There’s something hidden on your plate – maybe it’s the chicken fried in peanut oil, or a touch of dried shrimp added for extra depth in the sauce. For most people, it’s nothing to think twice about. For me, it’s a microscopic sniper waiting to strike.

I’m part of the 30–40% of the global population affected by one or more allergic conditions, but I drew the short end of the stick. I have lived with anaphylactic allergies to peanuts and shellfish since I was old enough to speak. Allergic reactions can range from mild irritation like hives or a rash, to life-threatening emergencies. Mine sit at the severe end of the spectrum, where even trace exposure can provoke a life-threatening immune response.

Even with the widespread prevalence of allergies, misconceptions persist. Despite having an extensive pool of information at our fingertips, we still need to learn how to distinguish fact from fiction. Growing up with allergies, I was always on the lookout for how to solve them, wondering how allergy treatments work. But before I could explore that, I needed to understand how it happens in the first place.

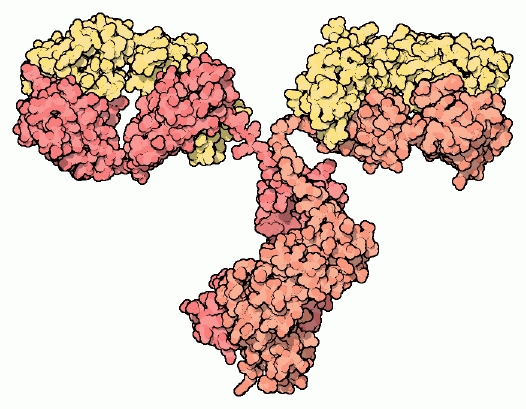

When you have an allergy, your immune system mistakenly identifies a harmless substance – such as pollen, pet dander, or certain foods – as a threat, and produces immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies against it. Upon re-exposure, these IgE antibodies trigger mast cells, a type of white blood cell, to release chemicals like histamine, which leads to symptoms such as itching, swelling, sneezing, or even life-threatening anaphylaxis. Normally, IgE would identify a harmful trigger to the body such as a parasite. In a regular immune system response, mast cells help protect your body against diseases. And, in an actual infection, the symptoms would help you fight against the problem or tell you that something is wrong. In the case of allergies, the immune system isn’t being helpful – it is overreacting to something harmless.

Although we understand how allergies develop, there is still no definitive way to eliminate them completely. One major obstacle in developing an effective treatment is an inadequate understanding of what precisely occurs during an allergic reaction. Blood tests can identify whether a person has IgE antibodies linked to a particular allergen, but they do not reveal the exact subtype or the specific components within the allergen that trigger the immune response. If someone is allergic to dogs, the test might show the presence of dog-specific IgE, indicating a reaction to dogs in general. However, it cannot pinpoint which specific particles in dog dander or saliva are responsible for the allergic reaction.

If researchers could determine the exact molecular targets that IgE antibodies bind to, they could develop more personalised treatments that address those interactions directly and help prevent allergic reactions. In laboratory settings, scientists use a technique called flow cytometry to label allergens, such as peanut proteins, with fluorescent markers. This process involves suspending cells from a blood sample in a fluid and passing them through a detector that identifies how IgE interacts with the allergen. Although this method provides precise information, it remains too complex and time-consuming to be used routinely in clinical practice.

Another reason is a lack of treatment options. Because allergic responses vary widely from person to person, it is challenging to develop a universal allergy treatment, a one-size-fits-all solution. While mild cases may be managed with over-the-counter antihistamines, others require more specialised care.

To be diagnosed with an allergy, the level of allergen-specific IgE in the blood typically needs to reach at least 0.7 IU/ml. In some cases, a person with allergies can have IgE levels of up to 4,000 IU/ml, highlighting just how different these responses can be. A treatment that works well for someone with mild seasonal symptoms might be ineffective for someone with a much stronger reaction, and vice versa.

Trying out alternatives

One treatment I tried a few times was oral immunotherapy (OIT), a medical treatment designed to help desensitize individuals with food allergies by gradually introducing small, controlled amounts of the allergen to build tolerance over time. To ensure my safety, I was required to stay in the hospital for observation during treatments in case of an allergic reaction. Fortunately, as a result of OIT, I can now eat mussels, oysters, and scallops. However, when given the first dose for shrimp allergy testing, I immediately had an allergic reaction; while OIT can show promising results, it may not be effective for everyone.

It is no wonder with the limited solutions available that parents of children with allergies and those with allergies themselves would turn to ‘alternative’ solutions – my mother being one of the many worried parents trying to seek a solution for her child’s allergies. In our situation, it seemed very promising to hear of friends being cured of their food allergies or eczema after attending a few treatment sessions. One such treatment was NAMBUDRIPAD Allergy Elimination Techniques (NAET) – which claims to be a:

“non-invasive, drug-free, natural solution to alleviate allergies of all types and intensities using a blend of selective energy balancing, testing and treatment procedures from acupuncture/ acupressure, allopathy, chiropractic, nutritional, and kinesiological disciplines of medicine”.

When I was in my teens, my mom and I decided to explore what NAET had to offer, encouraged by the promise of alleviating allergies with minimal risks. I was told to hold a glass vial of liquid, which the NAET practitioner explained to me contained the essence of the allergen, while the strength of my muscles in my opposite arm was tested. The practitioner explicitly told me to hold the glass part of the vial – if I held the cap it would not work. She then applied light pressure to my arm out in front of me and stated that if I was allergic, my muscles would be weaker, causing my arm to drop. But if I was not allergic, my arm would remain strong, withstanding the push.

What the practitioner did not know was that hidden in my hand, I held the vial by the cap, with no contact to the glass. Although it may have been a waste of money and time, the skeptic in me refused to follow the treatment blindly. Despite my hand not being in contact with the glass, it seemed the practitioner continued to find allergies to some of the allergens she was testing, contrary to her previous statement.

What I later came to learn is that this technique is also known as Applied Kinesiology Testing, a pseudoscience practice that is “not more useful than random guessing.”

Bioresonance therapy

Continuing my hunt for more allergy treatments, I went to try a bio energetical treatment called BICOM Bioresonance therapy (BRT). BRT is an alternative treatment to alleviate allergies and chronic conditions by manipulating the body’s electromagnetic vibrations.

The treatment is based on the belief that all living cells emit specific frequencies and that imbalances or “disharmonious” vibrations – caused by allergens, toxins, or illness – disrupt the body’s function. It involves extracting the patient’s electromagnetic signals through electrodes, processing them via the BICOM device to “invert” or neutralise pathological frequencies, and then transmitting the adjusted signals back into the body. This is said to weaken harmful vibrations and strengthen healthy ones, restoring balance and improving overall physiological function.

Similar to NAET, the procedures at BRT were non-invasive and did not pose much risk. Upon speaking with Mr Vincent Ho, naturopath and principal therapist at BRT, I could tell he was dedicated to his work to help people. During my treatment, it was clear to me that many people felt safe in his care. He had shared with me countless testimonials from patients who reported being cured of their issues, supported by many promising images of patients with eczema before and after their treatment. One of the success stories was a little girl from Dubai, who was brought all the way to Singapore with her family just for her treatment.

The BRT website is full of such testimonials… as well as articles refuting the claims of their critics, including an article from Straits Times. Straits Times claimed that “advocates may trot out testimonials from satisfied customers, but testimonials are not data” – to which BRT responded with testimonials from their “many satisfied patients”:

“If BRT paid me money to tell you the effectiveness of Bioresonance Therapy, then it is an advertisement. But, if I am the one that paid BRT money for my treatments and I tell you the effectiveness of Bioresonance Therapy, then it is called testimonial.”

BRT contends that testimonials are valuable because they are earned through a positive patient experience and not a sponsored presentation of the treatment.

In search for more information on BICOM Bioresonance, I went to their official website in search of clinical studies done to assess the performance of the treatment. What I found was a study expressing that the BICOM optima device for Bioresonance-therapy showed significant improvement in symptoms and quality of life for patients with allergic rhino-conjunctivitis. However, it is important to note that there is a lack of a control group in the study, and the authors themselves admit that it cannot be distinguished whether symptom improvements were due to the treatment, placebo effect, natural recovery, or seasonal allergy variation, stating:

“With the design of this study, namely single-arm with an intraindividual comparison of symptoms before and after therapy, it cannot be excluded that there are other causes for the improvement… such as the natural course of the disease… or placebo effect.” (Section 8.4)

The study relied on patient’s self-reported weekly symptom scores as the primary measure of success – without any objective physiological markers to back them up. Furthermore, the researchers chose to simplify data collection by avoiding daily symptom diaries, claiming that:

“Simplifications were made… As a result, the results are more ‘blurred’ compared to a dedicated patient diary.” (Section 7.6.7)

In such an unblinded study, this opens the door to expectation bias, given that participants know they’re receiving treatment.

I was searching for clear answers; I was met with ambiguous ones. I contacted with Associate Professor Elizabeth Tham, Senior Consultant and Head, Division of Allergy, Immunology & Rheumatology, Department of Paediatrics, National University Hospital. She explained:

“Unfortunately, [these treatments] are all unproven – they either do not target the IgE-mediated pathway, which is how allergies come about in the first place, or they just don’t have any scientific evidence that they work.”

If it worked, it wouldn’t be alternative?

There is no sound evidence to prove that treatments like NAET and BRT work. It is possible that there are ‘alternative’ treatments that do work, but we do not yet have good evidence to think so. As for the positive testimonials, part of the apparent effect of such treatments is the kind practitioners who are genuinely concerned for your wellbeing. When the risk of harm is low, like when dealing with reducing pain tolerance, this approach might be helpful – but, when it comes to cases such as life-threatening allergies, we need to be careful.

As Prof. Tham explains, the problem with patients receiving inaccurate information is not only a waste of money and resources, but also the risk of a serious allergic reaction if the treatment claims that they can eat the allergen. It is safer to stick to mainstream, scientifically proven therapy.

Although it may seem hopeless in the field of allergy treatments available, there may be light at the end of the tunnel. Recently, the FDA approved Xolair (omalizumab), an injection to help treat IgE-mediated food allergy. By binding to IgE, Xolair blocks IgE from binding to its receptors, reducing the risk of allergic reactions after accidental exposure including anaphylaxis. Prof. Tham explained that the use of omalizumab together with OIT is currently undergoing researched, with the aim of allowing patients to move up to dosages safer than OIT alone, bringing science another step closer to addressing allergies.

In the case of less-serious ailment, it may seem more acceptable to try these ‘alternative’ treatments since it does not pose direct harm to the patient. However, it is more than the dangers of an allergic reaction that we need to take note of – it’s also the dangers in the way we think. When assessing any information, it is helpful to be equipped with a skeptic’s toolbox to help us fact-check.

A skeptical toolbox

First, we must be careful to spot when logical fallacies are committed in any reasonings made. One common example is the anecdotal fallacy, where personal stories are taken as proof of effectiveness. While these testimonials may be emotionally persuasive, they are uncontrolled, biased, and often ignore other contributing factors.

Another frequent misstep is the post-hoc fallacy — assuming that just because something happened after treatment, it must have been caused by it. For instance, someone might claim, “I went for NAET treatment and now I’m no longer allergic, so NAET cured me.” Without considering natural improvement over time, placebo effects, or unrelated lifestyle changes, this statement implies a causal relationship when there is only temporal succession. For example, it is wrong to assume that a rooster’s crowing causes the sun to rise, simply because the crowing precedes the sunrise.

Then, there is confirmation bias, where only supporting evidence is acknowledged while contradictory research is ignored. It is not uncommon to see positive testimonials for unproven therapy promoted widely, while systematic reviews showing no measurable effect are left out of the conversation entirely.

In addition, we should learn to ask questions. For example, if the treatment works so well, why has it not been adopted by mainstream allergists? Or, is the claim assuming causation when it might only be correlation?

We must remember that our confidence in what we think we know can sometimes cloud our judgment. Being open to new ideas is important, but so is staying grounded in evidence. In a world where misinformation spreads quickly and often carries emotional appeal, developing critical thinking isn’t merely helpful — it’s a form of protection. A skeptical mindset guards us not against curiosity or openness, but against false confidence disguised as certainty.