Books that are designed to entice people, especially young people, to appreciate science are generally a Good Thing, given the general indifference and ignorance that depletes our culture. Bernstein’s chatty style bustles us straightaway into spacetime and relativity in the very first chapter, ending with a section of bonus materials including a bit of mass-energy arithmetic yielding an energy equivalent, for a 68 kg person, of 417 years of US energy production.

Relativity dealt with, we’re ready to dive into the enchanted, entangled realm of quantum mechanics in Chapter Two. This is followed by the first interlude, a touch of atomic theory. We then strum through string theory before getting the measure of the universe.

Doctor Who pops in now and again, and there’s the odd whoosh of Starship Enterprise but more science fiction references begin to appear in the chapters on parallel worlds and powering up our civilizations, which considers the Kardashev scale of civilizations and Barrow’s alternative, inward-looking scale.

Whizzing around black holes, we hurtle through evolution, DNA and Douglas Adams before reaching genetic modification and zombies. Then it’s cyborgs, Star Wars and global warming. A large tardigrade floats past and we achieve artificial intelligence and robotics, with Roger Clarke’s extended set of Asimov’s Laws. Bonus materials: a list of celebrity science fiction robots.

With The Day the Earth Stood Still, we pause to look at extra-terrestrials and a world protocol for alien contact before embarking on interstellar travels and dwelling on dark matter. After superconductors, cloaking and sundry gadgets, we face realities and blink at the end of the world.

This very handy book also offers a glossary, notes, a reading/movie/song list and an index. Those who enjoy science fiction may well enjoy its science a lot more after reading Blockbuster Science and, for many of us, enjoying science is a way of enjoying life.

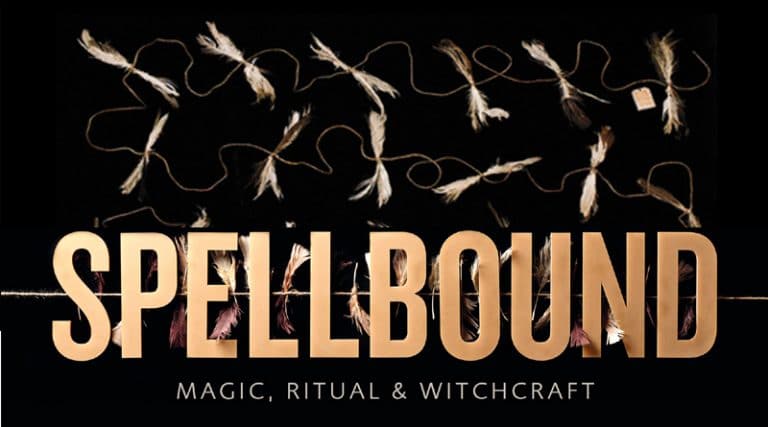

But many did not stop at protection: they used magic to perpetrate. The exhibition has a garland of feathers, a dagger-stuck poppet and a toad stuck with many thorns – all intended to cause harm by magic to others.

But many did not stop at protection: they used magic to perpetrate. The exhibition has a garland of feathers, a dagger-stuck poppet and a toad stuck with many thorns – all intended to cause harm by magic to others.