) successfully instituted a thoroughly secular ideology: that which came to be referred to as ‘Marxism-Leninism’. Yet, it seems an interest in the paranormal, in fringe science and in new religious movements is discernible there also, just as is the case in the West. How are we to understand such beliefs in their proper social and historical context?

Paranormal claims emanating from the Soviet Union are of course by no means a new thing. For example, many readers of The Skeptic will recall the case of the Russian ‘psychic’ Nina Kulagina who achieved a degree of notoriety some years ago by claiming to be able to move objects by the power of thought alone. But according to Sergei Kapitza, a physicist and member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, the profound changes taking place in the USSR associated with perestroika have resulted in a marked increase of interest in the paranormal and in the ‘irrational’ generally.

The evidence is unsystematic and largely anecdotal, and so perhaps needs to be treated with some caution, but Kapitza quotes several examples to support his claim. For instance, he discusses the case of Anatolii Kashpirovskii, a faith healer who has demonstrated his purported abilities on television on many occasions and who has now acquired a large following. The medical profession has apparently offered only feeble opposition to such practices, whilst the Communist party newspaper Pravda actively came out in support of Kashpirovskii’s claims.

Meanwhile, the same newspaper has also provided a sympathetic report on a certain seer from India who (Kapitza tells us) offers advice on political and personal matters. The Soviet news agency Tass (which, incidentally, reported the arrival of three-eyed extraterrestrials in southern Russia some months ago-see Hits & Misses, The Skeptic 4.1) has produced photographs to support the claim that a ten year old girl from Georgia can attract metal objects to herself by paranormal means.

The popular and progressive newspaper Young Communists of Moscow has apparently provided a regular daily horoscope for its readers, whilst the publishing house of the Academy of Sciences has recently released a large number of copies of a book on astrology. Even what purports to be a scholarly journal, Social Sciences and Modernity (also published by the Academy of Sciences), bears a message on the back cover of one of its issues promising the future publication of dialogues with the Cosmic Mind as received by staff members of the ‘All Union scientific coordinating study centre for UFOlogy’!

Such cases can no doubt be explained (at least in part) by the relaxation of censorship that has followed as a result of glasnost and by the fact that publications now have to compete for circulation (and even advertising). The temptation for editors to resort to sensationalism must be strong. But a market for such material clearly exists, and the absence of open dissension and debate that has previously characterised Soviet political culture can only assist the uncritical acceptance and further propagation of such sensationalist stories.

Meanwhile, at a more serious level, a centre for alternative medicine has recently opened in a Moscow hospital and is able to administer unconventional treatments with the full protection of the law; Krishnaites have begun to appear on the streets of Moscow; and religiously-inspired creationism is being imported from the United States. Kapitza is clearly worried by such developments and he is not alone. Loren Graham, an historian of Soviet science at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was recently involved in organizing a joint US-USSR panel to discuss the problem of ‘anti-science’ trends, focusing especially on the case of the Soviet Union, with contributions made by scientists and scholars from both nations. ‘A diminishing in the prestige of science, accompanied by a rise in the prestige of occultism, would not bode well for a free society’, Graham is reported as saying.

What might be the root cause (or causes) behind the growth of such ‘alternative’ forms of belief? One obvious candidate explanation is that such growth can in large part be attributed to the effects of popular disenchantment with the state ideology of Marxism-Leninism. This disenchantment was demonstrated most dramatically during the aftermath of the failed coup attempt of August 1991, which saw statues of Lenin and his confederates come tumbling to the ground, and marked the effective end of over seventy years rule by the Soviet Communist Party.

But of course such disenchantment had long preceded these events and the policy of glasnost had already allowed it a voice. The rise of alternative beliefs such as those described above can probably be seen as one manifestation of that disenchantment Marxism-Leninism, as an ideology and as a political system, failed to satisfy both the material and the spiritual needs of the population, and was extremely oppressive into the bargain. This failure created an ideological vacuum that was perhaps even more sharply felt than the West’s. If the need for belief is as persistent as I claim it to be, then it is not surprising we should find that many people are turning to alternative systems of belief now that they have the freedom to do so.

Skeptics face an uphill struggle in attempting to counter these newly emerging belief systems where these can be shown to conflict with the available scientific evidence. Respect for science amongst even educated Soviet citizens is at present apparently extremely low. The scientism of Marxism-Leninism – the fact that it advertised itself as ‘scientific socialism’ – has clearly not helped improve the status of science amongst the general public. Moreover, its uncritical acceptance of the unqualified benefits of scientific and technological progress helped create the conditions which made possible such ecological disasters as the draining of the Aral sea and the Chernobyl nuclear accident, and has thereby also contributed to a widespread disillusionment with science and all its works.

Nevertheless, I understand that Paul Kurtz is planning to establish a Russian version of the Skeptical Inquirer. One can only wish him well, but there are grounds for doubting how much impact this is likely to have on a nation that seems to be in the process of disintegrating and which faces the prospect of economic and social upheaval on a massive scale. The growth of alternative belief systems seems to me to be likely to continue apace, not least because these belief systems offer security and hope during a time of great uncertainty and crisis.

The revival of more orthodox forms of religious belief also seems probable, and the growth of extreme forms of political ideology grounded in nationalism is a distinct possibility. If the Soviet Union is successful in making the transition to a market economy then the materialism of the consumer society may well offer yet another kind of ideological option. But the Western experience suggests that, even then, a significant minority of the population will continue to seek solace in the occult, in the paranormal, and in other forms of alternative belief, however ludicrous these may often appear to be.

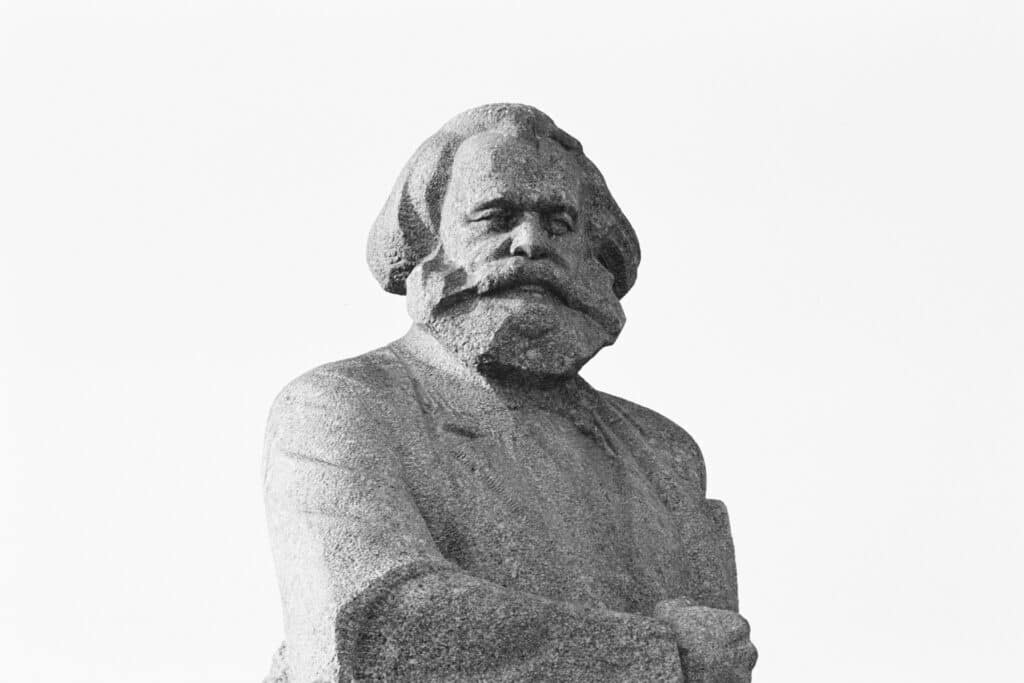

To the extent that such alternative beliefs form part of larger belief systems which are able to confer significance and meaning on the human condition, they can legitimately be described as ‘quasi-religious’ in character, and the persistence of such beliefs is really not difficult to understand. As Marx himself proposed, ‘Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people’.

Of course, Marx’s argument also amounted to a call for the abolition of such illusions through the creation of a society which would not need illusions. But if Soviet-style communism was intended to provide for the realisation of such a society then in time it also was revealed to be a kind of illusion, and it is not yet clear that there are available any truly adequate ideologies to replace it In this sense, the Soviet Union now faces its own more acute version of the Western ‘crisis of belief’ .

Neither crisis is likely to be easily resolved, and it remains to be seen whether or not there are valuable fragments buried deep in the ideological debris of human civilisation which might still form the basis for new perspectives and for new world-views as yet unimagined.