In April 2025, a team of astronomers announced that they might have found indirect evidence of life on an extraterrestrial planet. This planet – K2-18b – had been known as a sub-Neptune of about 8.5 Earth masses located in a habitable zone of its ‘sun’, a red dwarf K2-18. Moreover, its atmosphere was likely to contain water vapour; this fact held out a hope of the presence of liquid water on its surface.

That time, analysis of James Webb Space Telescope observations highlighted a faint signal that might be caused by the presence of dimethyl sulfide in the atmosphere of the sub-Neptune. This is a volatile organic compound with a simple structure – nothing in common with DNA, proteins or more complex molecules which would really require a strong explanation. But there is just one thing: on Earth, it is used as a convenient proxy for microbial activity in aquatic environments since it is produced solely by certain microbes in earthly conditions. This fact encouraged the researchers to carefully suggest that this faraway world might actually host life.

Extensive media coverage of this topic created an impression that it is not only a possible hypothesis but a firm discovery of life on the other planet. Meanwhile, researchers debate on whether the dimethyl sulfide was real. Its peak was not only faint – it could be explained by tens of other substances which are able to arise abiotically. After an in-depth analysis, scientists are not so sure that K2-18b is inhabited. The assumption of its habitability has also been challenged. Κ2-18b now seems to be an example of so called scientific covery – a dispelling of false or misleading notions about a discovery.

In astrobiology, compounds like dimethyl sulfide are a particular case of so called biosignatures – observations that indicate the presence of life with high probability. Specifically, this is a putative atmospheric biosignature – which could be defined as a specific atmospheric component highly suggestive of life.

Atmospheric biosignatures are almost the only type of biosignatures we can identify on exoplanets – because only atmospheres produce a unique spectral fingerprint by interacting with the light of the star when passing before it. But the case of K2-18b exposes the vulnerability of such biosignatures – from the biological point of view, such data are extremely insufficient to prove the presence of life.

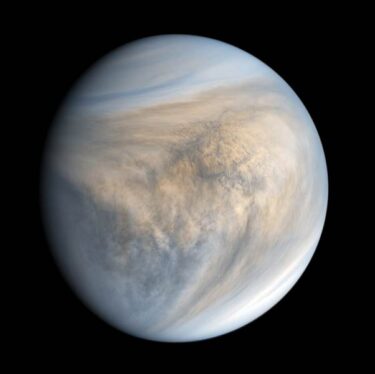

Venus – one of the nearest planets to the Earth – is one more example of this insufficiency. Venus is visible on the sky as a bright morning star, and its atmosphere is visible upon its transit before the Sun even through a simple telescope. That is how the Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov spotted the Venusian atmosphere for the first time. Its spectroscopic signal is much stronger than those from the faraway exoplanet’s atmosphere. We could expect that we are able to examine the Venusian atmosphere at its most elemental – and there will be no controversies regarding the possible biosignatures. But Venus recently told another story of a scientific covery.

In 2020, an international group of scientists from the UK and the USA reported the detection of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus. This gas, having the chemical formula PH3, contains the most reduced state of phosphorus, which is unlikely to be stable in the Venusian atmosphere.

The thick clouds of Venus, which reflect the sunlight and provide its brightness, consist of almost pure anhydrous sulphuric acid. You really don’t want to touch this reagent even on Earth, in the test tube. Apart from the fact that this is one of the strongest acids, it is one of the most potent oxidizers. Venusian clouds contain this acid in small droplets, which increases the reaction surface and creates the ideal condition to burn out any compound with reducing capacity. So, the fact that phosphine is still present shows that something – or somebody? – is producing it, and replacing its chemical loss. But what, if not life?

It was really tempting to suggest the presence of life as the only possible explanation. However, at least one alternative scenario is possible. One year later, new modelling results were published which show that volcanic activity on Venus might supply the necessary amount of phosphine to replenish its atmospheric pool. This means that no life is necessary to explain the observation results.

This case details the vulnerability of atmospheric biosignatures: we can only find that some compound needs to be constantly replenished, but we cannot say for sure that it must be replenished by living things. Moreover, we cannot find any chemical biosignature which necessarily implies the presence of life – because we have no astrobiological definition of life in chemical terms.

The biochemistry of life on Earth is known in detail, but in astrobiology, we must consider the possibility of alternative biochemistry. Can we develop a definition of life which covers all – or at least the majority of – alternative biochemistries? It seems that we can – but it inevitably goes beyond any chemical information and gives no clues about which chemicals to search for. The official definition by NASA goes: “Life is a self-sustained chemical system capable of undergoing Darwinian evolution”. There are numerous other definitions, but all of them follow the same approach – no specific chemistry, only physics and emergent properties like – for example – evolution.

There is no specific set of chemicals whose presence would imply such definitions have been met; moreover, there is no chemical sign of evolution or reactions being self-sustaining. We could use only the nearest proxy of self-sustaining – a constant production of some compound. But this approach, like in the phosphine example, might be misleading.

Could we narrow our search and connect life in general with specific chemical patterns it produces? To do this, we should know which hypothetical types of biochemistry are possible and which are not – but we don’t know. Some biosignatures are in fact inspired by the Earth-type biochemistry – including the cases of dimethyl sulfide and phosphine. However, if we narrow our search this way, we need to explain how Earth-type life can survive on sub-Neptunes or hellish sulphurous planets like Venus. This, in turn, decreases the strength of the hypothesis. I might say that we cannot find reliable signatures of life because we don’t know what life is – like in the case of discovering non-human languages I discussed here before.

Such considerations lead the scientific community to gradually give up on observational biosignatures and postponing the questions on life on other planets until we have samples for laboratory investigation. In this regard, a recent case of “leopard spots” on Martian rocks is remarkable. The patches on Martian rocks spotted by the Perseverance rover in the Jezero crater strikingly resemble the traces of redox reactions which are attributable to microbes in the Earth conditions. However, in the abstract of their formal publication in Nature, the authors of the discovery state:

Ultimately, we conclude that analysis of the core sample collected from this unit using high-sensitivity instrumentation on Earth will enable the measurements required to determine the origin of the minerals, organics and textures it contains.

Maybe some of my colleagues will see here only a careful academic wording; however, I see the shift of the expectations and methodology. We still have no technical solution to deliver samples from Mars to Earth – to do this, we should obtain fuel from local resources on Mars launch the spaceship toward Earth only by remote commands. The prospect of having Martian samples here on Earth remains elusive; however, the scientists preferred to postpone definitive conclusions till that moment in the future.

I suggest that this signals the end of a ‘biosignature boom’ which we could see in the first years after starting extensive exoplanet observations. Researchers are gradually disappointed in the idea of searching for life only by one physical marker or – in the best case – by photos of the rocks. Now they need to literally run their hands over the alleged extraterrestrial life – even if they have to wait for a long time.

Cover image: Artistic representation of the planet K2-18b. Credit: NASA / ESA / CSA / Joseph Olmsted / Public Domain