If you ever want to strike fear and inspire outrage in the hearts and minds of the right-wing media and their audience, all it takes is three words: “I identify as…”. It’s like a Bat-Signal summoning a cacophony of caped culture war crusaders, echo-chamber-locating every tiny morsel of perceived ‘wokeness’ they can gorge upon to help spread their misinformation guano.

Those three terrifying words are of course most associated with the ongoing battle for trans rights, so it’s perhaps not surprising that those who are against such things are particularly keen on grasping at examples of identification that fall outside of gender as it helps both their slippery slope argument and the reinforcement of their favourite ‘joke’.

Imagine therefore the number of whispers that must have been passed to prompt what appears to be some classic FOIA request-fuelled muck raking by the tabloids to dredge up the recent story of a school in Scotland that allegedly “allows a pupil to identify as a wolf”.

The story seems to have been copy/pasted across all of the usual suspects: The Daily Mail, The Sun, The Daily Record, GB News, and The Telegraph to name but a few. With the rabble well and truly roused the disbelief and anger reverberated around social media. TalkTV even used it as an excuse to criticize the new Labour government (please don’t lycan-subscribe).

I’m somewhat embarrassed to say that I came across this story because it was shared on Facebook by a friend of mine who should know better (and has been informed of such). Even at first glance it looked questionable – after all, it hasn’t been too long since fact-averse podcaster Joe Rogan kicked off baseless rumours about litter boxes in schools for pupils who identify as cats and was subsequently chastised from all directions, even including the immune-to-irony writers at the Daily Mail. With suspicions of sensationalism, I posted a message about the wolf story on the Glasgow Skeptics Facebook page asking if it seemed questionable. The general consensus in the comments was yes, but this was just the beginning. A few days later an email arrived in the Glasgow Skeptics inbox from a member of staff at the school in question. They had spotted my Facebook post and felt compelled to make contact.

According to them, the real story is “neither as interesting nor as dramatic as those headlines would suggest”. Unfortunately, it is considerably more depressing and tells an age-old story that we really shouldn’t still be dealing with in these supposedly enlightened times.

In Scotland, as part of the transition from primary to secondary school (ages 11-12) there are handover discussions from representatives of one school to the other. During a very busy meeting there was a passing remark of one child who “identifies as a wolf”, but there was no time for elaboration and mental notes were made to deal with that situation if and when it arose. Many weeks passed in the new school term without any sign of wolf-like behaviour from the pupil in question, but eventually they confided in a member of staff that the bullies who had tormented them in primary school were keeping the momentum going in secondary school.

If you are a young person experiencing bullying, guidance and support can be found in various places such as Kidscape, the Anti-Bullying Alliance, and the National Bullying Helpline. Please seek help if you need it.

The child is something of a loner, perhaps finding it hard to make friends, which makes them an easy and obvious target for the less pleasant proportion of the playground population. Upon enquiry about the wolf persona, the child struggled somewhat to explain it, but essentially it appears to be some form of disassociation, protection, and perhaps even escapism of sorts.

It’s heartbreaking enough that this is happening, but to have their story paraded across the tabloids and social media for the real baying mob to howl about will surely cause even more hurt, and could even spark an increase in the bullying that possibly led to the creation of this persona in the first place. As for that persona, according to my source “The child has never, in secondary school, exhibited any sort of animal behaviour. Never expressed identity as, affiliation with, behaviour of any animal.”

So, to be clear: The bullied child wears school uniform and not a pelt. The bullied child does not disrupt classes with ear-shattering howls. The bullied child has never bitten any of the other pupils. The bullied child uses the bathroom as normal and does not request to defecate in nearby forests. The bullied child has never urinated near their desk to establish territory. The bullied child has not demanded that the school canteen caters for dietary requirements such as moose, elk, or bison. The bullied child has never made the excuse “Sorry, I ate my homework”.

The bullied child’s wolf ‘persona’ has not had any impact on the ability of other pupils to get on with learning, nor has it required any form of special accommodations from staff. All of the images popping into the heads of those who read any of the articles, and all the snarky comments and fury on social media that it generated, were based on fiction. The real problem here is bullying, and not an unconventional child’s desire to find some form of escapism to help deal with it.

The one thing that the papers did get right is that there is indeed no such condition as ‘Species Dysphoria’. It certainly doesn’t appear in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), although there has been some limited scholarly discussion around the topic using the term ‘Species Identity Disorder’. It’s unclear whether the council involved actually used that term, or whether it has been fabricated by the storytellers. Even if it was the former, it can easily be attributed to a somewhat clumsy but genuine attempt to explain the child (allegedly) being a furry.

Either way, it facilitates an interesting bait and switch in the articles as the headlines start out with “identify as”, then subtly move to “identify with” a few paragraphs down. There’s much misunderstanding about the furry community (you can find an excellent mythbusting article here), and in the vast majority of cases it’s a harmless hobby that facilitates escapism, creativity and self-expression. Despite that, it’s still deemed a danger by the anti-woke brigade. This is possibly because there is a statistical skew away from heterosexuality and gender norms, so the story has an overpowering stench of a sideswipe at the trans community. It’s also notable that furries have an above average percentage of neurodivergence in their community, and it’s thought that being able to create a persona that is very different from your day-to-day one may be helpful in helping you cope with social difficulties, or at least temporarily escape from them.

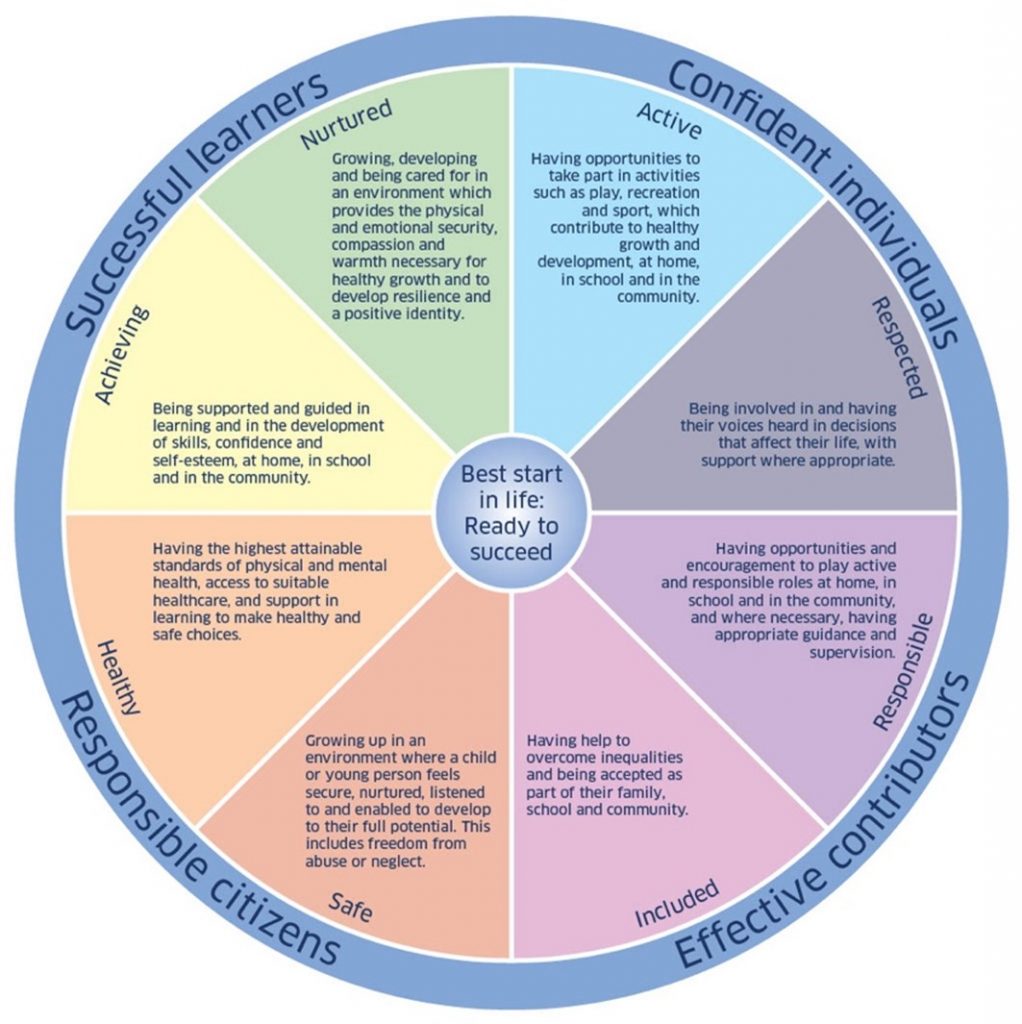

So, despite the fact that the school in question has not had to make any accommodations for the child’s wolf persona, even if they had it might not necessarily have been a bad thing. The initiative that’s taking a beating for those non-existent accommodations is the Scottish Government’s Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) policy. There’s nothing in there that suggests taking over-the-top measures to incorporate every aspect of every child’s identity, but it’s clearly aware of the diversity of personalities, ideals, problems and passions across a school’s population, and the need to support them all as best as possible during a crucial time in their development.

There’s certainly no mention of Species Dysphoria and how to deal with it. Even the evidently positive Wellbeing Wheel is displayed with the accusation that it’s being used as a vehicle to usher in some kind of ‘woke agenda’.

The Daily Mail unsurprisingly tries to strike an additional blow below the belt as their article concludes with an elongated commentary from Christopher McGovern of the Campaign for Real Education (CRE), and former adviser to the Policy Unit at 10 Downing Street. McGovern uses the story as a springboard to dive into a tirade about “the ‘woke’, politically correct, victimhood industry that currently defines too much schooling”, with a blissful lack of awareness that he’s ranting about something that simply isn’t happening. Perhaps the organisation he represents should consider advocating for digital literacy, fact-checking, and critical thinking on the curriculum. The CRE advocates for a return to a more authoritarian method of teaching, and McGovern’s anti-woke soundbites and opinion pieces seem to pop up in the media with monotonous regularity.

So, now that we’ve unmasked the real villain, very much like an episode of Scooby Doo, we find the culprit to be much more mundane than we were initially led to believe. There are lessons to learn for all parties:

To the casual reader: please be careful when reading ‘news’, as there’s almost always more going on than will ever be reported. Consider what you’re not being told, what the real harm is, and who the actual antagonists are in the story. Don’t eat what they’re feeding you without at least giving it a sniff!

To the news outlets reporting on this, and other similar stories: you can do much better, but I think you know that already.

To the bullies: you will, with great certainty, regret your current behaviour. Get hooked on kindness instead. The dopamine hit is much better, and it’s infectious. There’s even science to back it up! Make amends if you can.

To the young person at the heart of this story, or anyone else in a similar situation: this is not an easy road you’re on, but things get better. Your tormentors will invariably grow tired or grow up. You’re at the perfect age to discover who you are and who you want to be, so go explore and express yourself. You will find your tribe, or will be just fine as a lone wolf if that’s what you want. You do you!