Sometimes it feels like everyone on the internet thinks they’re experts on the latest big issue. Whether it’s vaccines, immigration, the economy, or AI, people with actual professional qualifications and experience find their educated opinions challenged by amateurs who “do their own research”.

But what if we gathered a group of those non-experts together, and were able to aggregate their collected opinions? Could the result ever be as accurate, or even more accurate, than a genuine authority on the subject? After all, in Politics, Aristotle said, “It is possible that the many, though not individually good men, yet when they come together may be better, not individually but collectively, than those who are so.” On the other hand, in Men in Black, Agent K said “A person is smart; people are dumb, panicky, dangerous animals.” So, who’s right?

The answer, as is true for all the best questions, is “it depends”.

In 1906, Charles Darwin’s cousin, Sir Francis Galton, visited the West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition in Plymouth. One of the attractions was a competition where, for a fee of sixpence, visitors were given a numbered card, on which to write their guess as to the weight of an ox, with the closest guesses winning a prize.

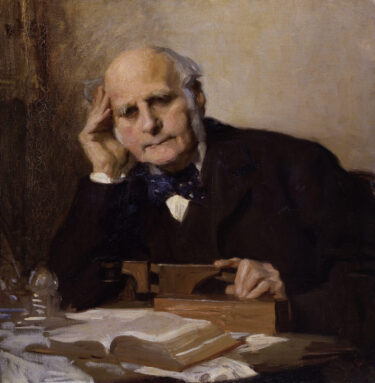

As one of the leading statisticians of the Victorian era, Galton saw the opportunity for an experiment and borrowed the cards from the organiser. He saw this as analogous to the idea of democracy by popular vote, writing in Nature: “the average competitor was probably as well fitted for making a just estimate of the dressed weight of the ox as an average voter is of judging the merits of most political issues on which he votes.” This was not a compliment. Aside from his considerable academic achievements, Galton was also a prominent early eugenicist (in fact, he coined the term in 1883), and took a dim view of those “average” voters.

Galton placed the 787 legible guesses in order and found that they formed a skewed bell curve, with a quarter of the guesses overestimating the weight by 45 pounds or more, and another quarter underestimating it by at least 29 pounds. The median (which he called “middlemost”) guess was 1207 pounds, which was less than 1% off the true weight of the ox, which he reported was 1198. He described this result as “more creditable to the trustworthiness of a democratic judgement than might have been expected.”

Following a letter to the editor of Nature suggesting the mean would have been a better measure than the median, Galton wrote that the mean guess was in fact 1197 pounds, which is remarkably close. In fact, a 2014 paper reexamining the data shows that the true weight of the ox was misreported in Nature due to a transcription error, and the weight, according to the competition organiser’s original letter, was 1197 pounds – exactly the same as the mean of all the guesses.

This principle has been replicated in many studies over the years since. In 1924, Kate Gordon filled ten identical glass bottles with similar amounts of lead shot and cotton. The lightest was 16 grams, and they increased in weight by increments of just 0.16g. She then had 200 students attempt to place them in order of weight. With such small variation, this was very hard, and only 85% of the students could even correctly order the lightest and heaviest. She then calculated a coefficient of correlation for each student’s attempt with the correct order. A perfect answer would give a result of 1, and getting them in reverse order would give a result of 0. The mean correlation of all their individual attempts was 0.41.

Gordon then randomly grouped the students and averaged the positions they assigned to the bottles. Placing them in groups of five raised the mean correlation to 0.68. For groups of 10, it was 0.79; for groups of 20 it was 0.86; and for groups of 50 it was 0.94. In other words, even small groups outperformed the average individual, and the judgement improved with group size. Multiple experiments have shown similar results in everything from guessing the number of jellybeans in a jar, to predicting the outcome of Canadian elections, or the number of gift cards sold at Best Buy.

The theory of how this works is that, in the absence of biases, people are likely to be wrong in both directions. If roughly the same number of people overestimate something as underestimate, and in roughly the same magnitude, then those errors will cancel out and the mean or median result will be close to the truth.

Of course, biases are rarely absent, and it’s in those biases that we find the limitations of the wisdom of crowds. Some biases are cognitive or perceptual – for example, humans tend to underestimate how many items we are looking at when the number is large. Other biases may be introduced by the way group decision-making is set up.

In each of the prior experiments, the individuals made their decisions independently, and their results were then averaged. However, if that independence isn’t maintained, and groups are allowed to confer – or even if individuals are shown previous guesses – group members will influence each other, resulting in a narrower range of answers. This lack of variance means that the larger errors don’t get cancelled out, and the accuracy of the average answer drops. At the same time, the individuals’ confidence in the accuracy of their answer increases.

An effective way to reduce this kind of bias is to ensure there is diversity within the group; not social or cultural diversity, but diversity in perspective and cognitive approaches to the problem. If everyone in the group has the same areas of expertise or solves problems in the same way, the quality of their decision-making suffers. By contrast, when a diverse group is randomly selected from a large pool of intelligent problem solvers, they can outperform a group made up of the best-performing individuals.

The wisdom of the crowd appears to work best when applied to questions with a simple binary or numerical solution, to which there is an objectively true answer. Aside from the fact that this format makes it easy to apply statistical averages to the individual responses, when complex problems require creative solutions, the ability of groups to work together to combine ideas and expertise often surpasses what each individual can bring to the task.

Finally, in areas where specialist knowledge or training is available, there’s no evidence that suggests listening to the crowd instead of experts is best. Epidemiologists know more about vaccines than the largest crowd of diverse, independent, non-experts, and if you find an unexploded WW2 bomb, you should call the authorities – don’t go on Quora to see what they reckon.

In the end, the wisdom of crowds is an interesting way to reduce statistical noise in very specific circumstances, but perhaps the real wisdom is in knowing when, and when not, to rely on it.