When we think about genetics, why do we almost automatically think about differences? We ask how different we are from other people because of our genes, and from other organisms. As a geneticist, I’ve always found it curious how we tend to focus on differences. Why not ask how similar we are? This was the topic of my talk at the Fronteiras do Pensamento Festival in May 2025, in Porto Alegre. I took the opportunity to talk about differences, similarities, races, genders… and jam jars (which will make sense in the end, I promise).

Some facts to ponder: we humans are approximately 99.9% identical in our genome. In the 0.1% that varies, we have a huge number of SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms); letters in the genome – called nucleotides; A, T, C or G – that can differ. SNPs don’t necessarily make a meaningful difference to the gene they’re in, but certain SNPs might show up more frequently in one population or geographic region, and with different frequencies in a different group. And it’s difficult to draw any conclusions from this.

We can say for example that, in a certain region of the African continent, a population has a SNP with a G in 60% of sequenced individuals. And perhaps this population also has a higher or lower frequency of heart disease. But we can’t say that this SNP is the cause of heart disease. It could just be coincidence. We don’t know what this SNP does; we only know that it’s there, at a frequency of 60%. This also doesn’t mean that it won’t exist in other populations, on other continents, at different frequencies.

The same SNP appears at 20% in a population from the European continent. If you have this SNP in your genome, we can calculate the probability that your ancestors came from this or that continent… but it will always be just a probability. We have to be wary of over-extrapolating from probabilities. Hypertension (high blood pressure) is more common in African-American men than in white Americans, but the frequency in men from sub-Saharan Africa is lower than in both. Single Americans are more likely to have heart disease than married men. I don’t imagine it’s a matter of genetic predisposition.

We also know that, within this 0.1% that varies from person to person, we find greater variation within certain populations than between different populations. Around 96% of this 0.1%. This means that if we randomly pick two people from the same region of the African continent, they will have more different genomes than a person from another part of the world. In other words, the differences that, historically and culturally, are used to define “race” – white, black, Asian, etc. – are 4% of 0.1%.

Genetics and race

We are all, from a biological perspective, much more similar than different. This is why genetics and anthropology societies consider human races to be social constructs, not biological ones. Races need to be studied and taken into consideration in public policies for social justice, because they have been a factor in discrimination and marginalisation. But they are not a biologically relevant concept.

To facilitate this understanding, let’s compare it to dog breeds. Does it make biological sense to talk about canine breeds? With significant genetic differences? Yes. The difference is stark: if in humans the genetic basis of so-called “racial” differences is 4% of the overall variation of 0.1%, in dogs the average genetic difference between breeds is approximately 27% of the overall variation (which is much smaller than the human variation).

In dogs, genetic differences are greater between breeds. Dogs of the same breed are absurdly similar to each other. The explanation for this is historical and commercial. Dogs were artificially selected. The artificial production of breeds led to a reduction in genetic diversity within each group. Imagine someone wanted small, white, furry, docile dogs to be companion animals. This breeder begins selecting from every litter those that most closely resemble these characteristics. And they cross them with each other, producing puppies that are increasingly whiter, smaller, furrier, and more docile. With each generation, genetic variation decreases, and the “purity” of the breed increases. Mutts, on the other hand, have a genetic diversity profile closer to that of humans. We are all mutts, and that’s a good thing.

Would it be possible to create human races the way we did for dogs? Yes, and some people have already tried (for example, Hitler’s obsession with the so-called “Aryan race”). But to do so, a process of “domestication” would be necessary, just as was done for animals and plants. This would reduce genetic diversity and increase susceptibility to and incidence of disease. This is already happening in various dog breeds. Many of them are more prone to deafness, skin diseases, hip and spinal problems, for example.

But what about differences in human appearance? Where do they come from? What do they mean? Let’s take the obvious: skin colour, which has historically been used as the primary marker of human “races.”

Evolutionarily, skin colour became associated with geography because of sunlight. The closer you are to the equator, with its higher amount of UV light, the more populations have darker skin tones, which offer greater protection. The farther you move from the equator, lighter skin becomes advantageous because it better utilises the limited UV light available at high latitudes to fix vitamin D.

There are several genes that code for skin colour and regulate the amount of melanin, which produces the enormous spectrum of colours we see in humans – because skin colour exists on a spectrum. Just look at makeup foundation charts. There are over 60 skin tones, from lightest to darkest. Children of the same parents can have different skin tones, depending on which genes they inherit from each parent. People with very similar skin tones, but from different regions of the planet, can have the same colour, but encoded by different genes. The same skin colour may not have the same genetic origin. Appearance does not define ancestry.

In dogs, the opposite occurs. Genes for coat type, for example, are the same across different breeds, and it’s easy to trace their origins because selection was entirely artificial. In other words, the genes that code for coat colour, ear shape etc., are generally known and have a common origin. We can easily trace the ancestry of dogs.

The same thing happens with other traits, for example lactose tolerance, which in adult humans is evolutionarily linked to dairy farming. The persistence of the ability to digest milk into adulthood emerged independently, and with other genes, in Europe, the Middle East, parts of Africa, and South Asia. In other words, there is no single “race” of lactose-tolerant people.

Genetics and gender

Let’s talk about gender differences. Are men and women more equal or more different? To answer that, I need you to open a jar of jam. And I’m sure that at some point in your life, you’ve either asked for help, or been asked for help, to open a jar of jam. And I’m also willing to bet that you’re a woman if you asked for help, and a man if you were asked for the job.

Why is opening windows generally easier for men than for women? Researcher Janet Hyde answered this question 20 years ago in a study published in 2005. She conducted a meta-analysis of studies on gender differences in abilities and behaviours, and classified the differences with a coefficient. The higher the coefficient, ranging from 0 to 2, the greater the difference. The closer to zero, the greater the similarity.

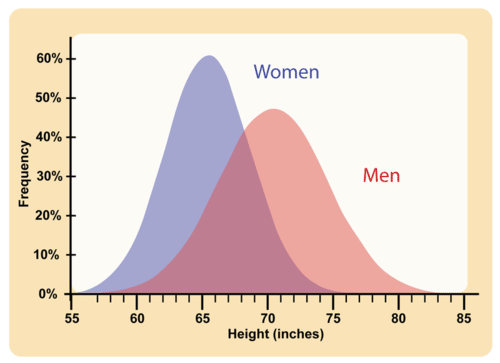

Some factors, like height, are obvious, with a coefficient around the maximum degree. In other words, if you randomly choose a man and a woman, it’s very likely that the man will be taller. Very likely, but not 100% certain.

The measured differences were classified into six categories: cognitive abilities, verbal and non-verbal communication, social or personality differences, measures of well-being such as self-esteem, motor differences such as throwing and strength, and general differences such as moral values.

Hyde found that the most significant differences were for throwing force, throwing speed, and grip strength. The latter is precisely the force needed to open a jar of jam. The coefficients of difference in sexual behaviours like masturbation and casual sex were also quite high. But then we wonder if there isn’t a strong cultural component here. Do women masturbate less because they think it’s wrong? Or do they prefer not to talk about it, even in opinion polls?

What didn’t make a significant difference was any of the “common sense” stuff. In total, 78% of the behaviours or skills studied had coefficients close to zero (30%) or less than 0.35 (48%).

Think about how many common-sense assertions about “essential” gender differences are part of our culture. We generally agree that men are better at geospatial location, women at languages. That women are more sensitive, men more rational, women more caring, and men better at maths. None of this has been statistically validated as significant. The degree of difference in behaviours like competitiveness was only around 0.07. Mathematical problem-solving ability: 0.08. Spatial orientation: 0.19 in one study, 0.13 in another, 0.44 in a third. Helping others was 0.13.

The belief that men and women have fundamentally different brains, programmed to be this way or that, is untenable. Of course, there are biological, evolutionary, and hormonal differences. But when it comes to specific abilities and skills, the truth is the same as for race: the difference is greater within gender than between genders. For example, there is more variation in mathematical skill levels among women, or among men, than there is when comparing men and women.

Furthermore, the brain is plastic. It’s not preprogrammed. We’re constantly learning new things, and these learnings are reflected in structural changes in the brain. The best example of this is the famous study of London taxi drivers. Until recently, becoming a taxi driver in London required passing a rigorous test (‘The Knowledge’). Candidates had to memorise the city map, know exactly which streets were one way, and how to take the quickest route between two points. They studied hard to obtain their licence.

The result? London taxi drivers had a brain region, the hippocampus, much more developed than non-taxi drivers in a control group. And the hippocampus became more developed according to the length of time they had worked as a taxi driver. So, do studies showing that men and women have different, more- or less-developed brain regions describe a purely biological phenomenon?

Only if we could track the brains of boys and girls from birth would we be able to identify cultural and social differences that shape behaviour and abilities – such as the amount of time we spend stimulating girls and boys with different types of toys, or the differences caused by varied tones of voice and facial expressions.

How this knowledge helps us

And why does all this matter? This is what I discuss with my students in the Evidence for Public Policy course at Columbia University. Knowing that biological races don’t exist can correct injustices that use these concepts to marginalise populations. At the same time, ignoring cultural and social factors can backfire, leaving discriminated populations without protection.

The same goes for gender. The insistence that men and women are more different than they actually are, and that this is immutable, is often used as an excuse to put women in their “rightful place.” It also serves to discourage girls and young adults from pursuing certain careers.

It can also lead to injustices in the professional world. A 2008 study conducted by Victoria Brescoll and Eric Luis Uhlmann of Yale University compared how volunteers reacted to a video simulating a job interview under identical conditions, changing only the interviewee’s gender. The videos showed the interviewee reacting angrily to a specific situation.

The volunteers rated the women worse in all situations, even though the videos were identical. Furthermore, they attributed the women’s behaviour to innate factors, with phrases like “she’s aggressive” and “she has no self-control.” For the men, aggressive behaviour was attributed to external stimuli: “He was angry,” “he was provoked.”

There are interesting ways to control these biases. One strategy that has been tested is using double-blind auditions for hiring. Orchestras that use this method have managed to increase the hiring of women from 5% in the 1970s to over 30% today. During the selection process, candidates play behind a screen. The judging committee cannot see the musician, it only listens and evaluates the performance.

It won’t be easy to change common sense. But we have to start somewhere. I started with my students. You can start with your family, your circle of friends. Remember the jam jar? It can be a great excuse to start a conversation: “Did you know something funny, that grip strength to open a jar is one of the few significant differences between men and women?”