A lone drink packet under a chair at a food court in Singapore might seem a peculiar sight, but not an uncommon one. Many Singaporeans would simply treat it as the handiwork of a forgetful patron or a more devious litterbug, but most would not give it a second thought. However, the true reason behind the placement of these drinks is much more macabre: A drink placed in such a fashion is often a meal for a Kumanthong, or golden boy: simply put, the ghost of a foetus.

Voltaire said that “Superstition is to religion what astrology is to astronomy, the mad daughter of a wise mother”. According to the Association of Religion Data Archives, 97% of Southeast Asia’s population identifies with a religion, making it a diverse and richly devout space that is home to more than a handful of superstitions. Being a melting pot of cultures and religions, superstitions flow freely from one country to the next, often melding with existing beliefs to create new ones. Often these beliefs are related to bringing good or bad luck. One such belief, in infant apparitions who offer prosperity and protection, originates from Thailand and has slowly seeped into Singaporean subculture.

The belief in keeping ghost babies originates from the 19th-century epic ‘Khun Chang, Khun Phaen’ by poet Sunthon Phu. It details the morbid act of the protagonist grilling his unborn child and summoning its spirit to protect and converse with him. Despite these fantastical origins, the belief in these spirits grew widespread in southern Thailand, and manuscripts were written detailing how to create Kumanthong and their protective powers. These beliefs have spread further south since then, to the island nation of Singapore, where they have taken root in a strong sub-community that is as pervasive as it is obscure among the population. Like most idols, amulets, and trinkets, Kumanthong are supposed to bring their owners bountiful luck but only if they are taken care of properly.

My first exposure to the world of Kumanthong came during my National Service, a 2-year conscription in the Singapore Armed Forces for all male citizens at the age of 18. I initially brushed it aside as preposterous when my friend told me about our platoon commander owning a Kumanthong. When I approached him to ask about this, he told me in quite a serious tone that he did indeed have one. He would leave a can of Yakult, a flavoured probiotic drink enjoyed by children, in front of his car every day to feed his Kumanthong. Somehow, without fail, in the evenings I would notice the can had been emptied.

He also had an aversion to playing the lottery, but on the rare occasions that he did go out and buy a single ticket, he would win. Nothing major, just a minor prize of $100 or $200, but something he would credit to his Kumanthong every time. It was not enough to convince me that such a thing worked, and I chalked it down to mere coincidence, but my platoon commander certainly believed it religiously. He even claimed that if he forgot to ‘feed’ his Kumanthong he would wake up with bruises on his leg, left by the tantrum of a hungry child.

Once I learned about this, I was engulfed by the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon and began to see various cans of drinks lying everywhere in public, placed with utmost care. I noticed tiny child-like amulets and idols on the dashboards of cars that stopped next to me at intersections. It revealed an entire world and culture that I had been completely oblivious to before and showcased a side of Singapore I had never known to exist.

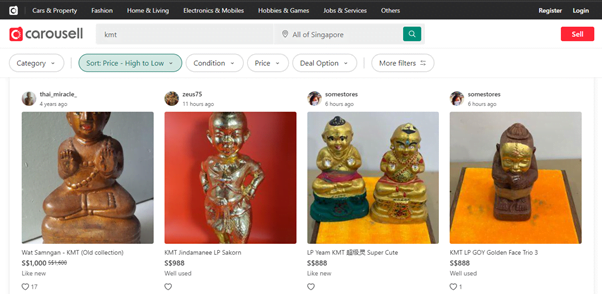

Searching the word ‘Kumanthong’ on Google will lead you down a path of forum posts or online listings of these mystical objects. Such amulets or idols can be found without any difficulty on popular local consumer and business-to-consumer marketplace, Carousell, selling for anywhere between S$100 to S$10,000 (£55 to £5,500).

If you decide to go down this rabbit hole, what you will find is hundreds of people posting about their experiences of keeping Kumanthong and how the more mischievous spirits would ‘pinch’ them and disturb their sleep at night. Others would explain how they always provided milk and toys for their inanimate amulet, to keep it happy. Although each Kumanthong story is unique, they are similar enough to prove that these are not just fictional stories, but recounts of what are believed to be real experiences by these people.

User rayzong posted his personal experience on one such forum detailing his incredible turn of luck after purchasing a Kumanthong, and a disastrous downturn after he neglected to buy any new sweets or toys for it. Other users rebuked him for not taking proper care of what essentially amounted to his child, even though he was simply a teenager at the time who had been persuaded by his friend to buy one.

Netizens also warn against ever feeding your Kumanthong blood to ‘increase its power’, as it could come at the cost of them gaining an appetite for it. Allegedly, if they do begin demanding blood, their cravings will get stronger and bad fortune will follow those unable to satiate their Kumanthong’s appetite. Acquiring a Kumanthong is as easy as buying it online, but getting rid of one is much trickier. The amulet itself cannot simply be disposed of – you must find a priest or monk powerful enough to rid them of the spirit. Those who decide to go down the path of offering what amounts to a blood sacrifice must be prepared to bear the full cost it entails.

My platoon commander spoke of his friend, Andrew (not his real name), who began feeding his Kumanthong blood so he could curse a business partner who had cheated him out of money. The business partner suffered a car accident later that month and was hospitalised, but he kept having to feed his Kumanthong with blood ever since then. When he met Andrew, he told me how the man was a shadow of his former self. He had lost excessive amounts of weight, and several scars dotted his fingers and forearms from repeated cuts and pricks. His skin had become pallid, and he talked with a lethargic demeanour – all because he felt he needed to keep ‘feeding’ his child to avoid the same misfortune from landing on him.

The common thread that runs throughout each Kumanthong story is their owners’ reasons for keeping them. Often, people procure a Kumanthong by spending a hefty sum of money for an amulet because they believe the investment will bring greater returns in the form of good luck.

Child angels

As times have changed, so has the concept of ghost babies, and while Kumanthong are still in vogue today, a contemporary has arisen: the Luk Thep, or child angel, is a variation of the concept of ghost children that also originates from Thailand. These dolls are supposedly infused with spirits via a ritual, and promise prosperity to their owners if they are well taken care of.

They grew in popularity in 2016 when doll seller, Mae Ning, conducted such a ritual, and began to sell them to celebrities who would take their Luk Thep on outings to dinners and even nail salons. One such local celebrity was radio host Thanatchapan “DJ Pukko” Booranachewawilai who attributed his career success to a Luk Thep who he lovingly named ‘Wansai’.

While initially not as popular as Kumanthong, Luk Thep mania spread to Singapore very quickly, including through Thai nationals who have emigrated here. I spoke to Vibhu, a former National Serviceman, who recounts his experience with a Luk Thep owner of he met during his time in the Singapore Armed Forces:

“My sergeant showed me a picture of his child and it was an inanimate doll”, said Vibhu. It was his first encounter with a Luk Thep and he didn’t know what to say. As dumbfounded as he was, he didin’t wish to offend his sergeant, so he acknowledged it as his child. Vibhu added, “He could tell I was taken aback and assured me that he understood how jarring it must feel”.

His sergeant had married into the tradition, as his wife was Thai and had already owned a Luk Thep that she took care of when they first met. He initially thought it was strange, but quickly got acclimatised to the idea as he began to believe the doll brought about prosperity. He even hosted a birthday party complete with cake and guests for his 1-year-old doll and showed Vibhu pictures of cake being fed to his inanimate child.

His sergeant had a few other eccentric rituals too, such as taking a cold shower and drinking a very specific isotonic sports drink immediately before his physical proficiency test, with the belief that it would allow him to score extra points. Such a mindset, coupled with his ardent belief in Taoist Buddhism, might have made it easier to buy into the belief of a spirit being held inside a doll and treating it as his progeny. When asked about the prospect of having ‘real’ children in the future, his sergeant replied that he hoped to have them someday and anticipated that they would get along with their relatively inert elder sibling.

These dolls had become so popular a few years ago that Thailand’s national police chief had to issue a notice to all checkpoints to be strict in the further inspection of the dolls. Luk Thep had begun moving through Thailand’s borders in such high volumes that they had become suspected as conduits for smugglers to sneak drugs across the border. These dolls became so commonplace in Thai culture that Thai Smile Airways, a domestic airline company, even began offering the option to buy seats for Luk Thep on their flights and instructed staff to treat them as child passengers by offering drinks and snacks to them. It made for a viral marketing campaign that attained international news coverage despite being quickly banned by the Department of Civil Aviation.

Many theories surround this superstitious belief, with some attributing the rise of Luk Thep to the low fertility rates in Thailand, while others claim the poor economy in 2016 promoted this form of animism, as people needed emotional support amidst trying times. “Child angels are a clever blend between superstition and the digital age,” said Department of Mental Health director-general, Jedsada Chokdamrongsuk, in an interview with Straits Times. Just like their progenitor, Luk Thep became a symbol of prosperity to those who needed it. However, the fad of owning these lucky dolls came to a halt as suddenly as it had begun, with many leaving behind piles of orphan dolls at temple steps on the outskirts of Bangkok.

Deeply-entrenched superstition

Ghost babies are merely the tip of the occult iceberg. Superstitions are deeply entrenched in Singapore’s roots as they influence almost everything from housing prices to eating habits. A study found that due to the popularity of numerology, Chinese residents in Singapore sought addresses ending with the number 8 as it signified prosperity and avoided those that ended with the number 4 as it meant bad luck. This led to a trend in houses with addresses ending with 8 being significantly more expensive. However, the study also noted that this could be a case of ‘conspicuous spending’, wherein buyers pay the premium on such addresses as a signal of wealth and status rather than due to superstition. Another study, conducted among health officials, noted that a vast majority had apprehensions when eating certain foods they feared would cause bad luck. Superstitions are not merely fodder for the ignorant or poor, they influence even the most educated and wealthy members of society.

The one thing most Singaporean superstitions have in common is an intrinsic belief in luck. Whether it is having a lucky home address or an unlucky food, most of these beliefs are ardently followed because there is an underlying trust that good fortune will proceed them. While there are many theories behind why such a large community exists around keeping effigies of children, luck is often the cause behind it.

The concept of luck is like any other higher spiritual force, and falls outside the realm of logical or scientific explanations. It is an explanation for those who wish to believe in it. Therefore, much like gods who are prayed to for good fortune, one can speculate that beliefs simply diverge over time. This results in them branching from revering the idol of a god in the hopes of good fortune to something like a ghost of a foetus.

So, the next time you visit this tiny island nation in the heart of South-East Asia and spot an out-of-place drink under a chair in a food court, maybe you will see the man sitting above it, gleefully grinning at his winning lottery ticket.