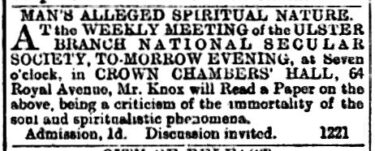

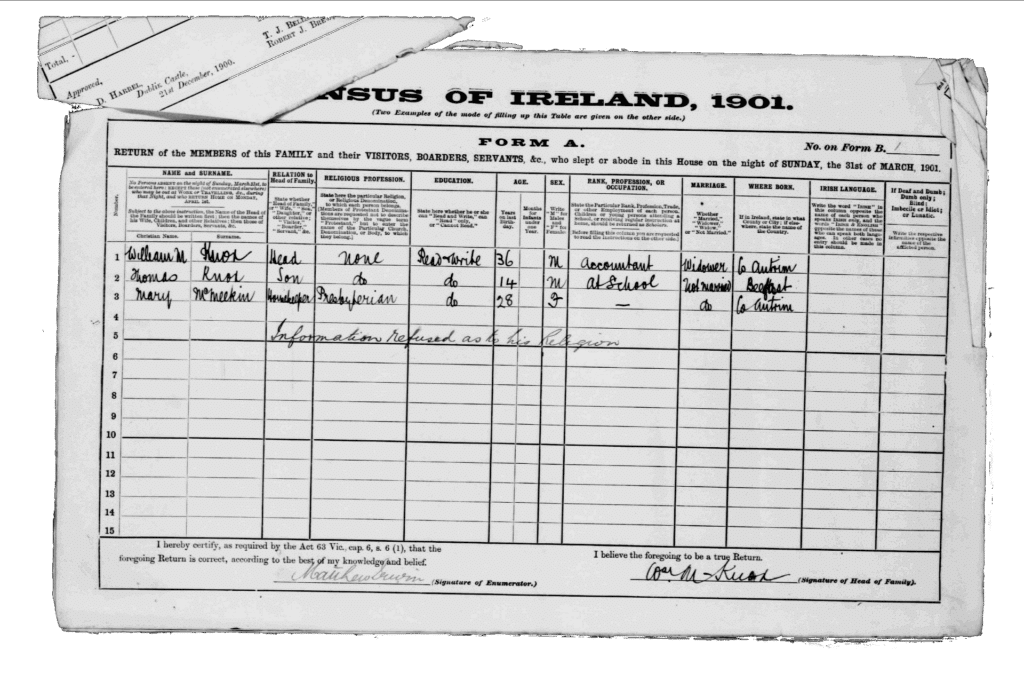

In 1892, a slim volume titled Man’s Alleged Spiritual Nature appeared from the pen of Belfast socialist, secularist, and prominent freethinker William M. Knox, then in his late 20s. The previous year, during which the Belfast newspapers advertised ‘marvellous seances’ by a Dr George André and lectures by Liverpool ‘clairvoyant and trance medium’ Miss M. Jones, Knox had read his paper before the Belfast branch of the National Secular Society.

Knox took aim at the claims of the spiritualist movement for the soul’s survival after death, and the supposed ability to communicate with a spirit world. He also challenged the arguments put forward by Alfred Russel Wallace, known for both his contributions to the theory of evolution, and his public embrace of spiritualism, which Wallace himself defined as ‘the name applied to a great and varied series of abnormal or preter-normal phenomena purporting to be for the most part caused by spiritual beings, together with the belief thence arising of the intercommunion of the living and the so-called dead’.

In the same year Knox published his pamphlet, Wallace had described how:

The universal teaching of modern spiritualism is that the world and the whole material universe exist for the purpose of developing spiritual beings — that death is simply a transition from material existence to the first grade of spirit-life — and that our happiness and the degree of our progress will be wholly dependent upon the use we have made of our faculties and opportunities here.

This idea horrified Knox, as did spiritualism’s claim to satisfy the needs of those seeking ‘proof’ of a realm beyond. Almost two decades earlier, in Miracles and Modern Spiritualism, Wallace had argued that the ‘hypothesis of Spiritualism not only accounts for all the facts (and is the only one that does so), but… is further remarkable as being associated with a theory of a future state of existence, which is the only one yet given to the world that can at all commend itself to the modern philosophical mind’ – to those now ‘imbued with the teachings of modern science’.

Knox was far from the first to level his scepticism at spiritualism, which in fact was a key part of his frustration. Time and again the claims of mediums had been revealed as false, and yet the movement continued to flourish. One contemporary writer, Lewis Thornton, described ‘spiritualistic impostors’ as being ‘just as plentiful as blackberries on a hedge, or hypocrites in Christianity,’ and for decades since the emergence of ‘modern’ spiritualism in the late 1840s, one prominent medium after another had been proved fraudulent. The appetite for the mystery and spectacle, though, was strong, as was the ability of spiritualism’s defenders to twist even apparent proofs of deception into evidence for truth.

In a history of the spiritualist movement published in 1920, leading freethinker and former Catholic priest Joseph McCabe recounted one such incident from 1877, when a ‘ghost’ – claimed to have been conjured by the medium – was grabbed and revealed to be the medium herself. ‘Her explanation’, wrote McCabe, ‘that evil powers had constrained her to impersonate the ghost while she lay unconscious in her trance, was accepted, and she continued until her next and final exposure’. McCabe added that:

Many ingenious theories were advanced by the spiritualist organs in order to prevent the complete disruption of the movement by these scandals. It was generally held that the medium had acted unconsciously, in a state of trance. Sometimes it was said that evil spirits, anxious to defeat the new religion, had possessed the unconscious medium and caused the impersonation. Others suggested that the hypnotic influence of sceptics in the circle may have automatically caused it.

It’s easy to see why such deaths by a thousand qualifications would have rankled the likes of Knox and McCabe. Even as accounts like these were published in the press, or committees convened for the purpose saw in spiritualism the ‘melancholy spectacle of gross fraud, perpetrated upon an uncritical portion of the community’ (Seybert Commission for Investigating Modern Spiritualism, 1887), the spectre remained.

As Lewis Thornton wrote in 1890, though:

common-sense may laugh at it, and science describe it as an “intellectual whoredom”… Spiritualism is a great public fact; and, however regrettable people may think it, it is as foolish to remain blind to the growth of it, as it is to ignore… the spread of the evolution theory.

This association between spiritualism and evolutionary theory was no accident. One draw of spiritualism was that it appeared to provide observable proof of a world beyond, and to enable direct communication with it, for those seeking a more ‘materialist’ basis for religion. It was a challenge to Christianity, just as Knox’s secularism was, but he saw in it many of the same flaws. Over the course of his 14-page pamphlet, Knox noted and refuted spiritualist claims one by one.

How could consciousness, so closely linked to the body in life (‘sick if the body is sick, weak if the body is unhealthy, ignorant when the body is young and limited by its capabilities’) possibly continue on after death, or, in Knox’s words, ‘at the dissolution of the tenement it has lived in’?

How could so many of the departed possibly be hanging around, considering the thousands of generations preceding ours? This was surely a recipe for serious overcrowding, assuming ‘an awful and inconceivable host of attending spirits invisibly accompanying each of us, and always yearning for us to sit around a table, turn the gas down, and ask them silly questions, so that they may tilt the table in reply.’

Why would these spirits plump for such inadequate means of communication, apparently capable only of slowly tilting a table or spelling out words on a slate? For Knox, the ‘very paltriness’ of this ‘must make such a belief deterrent to any sensible person.’

And how was it that there was such a glaring absence of meaningful discovery or revelation among these missives from the spirit world? Knox argued that in ‘all the communications from the spirit bodies there is an inherent smallness that stamps them at once as originating in this world, and among people with the limited knowledge we possess.’ Even able to defy physical laws, with access to endless time and with completely free movement, these spirits have told us nothing we don’t know. As such, he noted, ‘A living seeker after knowledge is worth a million spirits at any time!’

Knox acknowledged that for many, the prospect of annihilation was so inexplicably frightening that this fear alone could be construed as proof of life after death. But again, he pointed out the problems. How could the continuation of the soul beyond death possibly be compatible with the promise of complete happiness, when the very existence of memory would ensure the equal continuation of regrets, disappointments, and miseries? ‘It is the prospect of this never-ending consciousness’, he wrote, ‘that appals me’.

Above all else, the implications for practical human life dismayed Knox. To accept the claims of spiritualism, he argued, credulity was a requirement: ‘a passive frame of mind’ and the maintenance of harmony among seekers were necessary to receive the medium’s messages, and made believers ‘apt to ignore the evidence’. This meant ‘the abandoning of criticism’ and the ‘unquestioning acceptance’ of spiritualists’ explanations: anathema to the freethinker.

So too was the explanation for the problem of evil, which for Wallace was the means by which mankind could develop the higher moral attributes necessary to earn a permanent spiritual existence. To Knox, this was clearly a recipe for inaction. ‘Is it not a horrible thought that all the evil in the world is necessary in order that good may exist at all?’ he asked. Surely the ‘necessary result of such an argument is that we should not attempt to combat evil, for, if it is banished, then good will cease.’

This was also an inadequate basis for morality; a false altruism. If goodness was only practised with a view to rewards in the hereafter, it wasn’t for others’ benefit at all. ‘This,’ Knox argued, was ‘the rock on which all creeds have been wrecked.’

For Knox, who believed firmly in social action, this was the crux of the issue, and the root of his secularism – the latter being, in the sense intended by George Jacob Holyoake who coined the term, an earthly, humanist philosophy rooted in working for the betterment of the world during the one life you could be certain of. Morality must be untethered from superstition and rooted in real life:

The basis of ethics must be shifted from a shadowy world peopled with the imaginings of credulity. We live in a practical work-a-day world, and the good we do will result in substantial benefit here… the following of virtue will promote good in this world and make the virtuous more happy, as well as adding to the happiness of others.

Four years after the publication of his pamphlet, Knox would go on to co-found the Belfast Ethical Society, which emphasised ‘the promotion of right conduct on a purely natural and human basis and the intellectual advancement of its members’, as well as ‘the development of character, independent of theological speculations.’ They held lectures on science, literature, and social questions, providing a forum for discussion and debate, and were affiliated with the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK).

Knox was also Secretary of the National Secular Society’s Ulster Branch, and of the Belfast Radical Association, actively involved in the Belfast Debating Society, the Belfast and District Workers’ Educational Association, the Belfast Co-operative Society, and the local branch of the Independent Labour Party. He was connected with the activities of the Cinderella Club, which provided opportunities for children living in poverty to experience good food and entertainment. Knox was no mere hater: he saw spiritualism as one more barrier to progress, one more distraction from the matters at hand.

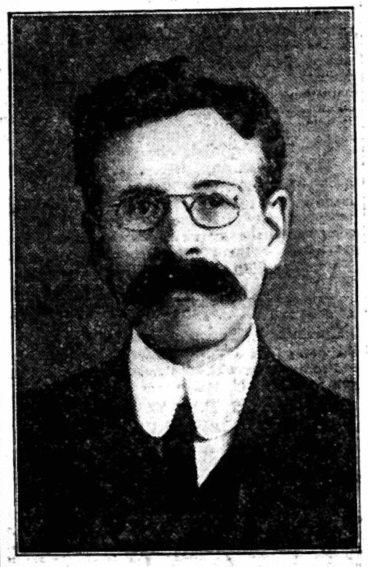

Knox was described in the memoirs of Belfast-born writer James H. Cousins as ‘a one-eyed propagandist of atheism and socialism’. Whether he literally had the use of only one eye, or whether Cousins’ implication was a laser focused, even blinkered, propagation of his causes, is unclear, but it’s quite an image. If it was the latter, there can be no doubt as to his lifelong preoccupations.

Knox, a poet and lover of literature, concluded his pamphlet with a paraphrase of George Eliot who, ‘speaking of God, immortality, and duty said, of the first we have no knowledge, the second is wrapped in mystery, but the third is clear and bright and before each of us.’

Only in the knowledge of having done our best in this life can we go contentedly into nothingness, or off into the next. Why tie ourselves in knots to prove the existence of something other, when the world is right here?

Man’s Alleged Spiritual Nature was found and photographed in the collections of the Linen Hall Library, Belfast, by Iain Deboys of Northern Ireland Humanists, following research into the Belfast Ethical Society and its key figures.