Last month, I wrote about the Better Way antivaxxer conference, including a list of what I felt were genuine problems that speakers raised alongside their antivaxxer conspiracism. These included:

- U.S. pharmaceutical companies can legally advertise directly to consumers across all mediums, contributing to problems like the opioid epidemic.

- Survivors of abuse often have little recourse because corporations are heavily insulated against liability.

- Indigenous communities and their practices continue to be violently suppressed by exploitative colonial governments.

- There are well documented conspiracies involving governments and pharmaceutical companies that have substantially harmed marginalised communities.

- Medicine is rationed either monetarily or through bureaucracy, both of which can feel dehumanising and lead to inadequate care.

- The personal experiences of marginalised individuals are often dismissed by medical experts as unreliable.

- Academic disciplines can be too siloed to address real world problems.

- Our education system is soul crushing and leads to burnout.

This list highlights the challenges with reducing conspiracism in the modern world. It helps us understand and address the root causes of conspiracism, rather than having to treat the symptoms through costly stopgaps like content moderation and counterterrorism.

It also provides a perfect opportunity to discuss some recent philosophical work that pushes back on traditional accounts of conspiracism and widespread loose talk about the psychology of individuals who believe conspiracy theories.

The Particularist and the Generalist

As a philosopher with a lifelong interest in conspiracy theories, I was surprised to find out that philosophers are even doing this work. I’d never come across reference to it in my own conspiracism research, and I’d concluded it was just the sort of applied philosophy topic that is sometimes treated as beneath academic philosophers. Thankfully, M. R. X. Dentith recently reached out and shared some of the valuable work that they and others have published regarding the conflict between particularists and generalists about conspiracy theories.

“Particularism” and “generalism” are philosophical terms of art used across domains to distinguish between two broad approaches to addressing any given topic. Generally speaking, generalists approach a topic by constructing general categories and principles about the specific entities involved in the topic, while particularists are skeptical of such approaches and tend to argue for more case-by-case assessments. For example, generalists in ethics will develop and argue for principles like “it’s wrong to cause unnecessary suffering” as a way to distinguish between good and bad actions. Particularists will then argue that such principles are unsustainable in complex real-world circumstances, and that’s why we have to assess each action in context before we can pass judgment.

Dentith and other particularists about conspiracy theories have argued that a naive and inconsistent sort of generalism dominates this topic, resulting in people using the term “conspiracy theory” more as a vague pejorative than a meaningful description. Dentith argues that there are only three essential properties of a conspiracy theory: conspirators, secrecy, and a goal. A conspiracy theory must claim that at least two people collaborated in secret to achieve a goal. The recent open conspiring by Trump and others to overthrow the 2020 presidential election raises questions about the “secrecy” criteria, but that’s an extreme edge case, and even then there was still some secrecy and an ongoing attempted cover-up.

Defined this way, not all conspiracies or conspiracism are either fake or bad. If I conspire with my friends to throw my partner a surprise birthday party, that’s a real and good conspiracy, assuming my partner doesn’t hate surprises. Likewise, if I notice my partner acting shifty on my birthday, it’s reasonable to think they might be up to something, making that a healthy case of conspiracy hypothesizing.

Unfortunately, generalists about conspiracy theories, and media more broadly, have used the term to either imply or outright allege that conspiracy theories are delusions arising from some cognitive defect. On the traditional view, a conspiracy theorist isn’t someone who merely advances a conspiracy hypothesis; they’re portrayed as cartoonishly credulous, wilfully ignorant, and mentally ill. Those are the features that distinguish the conspiratorially-minded from normal, healthy thinkers. Their defective minds are the main problem that must be addressed if we’re going to solve our epistemic crisis, usually through a mix of education and therapy aimed at deradicalisation and social reintegration.

Media about conspiracy theorists tends to assume the naive generalist framing, while also making the conspiracy real for dramatic effect. Take The X-Files, one of the most famous and influential portrayals of conspiracism in modern media. Mulder and The Lone Gunmen are portrayed as deviant, basement dwelling cranks with no social graces and identities centred on their pathological desire to believe. They’re also the good guys, and they’re right about basically everything. Their life’s work revealing the truth is treated as goofy but also charmingly heroic.

We might hope that media like this doesn’t actually impact people’s thinking, but Knowledge Fight and other conspiracism tracker podcasts frequently note that media is often cited as both evidence and inspiration by Alex Jones and other conspiracy theorists. My good friend Brittany Page was raised by out-and-proud nazis and she was shown They Live as a child and told that it explained the truth about Jews. I think there’s good reason for concern that media like The X-Files, They Live, and The Matrix have contributed to the dehumanising of conspiracy theorists, while paradoxically normalising conspiratorial thinking. This doesn’t justify banning media about conspiracism, but it does increase the moral obligation for artists to portray conspiracism in more realistic and sophisticated ways.

Dentith highlights several problems with the naive generalist position, but I’ll focus on two of the issues: how it begs the question, and how it downplays the current circumstances that have likely contributed to the mainstreaming of conspiratorial thinking. A person begs the question when they assume what they’re trying to prove, usually by sneaking the conclusion of the argument in amongst the premises. In this case, one major question is whether conspiracism spirals are caused by pathological minds, or whether we’re all at high risk of spiraling if we’re put in the right circumstances. Rather than argue for the claim that conspiratorial thinking is evidence of a disordered mind, generalists have simply defined it as such, based on extreme examples like Alex Jones. Thus, by definitional fiat, they assume what they were claiming to prove.

Besides being bad philosophy, this definitional pathologising of all conspiratorial thinking leads to justified pushback, simply because we’re all now painfully aware of multiple impactful conspiracies involving high ranking officials in both business and government. That was one major takeaway from the Better Way conference: they’ve gotten quite good at marshaling examples of real medical conspiracies and the harms they’ve caused to marginalised communities.

One heavily cited example at the conference was the extremely poor choice by the CIA to use the pretext of a polio vaccine drive in Pakistan to hunt down Osama Bin Laden, by running DNA tests to search for his relatives. Combining the CIA, vaccines, non-consensual DNA testing, and war on terror overreach into one real-life conspiracy was profoundly harmful, as it provides the perfect material for red-pilling potential converts. I’m skeptical that the benefits of killing Bin Laden outweigh the costs of such a damaging conspiracy.

Dismissing all conspiratorial thinking as pathological only serves to validate the concern that ‘conspiracy theory’ is frequently used as a thought terminating cliche, meant to prevent people from questioning the dominant narrative, rather than a valuable diagnostic tool. If some conspiracy theories are real, there must be some acceptable forms of thinking about conspiracy theories. If you define the concept in a way that excludes this reality, you set yourself up for easy refutation and justified blowback.

In a previous article on conspiratorial thinking, I highlighted some attempts to develop a neutral account of “conspiracy theory” and a test for distinguishing between genuine and fake conspiracy theories at a structural level, without having to assess the accuracy of the claims involved. This approach would be preferable to having to chase down each conspiracy theory, but I remain skeptical that we can come up with a formula that avoids both begging the question and pathologising belief in real conspiracies. At best, we can generate a list of red flags that should promote increased initial skepticism towards a conspiracy theory.

The red flag approach isn’t ideal, because we’re still forced to engage with the details of conspiracy theories, and that way lies the problem of “do your own research”. Particularism can’t require that we refute every single claim about steel beams or Fauci’s Wuhan lab connections before we can infer that a conspiracy theory is false and/or dangerous. Conspiracy theories are like hydras, cut down one anomaly and two more will take its place. Particularists like Dentith agree that some forms of conspiracism, like holocaust denial and great replacement theories, are both false and dangerous. Dentith has a forthcoming paper listing some additional conspiracism red flags, such as how fantastical the claims are and how likely it seems that someone could defect from the conspiracy.

These sorts of “red flag” approaches are valuable, but they don’t seem to solve the problem of “they”, which may undermine our ability to assess the evidence for any conspiracy theory. If we know that governments and other powerful entities keep secrets, how can we ever know that we have the necessary evidence to assess a particular conspiracy? For example, how do we assess what counts as a “fantastical” claim if we have to first take seriously the possibility that governments have hidden evidence of aliens and their advanced technology? The conspiracy theorist can just say our assumptions about what is “fantastical” were shaped by media controlled by “them”.

One solution could be to adjust our skepticism towards a conspiracy theory depending on how much power it attributes to the conspirators. If a theory claims that the conspirators have the power to silence “the entire medical community” or to perfectly orchestrate massive “false flag” events with no defectors, we have good reason to be skeptical of that theory. This principle overlaps with some of the red flags presented by Dentith and others, and draws some plausibility from evidence that the odds of a conspiracy being exposed increase exponentially as the number of participants goes up. In the modern world, wielding significant power requires a large network of people, so it’s reasonable to be skeptical of any theory that claims the conspirators have such extreme power.

Genuine Problems and Harmful Solutions

Improving how we talk about conspiracy theories is one key aspect of addressing the list of genuine problems that accompany antivaxxer conspiracism, especially the problem of individuals feeling dismissed and derided when they express skepticism about dominant narratives. It can also help us refocus our efforts on the external causes of conspiratorial thinking, rather than simply blaming it on faulty psychology.

The first thing I noticed after compiling the list of genuine concerns is the outsized role of America’s government and for-profit medical system. Several of the points are just symptoms of my country’s poorly regulated low-road capitalism. I don’t think this reflects a U.S. bias on my part, either, or on the part of the conference speakers. I think they correctly identify that our system is so horrible, it has extra horrible to export.

For example, growing up in 90s America, I just assumed it was normal to be inundated with television commercials pressuring me to ask my doctor about the latest medication for an illness I might unknowingly possess. Consumerism is so central to our way of life, it feels duplicitous that Jefferson changed Locke’s “life, liberty, and property” to “life, liberty, and happiness”. Jefferson was no stranger to American low-road capitalism, either, since he financed his own consumerism by developing the financing instruments that slavers used to declare their slaves as collateral for loans. In the America I grew up in, happiness was treated by many as synonymous with owning ever increasing amounts of property.

I don’t know when I first learned that drug commercials are illegal in every country outside the U.S., except New Zealand, but I vividly remember learning about the horrors of for-profit private insurance companies and their push for medication over other forms of psychological treatment. My dad is a clinical psychologist, and before I even knew how insurance worked, I knew that HMO’s, or “health maintenance organizations” are the devil. My dad would explain how these companies would take the complex, individual process of psychological treatment and demand it be boiled down to how many meetings it will take to fix the person. The companies much preferred the psychiatric medication approach, because they saw it as more quantifiable, making the profits more predictable.

Growing up in the American system, I can understand why people are skeptical of “Big Pharma”, and that’s before you get to reporting on recent crimes like unethical experimental trials by Pfizer in Nigeria. Learning about the Tuskegee syphilis study is enough to make people suspicious of medical professionals; finding out that we simply export our unethical experimentation to exploited countries could red-pill the staunchest skeptic.

Unfortunately, the policy suggestions that speakers proposed at the conference ranged from pointless to dangerous, and often seemed in direct opposition to the conclusions of their arguments. For example, after listening to relatively cogent criticisms of the U.S.’s for-profit medical system, I was baffled to hear a speaker argue for privatising the NHS, claiming that it was “bureaucracy, not medicine”. Perhaps she’s unaware of the absurd amount of bureaucracy that goes into America’s private healthcare system, or the horrors of trying to navigate multiple private systems when the stakes are unfathomably high. Unfortunately, I’m intimately familiar with the horrorshow of privatised medicine.

Eight years ago, my partner got extremely sick while we were transitioning between jobs. In two months, we racked up almost half a million dollars in medical bills, and I spent absurd amounts of time learning how to navigate our nightmare system; time that should have gone to caregiving. Due to our employer-based health insurance model, we were in a gap between insurances. We were lucky that I qualified for COBRA, an extremely expensive system that allows you to stay on your employer’s healthcare for a short period after leaving a job, but hopefully the problem here is clear. It’s a problem that starts afresh every time you move or switch jobs, and sadly the Obama administration’s attempt to set up a public insurance marketplace has not yielded an adequate alternative. So, life is just a constant struggle of trying to find doctors who will accept your insurance using outdated lists provided by unaccountable private insurance companies… and this is the improved version! Before Obamacare, private insurance would just dig up a pre-existing condition to justify denying coverage for big cost items.

Material Conditions and the Escalation of Violent Conspiracism

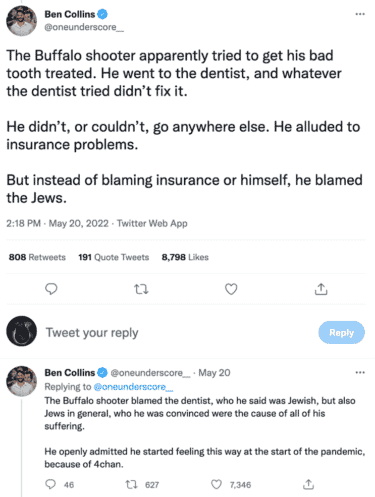

On the Saturday before the Better Way conference, there was a mass shooting in Buffalo by an individual who had been radicalised on 4chan. Reporting focused on the shooter’s manifesto, but I was also struck by NBC’s Ben Collins reporting on the “reminder” messages the shooter had been sending himself on Discord. The thread came out as I was watching the conference, and the similarities were unsettling. Collins explains that the shooter had a toothache that he couldn’t get fixed, and these comments in particular caught my attention:

Arguably, for want of basic dental care, 10 lives were lost. There are other factors of course, and guns make violence much more deadly and psychologically easier to commit. Any attempt to address the problems in America will eventually have to confront the sheer number of guns in circulation, if that’s even possible at this point. Getting rid of the guns would absolutely help, but we also need to address root causes. According to the messages, the shooter felt an increased urgency to carry out the shooting because he thought he would get proper dental care in prison.

That’s easily one of the darkest things I’ve written, and it’s a crowded field of competitors. To hijack a phrase, “guns don’t kill people, material conditions kill people”. Ideology merely provides the scapegoats. Think back to Old Dirty Bastard’s quote about Bill Cooper and the Jews:

“everybody gets fucked. William Cooper tells you who’s fucking you…”

These were the thoughts that haunted me as I watched the Better Way conference. These folks understood that there are problems, but they failed to grasp the real causes, and so end up chasing after Fauci, Gates, and Schwab. One tragic speaker explained how she had ordered a bullhorn via Amazon prime next-day delivery and then used it to protest Amazon. She earnestly thought she’d gotten the better of them. You could spend hours torturing that metaphor of the voiceless buying the illusion of a voice from a faceless org that pockets their money and never hears the message.

Even the few plans that were actionable and theoretically targeted at the problem of capitalism were still horrifying. In particular, conference organiser Dr. Tess Lawrie suggested that people need to boycott modern medication broadly speaking as a way to “hit Big Pharma where it hurts”. It’s conceivable that a massive consumer boycott could impact drug prices, but the cost in terms of human suffering would be astronomical. What we need is better regulation, not for people to stop taking their meds or getting vaccinated.

As usual, I wish I had better solutions that I could confidently offer as an alternative, but the massive, interconnected nature of these problems makes them extremely resistant to genuine fixes. Acting like the conference attendees are just too dumb to see the obvious solutions helps nobody. Like them, I feel disempowered by the system I live in, and have become increasingly disillusioned with the electoral solutions I was raised to revere. Similarly, I’m resentful of people who assume that American ignorance or stubbornness is preventing functional regulation, and ignore the structural factors that allow a White Christian Nationalist party to maintain minority rule, backed by endless piles of money and an ideologically captured Supreme Court. I feel particularly inadequate as a writer when I’m trying to convey the depths of despair I think are appropriate, given the systemic problems driving America’s spiral.

Even the act of lamenting our current crises is fraught, because it can feel like there’s no way to stop that energy from turning violent. Regarding outlooks, The Better Way speakers ranged from QAnon levels of optimism to Alex Jones levels of pessimism. Some claimed that antivaxxerism had already won and the media is just in denial, while another speaker said bluntly “we’re not winning, we’re headed towards a last stand”. That last stand mindset is a reoccurring theme in reactionary violence and stochastic terrorism. The “now or never” narrative makes it that much easier to rationalise extreme behaviour.

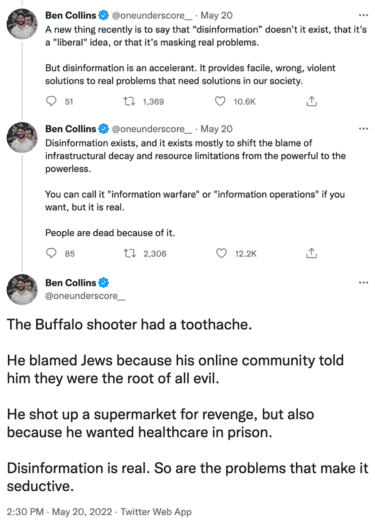

How do we press for urgency on all the reforms we need without feeding apocalyptic fears that make people more vulnerable to radicalising disinformation? The best clue I have is the end of Collins’s thread:

These tweets perfectly capture the essence of the Better Way conference, without mentioning vaccines, because it’s not about the vaccines. It’s about massive dehumanising systems that make people feel powerless, and the narratives that give them the illusion of control.