Movement is really good for us – all physical activity contributes to our health and wellbeing. It helps improve mood, increases bone density, helps regulate blood sugar, increases cardiac function, and reduces the risk of many diseases. But what happens when the primary motivators for many – weight loss and muscle gain – become easily achievable through alternative means?

As an exercise scientist, I have consistently been struck by the profound impact of physical activity, extending beyond the prevention of lifestyle diseases. For example, long-term studies, tracking individuals across their lifespans, reveal a striking reality: being in the bottom 20% for fitness is comparable to smoking a pack of cigarettes per day.

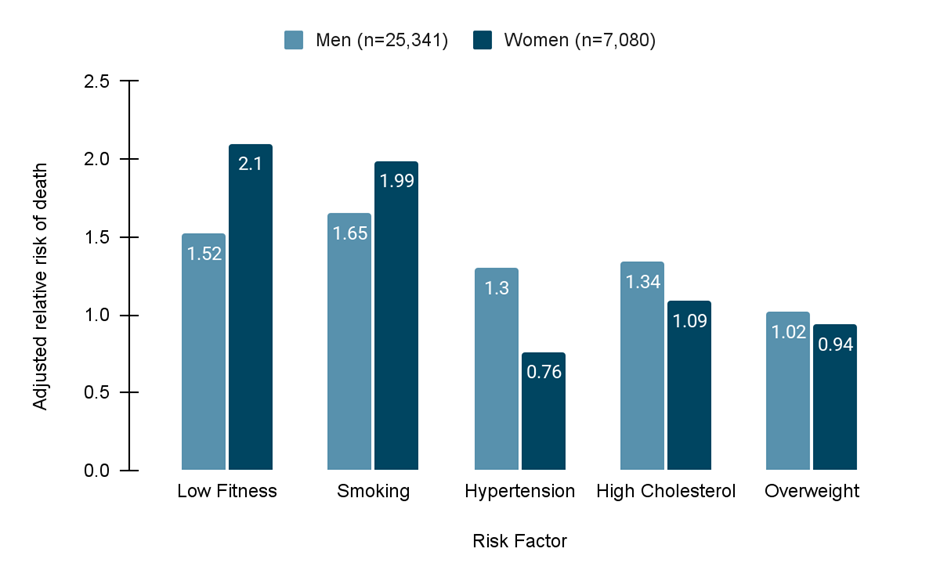

Risk factors established by the Aerobics Centre Longitudinal Study show low physical fitness was associated with an equal or greater risk of all-cause mortality of other known risk factors.

Low fitness: The least fit 20% of the participants as measured by their ability to intake oxygen (VO2 Test)

Smoking: Self reported current or recent smokers

Hypertension: Systolic blood pressure greater than 140mm Hg

High Cholesterol: Total cholesterol greater than 6.2mmol l-1

Overweight: Body mass index greater than 27kg m2

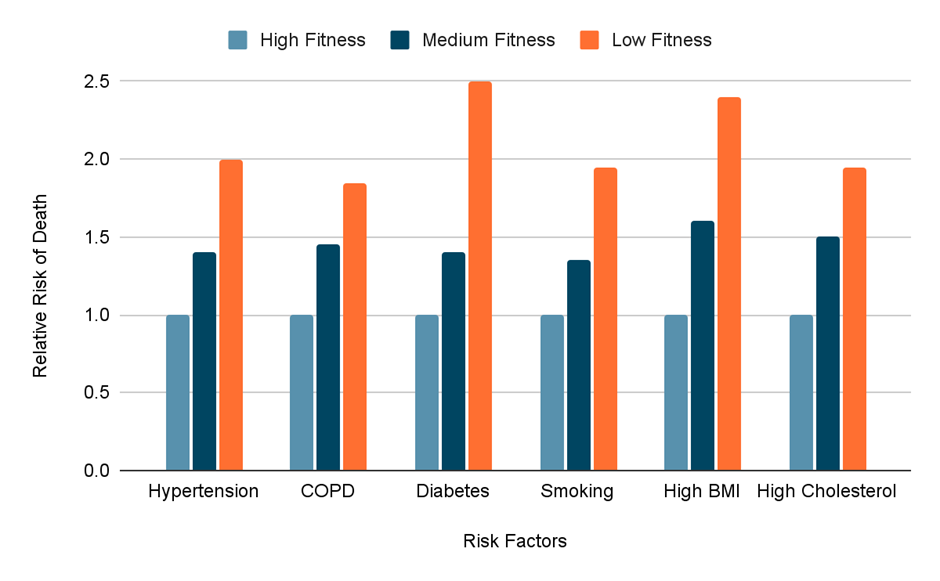

Furthermore, maintaining higher fitness levels offers significant protection against all causes of death in older age, even in the presence of common risk factors, such as high cholesterol, hypertension, high BMI, smoking, diabetes, and COPD.

A study of Californian men shows increased exercise capacity is associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, even in the presence of established risk factors.

Hypertension, COPD (Cardio-obstructive pulmonary disease), and diabetes: As reported diagnosed in their medical records.

Smoking: Self reported current smokers

High BMI: Body mass index greater than 30kg m2

High Cholesterol: Total cholesterol greater than 5.7mmol l-1

Physical activity and body weight are often conflated in discussions surrounding health. “Move more, eat less” has served as the simple mantra championed by health experts. This mindset, while acknowledging that energy balance is fundamental to changing body composition, reduces every mile run and weight lifted to an entry in a calorie ledger. This transactional view of physical activity, though perhaps well intentioned, has often turned physical activity into a chore – a necessary penance for dietary transgressions, rather than an enjoyable and integral part of a healthy life.

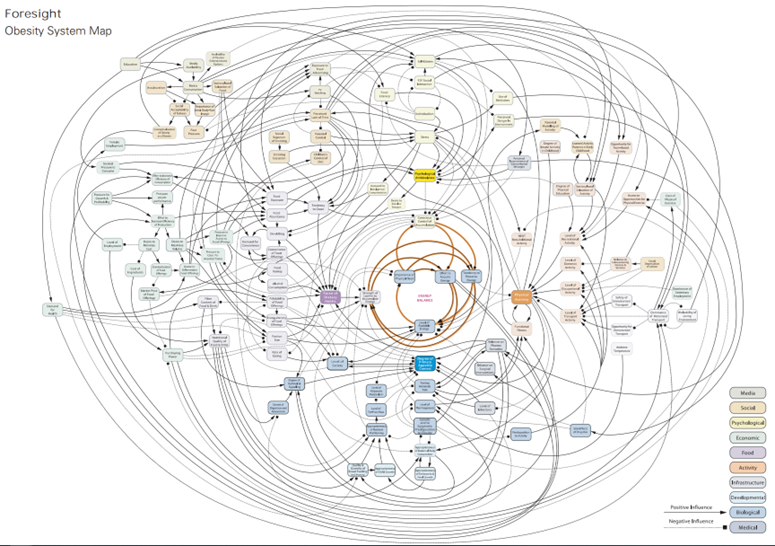

Moreover, by anchoring physical activity so firmly to weight loss, we’ve inadvertently constructed a moralistic framework rooted in willpower and self-control, overlooking the complex biological, genetic, and environmental factors that influence energy intake and expenditure.

However, the tectonic plates of weight management have shifted. The advent of pharmacological interventions, particularly the GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic and Wegovy) and tirzepatide (Mounjaro), offer a powerful new method for achieving weight loss by primarily targeting energy intake. These medications work by mimicking gut hormones that regulate appetite and satiety (fullness). Scrolling social media reveals numerous reports of users experiencing significant reductions in appetite (often termed ‘food noise’) and a greater sense of fullness after consuming smaller meals.

Unlike many past weight-loss therapies, these medications are non-invasive, have few side effects, and don’t tinker around the edges. GLP-1 receptor agonists offer substantial weight loss with the next generation of these drugs, retatrutide, showing up to 25% loss in body mass during scientific trials. For many who have struggled with conventional weight management strategies, these medications offer an effective tool that demands less conscious effort in terms of dietary planning and anxiety.

While these revolutionary weight-loss medications are relatively safe to use, they come with a catch. Rapid and substantial weight loss, regardless of method, leads to a reduction in lean body mass. This isn’t just about losing fat; it causes a notable depletion of muscle. When our bodies seek fuel during a caloric deficit, they aren’t discerning, breaking down both fat and muscle tissue.

So, why should we care about preserving muscle mass if we’re not elite athletes or fitness models? Muscle is absolutely critical for physical resilience, enabling us to independently navigate daily life with ease, while protecting us from succumbing to disease. It plays a vital role in maintaining a stable metabolic rate, influencing how efficiently our bodies use fuel and stabilise blood sugar. For older individuals, muscle mass is a key predictor of all-cause mortality. That is, death due to any reason. Research consistently links greater muscle mass to increased longevity.

Furthermore, muscle mass is increasingly associated with improved survival in the face of serious diseases like cancer. While muscle atrophy has long been a focus for researchers (such as myself), it was typically studied at the extremes; in athletes aiming for peak performance, or in severely ill patients suffering muscle wasting due to conditions like sepsis, AIDS, cancer, or prolonged immobilisation.

However, the pharmaceutical industry isn’t simply betting on GLP-1 receptor agonists for weight reduction; there’s a parallel, equal focus on developing drugs to safely preserve or even increase muscle mass. Beyond traditional anabolic steroids, with their well-documented and often severe health impacts, entirely new classes of muscle-enhancing compounds are entering the scene.

Firstly, we have Selective Androgen Receptor Modulators (SARMs). These compounds work by selectively binding to anabolic (muscle-building) receptors in muscle cells, mimicking some of testosterone’s effects – but, importantly, they interact less with androgenic (masculinising) receptors found in other tissues. While their muscle-building effect might be less potent than full-blown steroids, SARMs generally come with a more favourable side-effect profile and are often administered orally or transdermally (through the skin), making them considerably easier to use.

Secondly, there are next-generation treatments that specifically target the internal molecular mechanisms that put the brakes on muscle growth. Within our muscles, there are regulating proteins called Myostatin and Activin A. Think of these like a household thermostat, constantly monitoring muscle levels and applying the brakes to growth unless there’s a specific stimulus, such as exercise or hormonal signals. New drugs that inhibit these proteins are showing promising results.

A paper released this year showed that these inhibitors, when administered to non-human primates and mice in combination with semaglutide (the drug found in Ozempic and Wegovy), caused not only loss of a significant amount of body mass but to end up with more muscle mass than they had before the treatment began. This hints at a future where we might not just manage weight, but precisely sculpt body composition, with pharmacological precision.

What role does physical activity play in this evolving landscape? One hopeful possibility is a profound shift in perspective. Liberated from its primary association with weight loss, physical activity could be re-evaluated as something non-transactional – an intrinsic source of joy through movement. Physical activity could be embraced for its ability to foster community, whether through team sports, group classes, or shared adventure experiences. It could be engaged in for the simple pleasure of moving through space – experiencing the elements outdoors, finding rhythm in dance, or building the endurance to conquer a mountain trail. Ultimately, physical activity serves as a profound form of self-expression, an outlet for creativity, and how we connect our bodies with the world and people around us.

However, there’s also a dystopian vision and it demands careful consideration within the discourse. The perceived ease and effectiveness of drug-induced weight and body composition could result in overlooking physical activity’s benefits. There is a risk that a societal view emerges where pharmaceuticals are seen as the “silver bullet” to improve health, which could diminish the perceived importance of promoting active lifestyles. Additionally, with an overburdened healthcare system, these medications could be the low-hanging fruit for time-strapped GPs.

This concern of policy changes is not merely a theoretical slippery slope. The UK government is already trialling the impact of weight-loss drugs on people’s economic value. While studying lifestyle interventions from an economic and sociological perspective is valuable, we should remain skeptical of political policies. The focus of pharmaceutical products as first-line health interventions could come at the expense of supporting activities, developing spaces for activities, and providing leisure facilities.

A healthy society will always benefit from a population encouraged to be physically active. Not just to manage weight, but for the countless benefits that extend beyond body shape. The inherent value of movement, for mental health, cognitive function, social cohesion and pure human flourishing, must never be compromised for individual pharmacological approaches to health.

Ultimately, the evolving landscape presents both a challenge and an opportunity to change the discourse. It’s an opportunity to strip away decades of baggage that have burdened physical activity with being just a weight management tool. We can reclaim physical activity for what it is: a fundamental human need, a source of enjoyment, a builder of biological resilience, and a vital component of a rich, full life.

It’s time to champion and invest in environments and cultures that encourage active living for its intrinsic rewards, ensuring that even as medicine advances, the profound and multifaceted benefits of physical activity remain a central pillar of our wellbeing.