The biggest irony of the repeal of Roe v Wade that has caused the recriminalisation of abortion in some southern states of the USA is that even the most fervent of anti-abortionists have almost entirely ignored a widely used contraceptive method that has aborted far more of the ‘unborn Beethovens and Einsteins’ so prominent in anti-abortion discourse than all the world’s abortion clinics combined. These millions of abortions were caused by one of the ways in which intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUDs) work and, for different but related reasons, both anti-abortionists and family planners seem to have agreed never to mention it. I believe it is worth publicising, however, because it may help to restore the status quo in the USA that prevailed for nearly half a century. It may also help to quash efforts to restrict abortion rights in Europe.

Whatever Constitutionalist arguments were invoked by religious and/or Trump-appointed supreme court members to justify it, the Roe v Wade repeal is a triumph of misogyny which, as well as rape victims, will disproportionately affect the people whose lives are most at risk of being blighted by unwanted pregnancy – teenagers, often from poor families, forced into early and single motherhood or early marriage with all the well-documented problems that generates for them and their children; and mothers already stretched by caring for their existing children. Middle-class women will, as usual, navigate the obstacles more easily, even if they have to go interstate or abroad. Delaying motherhood will increase their education and employment prospects, further increasing their life-chances compared with their poorer counterparts.

If anyone wants to set up a Museum of Irony and Paradox, the main exhibit could focus on abortion, because it attracts so much of the stuff. There’s the capital punishment paradox – the fact that among typical ‘pro-life’ anti-abortionists, with their traditional set of moralities, are many enthusiasts for capital punishment. There’s the historical paradox that we get lectured on the sanctity of life by the spiritual heirs of Catholic and Protestant heretic-burners, to mention only the Christian kind.

There’s also the irony that a large proportion of human pregnancies end in very early spontaneous abortion (the term ‘miscarriage’ usually describes spontaneous abortion later in pregnancy), which suggests that the putative deity of the fundamentalists isn’t interested in maximising foetal survival. Indeed, since many of these early spontaneous abortions seem to involve anatomical or chromosomal abnormalities that would lead to severe birth defects if the pregnancy were to go to term, it also suggests that God is a Foetal Darwinist.

Finally, there’s the peculiarly American irony that the Southern states and white fundamentalists, who have only recently and reluctantly got over their enthusiasm for church-sanctioned slavery and segregation (as Tom Lehrer called it, ‘The land of the boll-weevil/Where the laws are mediaeval’) are among those most keen to ban abortion. This would have the biggest impact on the disproportionately African American poor.

For me, though, the chief irony has always been the way in which anti-abortionists reveal their fundamental dishonesty and hypocrisy over the millions of very tiny ‘unborn babies’ (aka ‘potential Beethovens’) who are, to use their terms, ‘murdered’ every year by the action of contraceptives, especially but not exclusively the intrauterine device (IUD) or ‘coil’. Ever since IUDs were introduced in the 1960s, it was obvious that they worked in a number of ways, including the destruction of tiny Beethovens (they might, of course, be tiny Hitlers or Stalins) during the first few days after fertilisation (and thus ‘personhood’), before or after the implantation of the blastocyst – the embryo’s initial and tiniest manifestation. They are therefore at least part-time abortifacients (ie drugs or devices that cause abortion) and they remain abortifacients even if most of the time, they prevent pregnancies by killing or disabling sperm and/or ova before they can unite.

The fact that the tiny, brainless Beethovens who are aborted at this stage are barely visible to the naked eye does not prevent the Vatican from asserting that they are large enough to accommodate a soul, though that evidence-free assertion dates, along with the doctrine of papal infallibility, only from 1869. Previously, Rome held, equally without evidence, that ‘ensoulment’ took place later, at 40 days for a male foetus and 80 days for a female (and presumably at 60 days for the occasional true ‘hermaphrodite’). Islam gives us a ball-park range of 42-120 days for both sexes: take your pick.

Until the 1830s in Britain, inducing an abortion was not an offence under common law unless it took place after ‘quickening’ – ie obvious foetal movement – around 18-20 weeks’ gestation. Even after seven weeks of development and perhaps two missed periods, our little Beethoven/Hitler is barely 3/4 inch, or 18mm, long. In Oklahoma a few years ago, legislators seized on a more modern version of the Beethoven argument. It was proposed, and very nearly enacted, that women seeking abortion, even after rape, had to watch and listen while a doctor did an ultrasound examination of the foetus and described its cute little fingers. According to The Guardian:

The sponsor of that law, the Republican state senator Todd Lamb, said it was intended to give the mother “as much information as possible about that baby” because it might grow up to win the Nobel prize.

I wrote to Sen. Lamb, making some of the points that I’m about to describe but like many anti-abortion British politicians, he did not respond to my arguments.

Today, there are two types of IUD. The simpler kind is a T-shaped bit of plastic, wrapped around with copper wire. The combination of mechanical and inflammatory action from a foreign body barging around in the uterus and the local toxic effect of copper makes things difficult for sperm and fertilised or unfertilised ova. In the other sort, sometimes called an intrauterine system, the device is impregnated with hormones that may reduce (but are not guaranteed to prevent) ovulation, or implantation.

However, for both types, the product information sheets concede (though usually not very prominently) that causing early abortion is among the modes of action and that people with strong views on these matters may prefer to use other methods. As a 2002 review in a leading obstetric journal concluded,

although prefertilization effects are more prominent for the copper IUD, both prefertilization and postfertilization mechanisms of action contribute significantly to the effectiveness of all types of intrauterine devices.

They also apply to some types of oral contraceptive but I will leave those out of the argument.

Let’s look at what ‘postfertilization mechanisms of action’ means, using the pro-life language of ‘murdered babies’. There are currently over 150 million IUD-users world-wide. Apart from the 100 million of them who live in China and are thus mostly beyond the reach of anti-abortionists inspired by Abrahamic religions (the only ones that seem to bother about it much), that means 50 million women, each of whom might be murdering at least one soul-equipped baby every year, even if hormone-impregnated IUDs mean that they only release three or four ova in that time. That could mean 50 million induced abortions a year, which is far more than the total combined annual live births of Europe and the USA, let alone the much smaller total of notified legal abortions. Even if the true figure for IUDs is only a tenth of that, 5 million is still an awful lot of minced-up micro-Beethovens, though far fewer than are lost in the daily Malthusian wastage and Darwinian weeding-out of defective embryos.

The essence of anti-abortionism is that destroying a tiny embryo is morally the same – or virtually the same – as destroying a full-grown human baby. Anti-abortionists must maintain that stance, or their case collapses. They also have to maintain (and most of them do) that ‘humanity’ begins at fertilisation. That is why the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children campaigned vigorously but ineffectively a few years ago in Britain against increasing the availability of post-coital ‘morning after’ contraception; which works – whichever method is used – by ensuring that if a fertilised ovum results from the coitus in question, it is aborted, either by the prescribed medication or, less often, by inserting a post-coital IUD.

One leading British anti-abortionist obstetrician, Prof. Hugh McLaren did try to argue that ‘humanity’ began at implantation rather than at fertilisation, so that IUDs were acceptable as contraceptives but he encountered two unanswerable objections. The first was that if he could move the goalposts to suit his moral beliefs, so could the pro-choice tendency. The second was that IUDs could clearly work not only after fertilisation but also after implantation. Furthermore, his views were not typical of anti-abortion doctors who are also obstetricians and thus particularly well-informed about foetal development.

A survey of 1760 US obstetricians found that in a response rate of 66% (which is high for this sort of survey),

One-half of US obstetrician-gynecologists (57%) believe pregnancy begins at conception. Fewer (28%) believe it begins at implantation, and 16% are not sure. In multivariable analysis, the consideration that religion is the most important thing in one’s life…and an objection to abortion…were associated independently and inversely with believing that pregnancy begins at implantation.

In other words, the more religious and anti-abortion the obstetricians, the more likely they were to believe that pregnancy, humanity and ‘personhood’ begin at conception and that conception means fertilisation, not implantation. Accordingly, when our own abortion laws were under attack in the decade or so after the 1967 Abortion Act was passed, I wrote to several prominent British antiabortionists along the following lines.

You apparently regard the fertilisation of the ovum as the starting point of humanity. I do not share this view but it is not an entirely dishonourable one. However, you may not realise that IUDs work not only by preventing fertilisation but also by destroying the fertilised embryo during the first week or two of its existence, both before and after implantation. Most of the hundreds of thousands of British IUD-users are sexually active, so they could each be having an early abortion several times every year. This makes for an awful lot of murders of potential Beethovens (as you regularly portray abortions) and probably amounts to far more ‘murders’ than all the abortions formally notified under the provisions of the Abortion Act. If you really are as outraged by abortion as you claim, you will, of course, want to make it very clear that you are just as outraged by those who manufacture, insert or wear IUDs as you are by those involved in murder/abortion at later stages of pregnancy. I therefore invite you to make an immediate public statement to that effect. Alternatively, if you feel unable to make such a statement, I invite you to explain why you regard the destruction of a mini-Beethoven at one or two weeks as so much less worthy of your indignation than the destruction of the same mini-Beethoven a month, or two or three months, later.

Among the people I wrote to were the former Roman Catholic Archbishop of Westminster (the late Cardinal Basil Hume) and several Members of Parliament, and I still have a collection of wonderfully evasive letters from them. Most tried to change the subject. Leo Abse, one of the MPs and noted for his flamboyant and articulate style, was struck uncharacteristically dumb and declined to continue the correspondence.

I had – and later published – an extensive correspondence with Cardinal Hume, who eventually conceded that if what I said about the mode of action of the IUD was true, which it clearly is, then the point I had made was an important one. He reminded me of his church’s traditional opposition to all forms of contraception but he never subsequently referred in public to the IUD problem. Pope John Paul II (to whom I didn’t write) mentioned IUDs briefly and in passing as part of a general attack on abortion in the early 1980s but rarely referred to the matter thereafter. He never, as far as I know, singled out IUDs, despite their enormous numerical importance in any calculation of murdered Beethovens and blighted souls. I think Americans could have a lot of useful and innocent fun by similarly tormenting the US equivalents and exposing their hypocrisy.

To publicise the issue, I even devised a little stunt in the late 1970s. Together with a medical journalist and an academic expert on abortion law, I arranged for a leading professor of gynaecology to insert an IUD into the uterus of a friend of mine who was a prominent women’s magazine editor. We all then signed a letter testifying that we had witnessed this illegal procedure, namely using an instrument, (specifically an IUD) to procure a miscarriage, contrary to the Offences Against the Person Act of 1861 (where the prohibition of abortion is picturesquely sandwiched between prohibitions of bigamy and buggery) and without the two medical opinions, medical reasons and other bureaucratic requirements of the reformed 1967 abortion law. We then jointly posted this explosive document through the letter box of the Director of Public Prosecutions. Our bit of street theatre got into the papers, but produced absolutely no response. After several months and several reminders, a weary letter from the DPP informed us that he would not take any action against the gynaecologist, despite our request that he should do so. Significantly, he did not argue that the professor had not broken any law.

Short of inviting Cardinal Hume to be one of the witnesses, I couldn’t have done more to alert British anti-abortionists to the medical facts about IUDs but they have remained very reluctant to mention the matter. The reason is obvious. They know that most people – probably including most Catholics – know the difference between an acorn and an oak tree and know that destroying an acorn, or even a small sapling, is not the same as cutting down an oak tree. They know that opposition to contraception is a political dead duck, even in Catholic countries. Finally, they know that most people cannot get very worked up about the moral status of something that is almost invisible to the naked eye but they dare not say that murdering unborn babies doesn’t matter provided that they are only little ones, because that, of course, is exactly the position of the pro-choice lobby. We differ only in our definitions of ‘little’ and all such definitions are largely arbitrary.

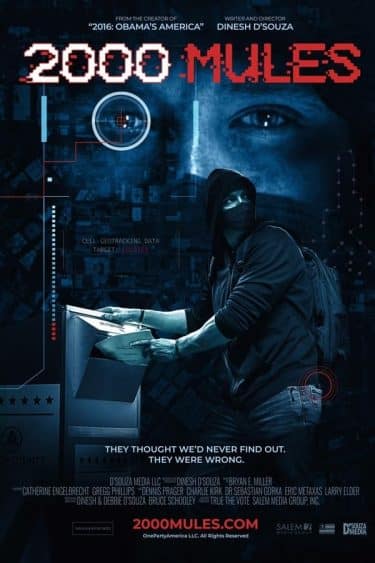

Instead, anti-abortionists concentrate on abortions that take place after the foetus has begun to resemble a very tiny (about 1 inch/2.5cm long) humanoid around 10 – 12 weeks after fertilisation, which is the time by which most induced abortions are performed. Anti-abortion films such as ‘The Silent Scream’ argue that abortion is wrong not only because it is murder but also because it is cruel, since it involves dismembering living mini-Beethovens. This is often backed up by heart-warming reports that long before delivery, the foetus can respond to music as well as to pain.

The problem with this highly emotive argument is that pain that isn’t remembered isn’t really pain in the usual sense of the word. If that weren’t the case, we would presumably insist on delivering all babies under general anaesthesia or by Caesarian section, because being squeezed through the birth canal for several hours would be extremely painful. After all, it is such a tight fit that the bones of the foetal skull are often forced to overlap to make the head small enough to pass.

We would also surely insist that male circumcision soon after birth should be done under anaesthesia as well. Babies certainly scream during this procedure (I performed it several times without even local anaesthesia on new-born Australians when it was still fashionable), but they never remember it as adults, any more than they remember being born. Surgical patients under light anaesthesia also react visibly when the knife goes in or when their fractures are manipulated but unless the anaesthetic is far too light, they don’t remember it either. So, ‘Silent Scream’ is misleading.

One might expect that pro-choice exponents and the Family Planning movement would welcome the IUD argument but in practice, they too have kept quiet. Their reasons for silence are very similar to those of the pro-lifers but their motivation is very different. Many anti-abortionists are old-fashioned sexual moralists whose ideological ancestors fought similar battles against contraception and votes for women a few generations ago. As well as those who feel genuinely offended by what they see as the murder of tiny babies with not-so-tiny souls, their ranks include many tedious male supremacists who fear giving women control over their own fertility and sexuality.

Obviously, the family-planning and pro-choice exponents are about as far away from that position as it is possible to be, but they fear that by mentioning the abortifacient effects of IUDs, they may deter some women and some family planning clinics from using a particularly efficient contraceptive method that is also very cost-effective. That is not hypocritical but it is dishonest. They also feared (until President Obama reversed American policy) the displeasure of the US government, which banned all financial aid to family-planning programmes that used, promoted or even discussed abortion. A US government-funded internet contraception library even prevented users from searching for articles containing the word ‘abortion’ until protests caused it to relent. Consequently, one of the strongest and most embarrassing arguments to use against anti-abortionists – that they are a bunch of odious hypocrites – is rarely deployed. I discussed my conclusions with a leading international figure in the world of population control and family planning. ‘You’re quite right, of course’ he said, ‘but you absolutely must not quote me’.

Even in Britain, family planning organisations deliberately conceal the physiological truth. I contacted the Family Planning Association, whose website stated very clearly that IUDs do not cause abortions. They said they could not give me a statement, even though in addition to gynaecologists, they employ many doctors who specialise in family planning and have diplomas to prove it. Instead, they referred me to the Faculty of Family Planning of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists – who could not help me either because I was not a member of the Faculty. In desperation, I sought the advice of Prof. John Studd, an old friend and, until his death in 2022, a very prominent and experienced gynaecologist. He said I could quote him and this is what he emailed me.

After further telephone discussions with “experts”, it seems there has been very little new research on this subject and the thinking is that it is a deliberate neglect in order not to offend the fundamentalists of Rome.

Nothing has changed since I wrote in 1976, for World Medicine:

People working in contraception have told me how there seems to have been almost a tacit international agreement not to discuss the abortifacient properties of the IUD. It is, they say, a useful birth control agent for many countries where an ignorant and unsophisticated peasantry is in thrall to religious leaders who accept contraception but not abortion and who could easily torpedo an IUD programme. I can understand their motives but I do not believe this is an attitude that should commend itself to a reasonably educated democracy.

Brewer C. Mortal Coils. World Medicine. June 2nd 1976, 33-6

I did manage to get a response from one leading British authority on contraception, who happens to be an Evangelical Christian, though he preferred not to be named. He is not an anti-abortionist but he relied on much the same ‘implantation’ argument that the anti-abortionist Prof. McLaren had used, though he also noted the large amount of ‘normal’ foetal wastage between fertilisation and implantation, even without IUDs. How likely was it, he asked rhetorically, that (I paraphrase) an omnipotent, omniscient and omnipresent God with the additional attribute of “omni-common sense”, would expect us to give the status, importance and respect to this unimplanted entity that it acquires, in his view, at the moment of implantation?

Surely it is now safe for the IUD to come out of the closet? The inconvenient truth has been published in scientific journals for over 40 years and even a Republican US government could not easily pretend that it neither knew nor cared about it. I think it would not now dare to withdraw funding from IUD programmes, especially in countries where its advantages make it a preferred method of contraception.

Surely not even Donald Trump really believes that the lot of poor women and their families would be improved by being forced to bear more children than they can support in countries where the process of childbirth is often still lethally dangerous? Properly presented, I think the IUD argument can breach the moral defences of the anti-abortionists (and the anti-stem-cell and anti-embryo research lobbies) more effectively than any other. Their leaders, including Pope John-Paul II, knew perfectly well that millions of IUD-induced early abortions were taking place every year but they mostly preferred not to acknowledge them and said nothing that compared with their regular torrents of outrage about abortions only slightly later in pregnancy. Where does that leave their moral credibility and authority?