In the seventh month of the lunar calendar, an unusual harmony descends upon Singapore’s public housing heartlands. Burnt offerings for the dead, food for the good brothers (hungry ghost) and puppet shows for an invisible audience. Meanwhile, in the same neighbourhood, a Malay family avoids cutting their nails at night, while a Christian teenager shrugs off the Hungry Ghost Festival entirely. No one argues. No one corrects. Everyone, it seems, simply coexists.

There is something fascinating within the Singaporean culture, made up of people from vastly different background and beliefs. From the outside looking in, it almost seems impossible for us to reconcile our differences. Elsewhere in the world, conflicts abound due to differences in beliefs, race or cultures – weirdly enough, not so much in Singapore. Despite the limited space, Singaporeans of all stripes share facilities with very little conflict or complaint. It might seem like Singaporeans co-exist through an unspoken agreement of tolerance and understanding, but I’d argue that there’s something more subtle and perhaps more powerful at play: “Kiasuism”.

Kiasu in a literal sense, is loosely translated to “fear of losing out” in Hokkien. More precisely, “an obsession to optimise every transaction and get ahead of others… driven by a constant apprehension of securing one’s share from a limited resource.” For example, back in 2019, If you happened to walk past a McDonald’s at midnight, you would find a long, snaking queue. It wasn’t for a midnight snack, but a queue for a Hello Kitty toy that launches at 7am the next morning. If you walk into a food court and see a pack of tissues on the table, with no one else there? It is a sign that the table is essentially reserved by someone afraid of not being able to find another seat later.

And what happens when Singaporeans are faced with superstitions that don’t align with their own beliefs? They default to being kiasu: avoidance of fuss over something trivial, to avoid risking the bad luck, however improbable that may be.

Among the many kiasu Singaporeans is my dear friend Joshua, 27, a Christian. During the Hungry Ghost Festival, as a mark of respect, many of us will walk around the food offerings that are a common sight on the floor… but there are times when a lack of concentration leads to a misplaced foot. That was the case for Joshua: “It’s kind of funny but also a little scary, when I accidentally step on a joss stick (during the Hungry Ghost Festival)”, he told me, “I’ll immediately apologise. Even if no one’s around. I don’t care if it sounds ridiculous, I just don’t want to be followed home by anything from the other side. It’s one of those ‘better safe than sorry’ moments for me.”

Across Singapore’s major ethnic groups, money gifting is also a common tradition, often seen at weddings, festive celebrations and funerals. While it is a shared tradition, the rules differ across the various cultures. For the Muslim community, during Hari Raya, green envelopes of duit Raya are handed to children as gesture of goodwill that reflect the Islamic values of zakat. The exact amount isn’t the point, instead, it’s the spirit of giving that matters. Then there is the Indian custom of wedding gifts. Cash offerings that end in 1 symbolise continuity, growth and an unbroken future. Whereas even numbers like those ending in 0 are seen as an end.

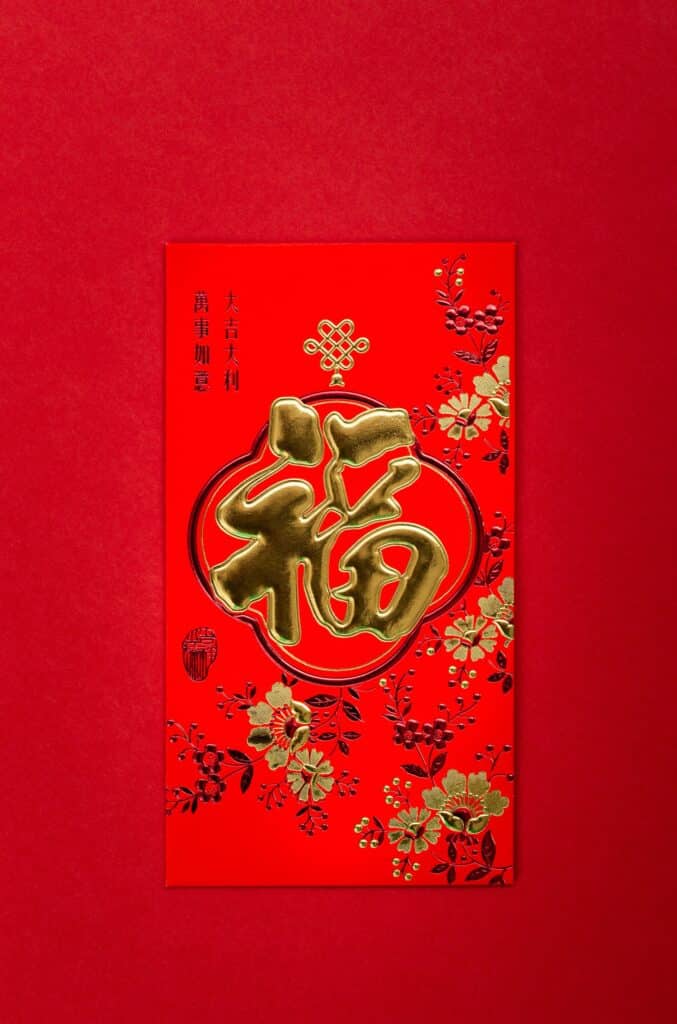

Meanwhile, on Chinese New Year, hongbao (red packets) are handed out to children, and unmarried adults (and sometimes to employees or married adults as a gesture of goodwill). The ones preparing the hongbao are very particular about the amount: even numbers, especially ending in 8, are considered lucky… except for 4. Do not under any circumstances hand over a hongbaocontaining $4. It’s a major taboo because it sounds the same as “死”, which means death in Mandarin. Odd numbers have their uses too; guests will prepare “baijin” for the families of the deceased during a Chinese funeral as a sign of respect and goodwill.

Confused? So are many Singaporeans. Online forums in Singapore are filled with questions as to whether $88 is okay at an Indian wedding, or what should they do if they stepped on offerings for the hungry ghosts. These aren’t just cultural questions, they are kiasu questions about how not to get it wrong. Kiasuism plays a huge part in the Singaporean culture where we fear not just losing out, but also fear offending, misstepping or appearing disrespectful.

Kiasuism has always been associated by the media with competitive queuing, discounts hoarding or worrying about neighbours outperforming you but, at its heart, it’s truly about avoiding negative outcomes – even ones that are highly improbable. The “better safe than sorry” attitude adopted by Joshua and many Singaporeans perfectly encapsulates kiasuism. Furthermore, it teaches empathy through caution. The fear of getting it wrong makes us attentive to the needs of others. In an environment unfamiliar to us, we quietly observe, check repeatedly, or follow the crowd, rather than risk doing something inappropriate. In a multicultural society, this cautiousness is not a weakness; it allows us to navigate through tricky waters, to behave and participate in situation that is unfamiliar to us.

Rather than challenging the superstitions that stem from beliefs in the supernatural or religion, many Singaporeans research them, ask discreetly, or simply follow along – not to conform, but out of respect for the others’ belief. That said, that does not mean in any way that Singaporeans do not question or challenge difficult topics. As Joshua noted when confronted with differing beliefs, “I’d probably just laugh it off and try to find a middle ground. I’m not the type to get caught in a ‘my belief vs yours’ battle. Respect goes a long way.”

Superstitions or beliefs rooted in the supernatural or religion are, by nature, intangible. It can be fruitless to get into a heated argument over something that cannot be proven, and doing so risks damaging relationships over something neither party can resolve. Different people hold different beliefs – and that’s okay. In a multicultural society like Singapore, there’s wisdom in knowing when to let things be. Often, the respectful silence, the small accommodations, and the willingness to give others space to believe what they believe – that’s what keeps the peace. And perhaps that, too, is a form of quiet wisdom that Singaporeans have long embraced.

Kiasu might be the driving force behind Singaporean’s competitiveness. As a country, Singapore is tiny, and has very limited resources. The result is a society trying to survive by out-thinking and out-preparing. Take education for example: Singaporean parents often engage in kiasu behaviours to ensure that their child do not fall behind in the highly competitive academic environment. This include preparing early childhood education, extra-curricular lessons, and multiple tuition classes. From the student’s point of view, they will inherit the pressure from their parents to perform. To outperform their peers and to prevent others from perceiving any incompetency. Even with these pressures, a study from the School of Social Sciences in Singapore Management University found that kiasu can translate into positive learning behaviours.

That, however, isn’t to say that kiasuism is without its downsides. Like any trait, when taken to the extreme, it can become counterproductive. The same fear that drives meticulous preparation can also turn into paralysis. This rings true when the pressure to succeed stifles risk-taking. What began as parents supporting their children in a highly competitive academic environment can quickly spiral into a relentless chase to meet self-imposed standards, disconnected from the child’s own interests. In the process, the child might miss out on pursuing their passion, leaving no room for their own creativity and individuality.

It can also breed distrust and quiet rivalry. With everyone hyper-focused on getting ahead, relationships may become transactional. People may be together simply because of mutual benefits and not genuine connections, which may become harder to forge. And when applied to cultural or religious practices, excessive kiasuism can result in performative respect: observing rituals not out of understanding and respect, but to avoid offending. The intention may be to maintain social harmony, but the sincerity is lost when the participation becomes mechanical.

Nevertheless, even in its performative state, the act of observing superstitions and other beliefs still seems to serve a valuable function in Singapore. The same goes for superstitions themselves. While they may lack scientific validity and often appear to be irrational – especially when you consider, for instance, that every morning during the Hungry Ghost Festival, cleaners clear the streets of burnt offerings and joss sticks without anything ever “following them home” – their significance lies elsewhere.

As Joshua told me, “I don’t really believe in most superstitions, but there’s one I grew up with: ‘finish your food or you’ll starve in your next life.’ It stuck with me, not because I fear the next life, but because it reminds me to appreciate what I have. So even though I’m not superstitious by nature, some of these sayings shape my habits in small but meaningful ways.” Joshua highlights how superstitions can have a positive and meaning impact in shaping someone’s behaviour, conveyed in a way that can carry over important lessons across generations.

Superstitions are fascinating. In a modern society like Singapore, known for its education standards, they remain an integral part of our culture. Could there be a better way to convey meaningful messages without relying on the supernatural? Certainly. But would that mean that superstitions disappear? I highly doubt it. The staying power of superstitions is due to the fact they tap into everyone’s primal fear. It makes people react irrationally. Superstitions don’t need to make sense; they just need to trigger a behavioural change. Whether it’s the fear of receiving a $4 hongbao during Chinese New Year, to attracting unwanted ‘friends’ from the other world, many of these beliefs stick because they invoke an emotion.

“Superstitions reflect deeper cultural values, history, and even emotional instincts”, Joshua told me, “So, while blind belief may be fading, respect for these traditions is still strong. It’s not about believing everything, it’s about knowing where it came from and why it matters. That balance is what makes Singapore’s diversity so special.”

And that, really, is the point: the goal is not blind faith. We’re still able to question where ideas come from, distinguish fact from fiction, and reflect on the actual lesson behind superstitions. If we can do that, they can be helpful cultural tools, rather than harmful limitations.

In the end, what makes Singapore’s multicultural harmony so enduring may not be merely tolerance or mutual understanding but a peculiar, deeply rooted instinct to avoid conflict, to stay safe, to get it right. Kiasuism, often caricatured as selfishness or over-competitiveness, reveals itself as something more tender: a cautious care, a quiet form of respect born from the fear of doing wrong by others. It’s not always graceful, and certainly not always perfect, but it works. Whether out of sincere belief or cautious observance, Singaporeans navigate their shared spaces with a unique kind of mindfulness. And perhaps in this fast-paced, hyper-rational world, a little fear of the unknown, and a little extra care not to step on someone else’s invisible line, is not a flaw, but a strength.

So next time you see someone sidestep a joss stick, hesitate before handing over a red package, or queue for hours for a little toy – perhaps don’t scoff. It is okay to be a little kiasu.