When we browse the news of the day, because we see mostly the same collection of stories repeated across most of the newspapers on the market, it’s easy to get the impression that the stories we read are a comprehensive account of what has happened – this is the list of important things that have happened, if it’s on the list, it’s because it happened; if it’s not on the list, it’s because it didn’t happen, or it wasn’t important enough to make it onto the list.

However, this is not necessarily the case: for a surprisingly high percentage of stories that make it into the mainstream media, the reason they’re reported in multiple titles is simply that each of those newspapers draws from the same source. Perhaps they all received the same press release, were invited to the same press conference, or maybe pulled the story from the same newswire. One Press Association article can be the basis of reporting across a dozen newspapers, television broadcasts and radio bulletins, with the same facts proliferating across the media landscape. In the best-case scenario, those core facts were correct in the original Press Association article; in the worst-case scenario, a media industry starved of time and resources can inadvertently scatter falsehoods, gilding them with the credibility of a trusted masthead.

And that’s only considering the stories in which each piece of ‘original’ reporting plucked the same press release from the wire – it doesn’t consider the effect of secondary reporting. When the Mail Online sees a story getting a lot of traction on one of their competitors’ sites, they routinely grab that story, reword it a little, and publish it to their own site as their own. Now the same piece of reporting is published to another mainstream platform. Radio and TV news producers are just as resource-starved and in need of content, so they, too, will look to the newspapers for potential stories for the day’s bulletins – so that one piece of reporting is now being broadcast across multiple formats, on an hourly or half-hourly schedule.

Radio current affairs programs and morning shows and call-in shows and TV talking heads shows, similarly, are always keen to cover the day’s big news, so they will also look to the newspapers or the newswire their news for the day. Add in rolling 24 hour news channels and the voracious appetite of digital readers on social media aggregators, in effect, without any hint of intentional collaboration, the media becomes a machine for amplifying reporting, and the same handful of sources bounce around this media ecosystem, repeating from one platform after another, building the impression that this is what The News is today. It begins to resemble a kind of pseudo-consensus, compiled at pace and with convenience in mind.

Having the need for pace and convenience baked into the structure of this pseudo-consensus makes it somewhat vulnerable – it’s why PR companies and crisis management companies and other agents of spin make their living exerting their influence at the earliest stages of a story’s life, knowing that any soundbites or finessing of the narrative present in the newswire or press release will be more likely to get picked up by each stage of this amplification engine, and proliferated across the media landscape. That proliferation means the spin becomes part of the official record, gaining an inflated influence on members of the public, because people naturally assume that if they’re hearing the same thing from so many different places, there must be something to it. If it was just in the local paper, I might take it with a pinch of salt, but I also saw it in the Mail and in the Star and in the iPaper and Alexa read it out as a headline to me and it appeared in my Google News feed and a few of my friends shared it on Facebook and I heard the local radio drivetime show do a phone in about it, so it must be true. It is churnalism, but it starts to resemble consensus.

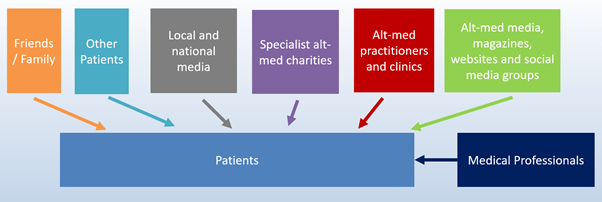

The effect of this kind of repetition can have a significant effect in the real world, never more so than when it comes to patients encountering health misinformation, and the impact it can have on the decisions they make. Patients are influenced by lots of different sources – their medical professionals being one of those sources, but other sources include the people in their life, their friends, their family, and even other patients they might meet either in person or online, in support groups, if their health issue is particularly serious or particularly hard to diagnose and treat.

There are also the organisations the patients might encounter, such as patient support groups, patient advocacy groups, or even specialist charities who focus on that particular condition. These organisations may aim to spread nothing but evidence-based information, but they still could knowingly or unknowingly become vectors of misinformation. There’s even, still, officially recognised registered charities who specifically exist in order to spread health misinformation – such as, in the case of cancer patients, charities like CancerActive and Yes To Life, who routinely promote to cancer patients alternative medicine and (ineffective) alternative modes of cancer treatment.

Among the other factors influencing patients are the alt-med practitioners and the clinics themselves – even with a subject like cancer, which in the UK there are laws against claiming you can treat or cure, it’s easy to find claims that range from helping cope with the effects of cancer treatment, to augmenting cancer treatment in a complementary way, to helping your body fight cancer, to outright cancer cure claims. Back in 2017, I witnessed Gerson practitioner Patrick Vickers directly and specifically tell cancer patients to stop taking their cancer medication. Vickers is far from the only confident practitioner offering dangerous advice and instruction, and doing so with such force and conviction that it’s no surprise some patients believe him, especially when the alternative is the percentage survival rate offered by a doctor.

Besides the organisations and practitioners, there’s the local and national media – the Daily Mail has long since been on a quest to separate every noun in the known universe into “causes cancer” or “cures cancer”, and there’s barely a day that goes by that the Daily Express doesn’t tell you what 59p wonder herb will prevent cancer or heart disease, or which common ingredient will hugely increase your risk of dying tomorrow. These stories have a cumulative effect, even if each individual story doesn’t seem like it makes an impact. Equally, so do the stories that used to fill the local newspapers about cancer patients, when given a terminal diagnosis, fundraising in order to pay for a miracle cure abroad. Thankfully, those stories are a lot less common than they used to be, partly due to an investigation I published in 2018 in the BMJ, but they still pop up from time to time, and they’re almost all still available online to be picked up and shared around anew.

And then, on top of all of that, there’s this ecosystem of alternative medicine media – the magazine that promotes this week’s miracle cure, the health and wellness podcast that interviews whoever is going to claim to have a 99% cure rate this week, the blogs and social media groups and Instagram pages and YouTube channels who exist to disseminate viewpoints that differ from the medical consensus, at an amplitude, frequency and certainty of delivery that an evidence-based position could almost certainly never compete with.

All of those different voices and channels have an influence, and of them, the medical professionals are obviously completely outnumbered – the vast majority of people that most patients talk to about cancer and the vast majority of people they hear from are likely to not be medical experts. Misinformation can creep in from any one of those sources, and when many of those alternative voices align around the same messaging – maybe that Big Pharma wants to keep you ill, or that a toxin-free body doesn’t develop cancer or that cancer cells can’t survive in an alkaline body or that cancer can be cured by cannabis oil or supplements or smoothies or black salve or chelation or the next thing or the next thing – that alignment of messaging can start to resemble consensus. “Of all the people I’m hearing from, they almost all agree that the doctors are wrong. Why would so many of them think that, if there wasn’t something in it?”

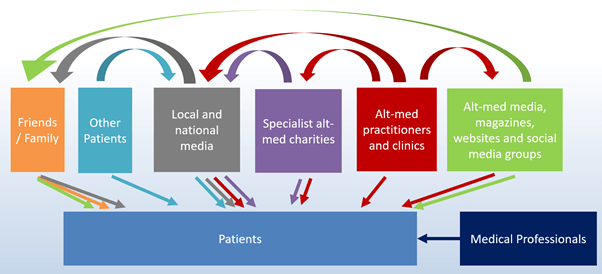

Sadly, the situation is even worse than that, because despite how it might seem from the centre of that maelstrom of inputs, these different channels of misinformation aren’t independent, they’re echoes of each other, drawing the same misinformation from the same sources. Our hypothetical patient might encounter cancer misinformation from their friends or their family, or from other patients, but where did those people get that information? From each of the other channels – other patients, other friends, the media, and those specialists alternative medicine charities, magazines, blogs, social media accounts and flashy, active ecosystem.

And what about the media, where do they get their stories? Often, they’re stories about patients who are sure their alternative medicine journey will cure them – because patients who were on the receiving end of that maelstrom of misinformation turn into vectors themselves, providing the case studies, testimonials, inspirational lifestyle stories and news articles that go on to echo their way back to our hypothetical patient.

When it’s not the patients who are talking to the media, it’s the clinics, the practitioners, the evangelists and believers, who want to spread the word about their miracle cures – maybe they’re talking to their local newspaper about their successful local clinic, or maybe they’re appearing on podcasts and YouTube channels to tell the credulous host how many cancer patients they’ve helped and exactly how their miracle cure works. Or maybe they’re talking to those specialist cancer charities, who package up their stories in articles and presentions to other patients, or wrap them up with some neat PR and present them to the media, who pass them along to the patients

In effect, it’s possible for the same handful of stories to echo their way back to our hypothetical patient from all sides, and it can start to feel like that consensus that we value so highly.

This is why it’s so important that when we try to push back against misinformation and pseudoscience, we think about the various channels that spread and amplify it, and what we can do to tackle each one of those channels, to lessen the impact of the echo chamber.

It is also why it simply isn’t enough to rely on a “marketplace of ideas” approach to misinformation, because what determines whether an idea is accepted isn’t how right the idea is, but how seductive it is, and whether it can spread from person to person before it harms its original host.

A false claim about a fake miracle cure can get around the world before the evidence has had time to put it’s boots on, and once that false claim starts pinging around this misinformation echo chamber, it can be enormously difficult to halt its momentum.