On 14 November, headlines circulated around corners of the internet, proclaiming: “HUGE: Norway SUSPENDS Bovaer Use in Cows.”

The accompanying article stated that Norsk Melkeråvare, Norway’s largest dairy supplier, had suspended the use of the feed additive Bovaer, following reports from Danish farmers alleging it caused illness and collapse in cows. It also referenced Denmark’s decision to mandate methane-reducing feed additives for all dairy cattle, in herds of fifty or more cows.

The claims from the Danish farmers spread rapidly online, prompting concerns about both animal welfare and food safety. Meanwhile, in the UK, dairy producer Arla announced they would be running a project to introduce Bovaer:

…a product that has been researched for over 15 years and is already used in many countries around the world… Our UK projects on methane-reducing supplements have now ended, and the findings are currently being reviewed.

We are yet to hear the findings of this project.

To understand the wider context, we need to examine why methane inhibitors like Bovaer exist, how they fit into climate policy, whether there are better options, and what scientific evaluations actually show.

Why Focus on Emissions From Dairy Farming?

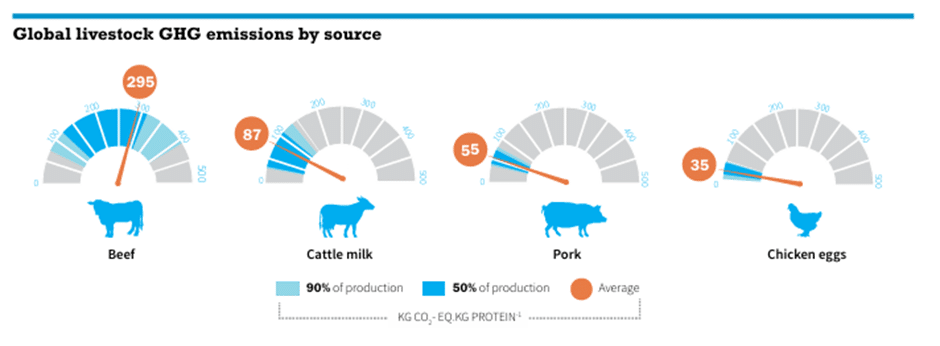

The global dairy sector provides essential nutrition, supports millions of livelihoods, and underpins rural economies. However, livestock farming contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, including CO₂, nitrous oxide, and methane. In examining the ‘environmental impact’ here, we will focus on the greenhouse emissions, rather than the other environmental impacts we can see in agriculture.

Global estimates suggest that livestock farming contributes between 16.5% and 28% of total greenhouse gas emissions. Across the EU, agriculture is the largest methane-emitting sector, responsible for 56% of methane output. In 2020, enteric fermentation in cattle accounted for 67% of agricultural methane emissions.

Despite reductions between 2000 and 2021, agriculture still represents around 11% of UK greenhouse gas emissions, 71% of UK nitrous oxide emissions in 2021, and 49% of UK methane emissions in 2021. In contrast, agriculture only accounted for about 2% of total carbon dioxide emissions in the UK. Within the dairy sector specifically, enteric methane – distinct from methane produced from manure – accounts for an estimated 47-59% of all carbon emissions.

As global populations grow, food systems must deliver security and efficiency, while reducing environmental impact. Many nations are therefore adopting climate-tech solutions, including robotics, precision agriculture, improved genetics, and the introduction of feed additives designed to reduce emissions per unit of food produced.

Some countries have opted for drastic action. In the Netherlands, more than 750 farmers accepted government buyouts in 2023 to reduce nitrogen emissions, with more expected to follow. Other countries, such as France, argue that reducing domestic production could simply shift emissions abroad, worsening global outcomes. In order to keep up with demand for food and a growing population, sustainable intensification – producing more with fewer emissions – is increasingly viewed not as an option, but a necessity.

The Debate Around Methane Inhibitors

Amid this landscape, methane-reducing technologies such as Bovaer have received significant attention. Bovaer (3-NOP) is designed to suppress methane formation during digestion, reducing emissions from cows.

However, those viral posts claimed that Danish cows fed Bovaer have become seriously ill or died, describing the product as “poison”. Videos and anecdotal testimonies have circulated on social media citing collapse, diarrhoea, infertility, reduced milk yield, and risks to human consumers. Such claims require careful examination against scientific evidence and regulatory assessments.

In 2021, the FEEDAP Panel of the EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) concluded that Bovaer is safe for dairy cows at the recommended dose of 100mg 3-NOP per kilogram of dry feed matter. No safety concerns were identified for consumers or the environment, though the additive may irritate skin, eyes, or be harmful if inhaled in its pure form, emphasising the need for PPE during manufacturing or handling before mixing.

Bovaer was found to be effective in reducing enteric methane emissions when fed at 53-60 mg/kg of complete feed, and while a margin of safety was not established for other ruminant categories, this was due to insufficient data, not because of identified harm.

In 2021, the UK FSA released a position paper, including a summary by Natasha Smith, Deputy Director of Food Policy, which concluded that milk and meat from animals fed Bovaer are safe for human consumption. The additive was found to be fully metabolised by the cow, and did not pass into milk, with more than 58 studies showing no carcinogenic or genotoxic effects, even at double the recommended dose.

In terms of animal and worker safety, there were no adverse effects observed in cattle at approved doses, and Bovaer was found not to be harmful in the form fed to animals.

How effective are methane inhibitors?

A review compiled data from 78 peer-reviewed in vivo studies conducted over the past five years, focusing on ten different methane inhibitors, demonstrated a 5% to 75% reduction in daily methane emission, 2% to 70% reduction in methane yield, and 11% to 74% reduction in methane intensity.

Among the inhibitors, macroalgae are the most effective, achieving 22% to 75% of methane reductions, followed by small targeted molecule inhibitors 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP, marketed as Bovaer) with 13% to 62% of methane reductions. A meta-analysis found that 3-NOP reduces methane emissions from cows by around 31–33% when fed at typical doses.

However, the effectiveness of 3-NOP depends heavily on what the cows are eating. Two main dietary factors reduced how well 3-NOP worked: high fibre, and high fat. The more fibre in the diet, the less methane reduction was achieved. Similarly, in high fat diets, increased fat content lowered how effective 3-NOP was. Higher doses of 3-NOP improved methane reduction, and lower fibre and lower fat diets allowed 3-NOP to work better. For example, reducing dietary fibre by just 1% (10 g/kg dry matter) increased the methane-reducing effect of 3-NOP by nearly 1%. Reducing dietary fat by the same amount increased its effectiveness even more – by just over 3%.

In another study, researchers looked at how different amounts of 3-NOP affect feedlot beef cattle. Bulls were fed Bovaer at 75 mg/kg of dry matter of feed – “Bovaer 75” – or at 100 mg/kg of dry matter of feed – “Bovaer 100” – or a control feed with no Bovaer.

It found that feed intake stayed the same across all groups, meaning that 3-NOP did not make the animals eat more, nor less. Bulls fed Bovaer 75 grew faster than both the control and higher-dose group (1.73 kg/day vs. 1.63 and 1.60 kg/day), and these Bovaer 75 cattle were also more biologically efficient, meaning they needed less feed to produce the same amount of carcass.

Both Bovaer doses in the study significantly reduced methane emissions – a 33.7% reduction with Bovaer 75, and a 42.7% reduction with Bovaer 100. Those methane reductions held true whether adjusted for feed intake, weight gain, or efficiency. The study also found that as methane went down, the bulls produced more hydrogen – which is expected, because 3-NOP shifts how the animals ferment feed in the stomach.

The researchers concluded that feeding Bovaer to cattle consistently lowers methane emissions, with greater reductions at higher doses. The moderate dose – 75 mg/kg – also improved growth rate and feed efficiency, showing that reducing emissions can go hand-in-hand with maintaining or even improving cattle performance.

If not methane inhibitors, then what?

Clearly some critics of using food producing animals – or any animal products – would say that complete abstinence from milk and meat consumption would also reduce the current negative impacts of ruminant greenhouse gas emissions. However, with a growing world population, is it sensible, or even possible, for individual nations to sacrifice their livestock farmers for the environmental benefit, especially if the adoption of technology could help achieve the same outcome? According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations:

Livestock are key to food security. Meat, milk and eggs provide 34% of the protein consumed globally as well as essential micronutrients such as vitamin B12, A, iron, zinc, calcium and riboflavin. But their contribution to food security and nutrition goes well beyond that, and includes a range of other goods and services, such as animal manure and traction. Hundreds of millions of vulnerable people rely on livestock in a changing climate, because of animals’ abilities to adapt to marginal conditions and withstand climate shocks.

In 2021, agriculture contributed around 0.5% to the United Kingdom’s economy. Agriculture provided half of the food the UK ate, and employed almost half a million people, as well as being a key part of the food and drink sector. In 2021, farmers and land managers managed 71% of the UK’s land.

A relatively small population of high-performing dairy cows produces around 45% of the world’s milk, while more than half of all dairy cattle are raised in low-intensity production systems. Even within a small country such as the UK, agricultural practices vary widely across regions, highlighting the need for tailored sustainability strategies rather than a one-size-fits-all solution.

What other solutions are there?

In the absence of complete withdrawal of use of animal products, we must continue to work towards reducing the environmental impact while balancing health and welfare, food safety and yield. There are a variety of tools available to farmers to evaluate the environmental impact of their farm. For farmers in the UK, the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board provides a guide for choosing a carbon footprinting tool.

Changes are not always as simple as they seem, as we balance benefits to the environmental impact with animal welfare, food safety and yield. Increasing proportions of dietary concentrates – thereby reducing the quantity of forages fed – could potentially reduce emission intensity by 15%. However this must be pursued with caution, as high – equal to or more than 40% – proportions of dietary concentrates increase the incidence of digestive disorders and digital dermatitis, both of which will reduce the overall feed efficiency of the animal and lower welfare.

Direct manipulation of the rumen microbiome to reduce the quantity of methane produced has been trialled with many different compounds, but can have significant toxic or environmental issues associated with them. Commercially available products that intervene in the rumen fermentation process are available, and although health risks to humans of antimicrobial resistance caused by use in agriculture have been considered low, recent evidence suggesting co-selection for vancomycin resistance has led to calls for further investigation.

Most significantly, healthy livestock produce fewer emissions per kilogram of meat or litre of milk than unhealthy animals. This is because their feed conversion ratio and fertility is better, and there are fewer losses resulting from poor performance, mortalities and involuntary culls. A 10% reduction in livestock disease would eliminate 800 million tonnes of greenhouse gases each year. Impaired health has negative impacts on livestock system production efficiency. Thus, including health and welfare traits in the selection of breeding stock that improve resilience to disease, and engaging in herd health plans and agritech to monitor and pick up disease quicker is imperative.

Conclusion

Clearly, this is a national and international strategy that is far too nuanced to cover in any meaningful detail in one article, however much we would like to try. Methane inhibitors like Bovaer exist within a broader effort to reduce agricultural emissions while maintaining food security.

Although many countries have been using, or at least trialling, methane inhibitors – such as the US, Europe, Southeast Asia, Africa, Brazil and the UK – Denmark has been one of the first to adopt and mandate these interventions, and as such has also been the first to experience the concerns surrounding its use.

Although social media has amplified anecdotal reports, extensive scientific evaluations from multiple international regulators consistently conclude that Bovaer is safe for cows at approved doses, and that milk and meat from Bovaer-fed animals are safe for humans. Evidence also demonstrates that Bovaer reduces methane emissions, while environmental and consumer risks are minimal when handled correctly.

Therefore, although there are numerous other strategies for reducing the overall environmental impact and greenhouse emissions in agriculture, many of which could even be considered superior to the use of methane inhibitors, at present data suggests methane inhibitors are a viable and safe option for some to reduce methane emissions.

References

- Middleton, M. (2023) Counting Carbon; Does a Smaller Footprint Leave Less Impact? Defining Sustainability in the Dairy Sector.

- Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental issues and options, fao.org/3/a0701e/a0701e.pdf PAGE 112

- Area twice size of UK needed to feed world’s pets | The University of Edinburgh

- Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Fertiliser Production – International Fertiliser Society (fertiliser-society.org)

- Estimation of methane emissions from the U.S. ammonia fertilizer industry using a mobile sensing approach | Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene | University of California Press (ucpress.edu)

- Acceleration of global N2O emissions seen from two decades of atmospheric inversion | Nature Climate Change

- Greenhouse gas emissions from soils—A review – ScienceDirect

- A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010–2050 | Nature Food

- Carbon Footprint: The Case of Four Chicken Meat Products Sold on the Spanish Market – PMC

- PBL publiceert quickscan van twee beleidspakketten voor het vervolg van de structurele aanpak stikstof | Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving

- Netherlands proposes radical plans to cut livestock numbers by almost a third | Greenhouse gas emissions | The Guardian

- Bovaer cow feed additive explained – Food Standards Agency

- Fact check: Are cows in Denmark dying over Bovaer additive? | Euronews

- Safety and efficacy of a feed additive consisting of 3‐nitrooxypropanol (Bovaer® 10) for ruminants for milk production and reproduction (DSM Nutritional Products Ltd) – – 2021 – EFSA Journal – Wiley Online Library

- Special Report on Climate Change and Land — IPCC site

- Sustainable Food & Farming Factsheet for Farm Vets —Vet Sustain

- Environmental sustainability and ruminant production: A UK veterinary perspective – Britten – 2025 – Veterinary Record – Wiley Online Library

- Livestock solutions for climate change

- A meta-analysis of effects of 3-nitrooxypropanol on methane production, yield, and intensity in dairy cattle – PubMed

- PSXIV-3 3-Nitrooxypropanol Dosages to Reduce Methane Emission By Feedlot Beef Cattle | Journal of Animal Science | Oxford Academic

- Danish initiatives to lower emissions

- Cattle Methane Inhibitors: Progress and Next Steps | World Resources Institute

- Mitigating enteric methane emissions: An overview of methanogenesis, inhibitors and future prospects – ScienceDirect

- Cattle health planning to reduce emissions | AHDB

- Improve animal health to reduce livestock emissions: quantifying an open goal | Proceedings B | The Royal Society

- Agri-tech: will technology help or hinder food production and animal welfare?