I was looking on social media for videos about sustainable fashion and content discussing how to avoid cheaply made garments with short lifespans, and the value of opting instead for classic pieces that endure beyond trend cycles. I was then quickly funnelled towards videos of women telling me how to dress modestly and classically, emulating the look of classic, Gatsby-esque ‘old money’. I’m not ashamed to admit I let them draw me in a bit. Very attractive people strolling around European cities in well-fitting, muted shades has a real aspirational charm.

It got me thinking about changes I’ve made to my own wardrobe. I noticed that I’ve been favouring more neutral colours and thinking about my clothes in terms of timelessness. I couldn’t help but wonder if I’d been a victim of the same value system without realising, perhaps subtly guided by the same predatory algorithm into believing that what my summer wardrobe really needed was a smart shirt, implying it’s somehow inherently better than, say, a T-shirt.

The Old Money trend has had a considerably longer life cycle than other styles precisely because it feels aspirational in a time of economic uncertainty. In such periods, minimalism feels safer, less risky. Experimentation with personal style becomes less common as people try to present the most palatable version of themselves to avoid social or professional rejection.

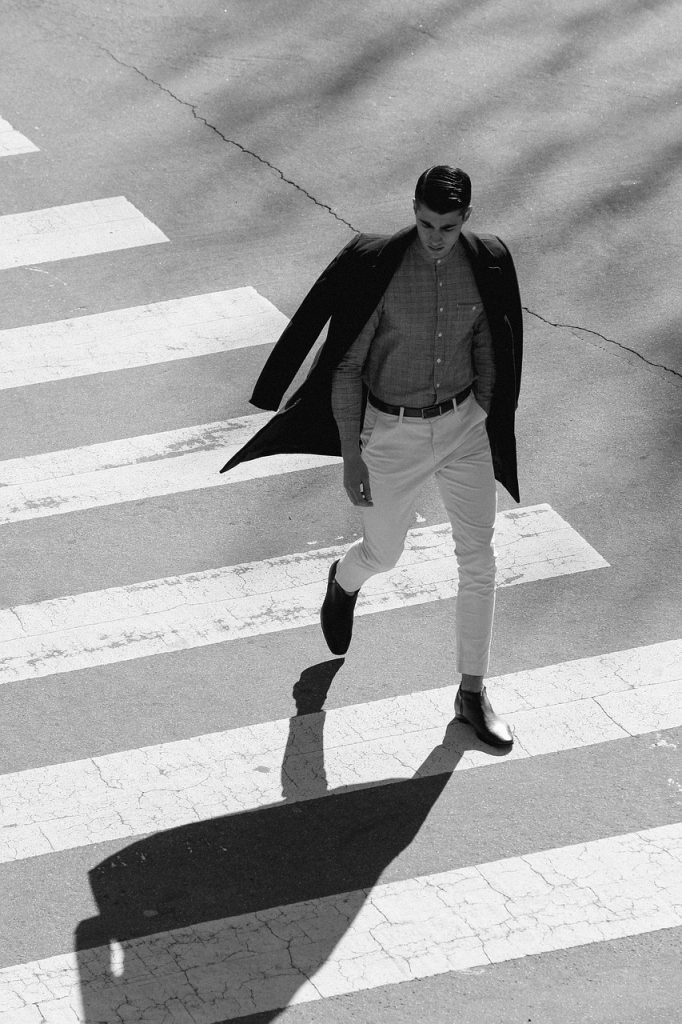

The old money aesthetic draws on the style associated with generational wealth, reflecting an understated, elite look. Typical features include tailored garments such as blazers, trousers, and trench coats; neutral, classic colour palettes like navy, black, beige, and grey; luxury fabrics like cashmere, wool, silk, and linen; and subtle logos, or none at all. In a similar vein, I also found videos promoting Quiet Luxury pieces, promoting minimalism, refinement, and the subtle signalling of wealth through quality and design.

Conservatism thrives on the belief that answers lie in the past rather than the future; on nostalgia, and how the trends we follow in clothing reflect broader cultural values. While I’m not suggesting that choosing to dress up and favouring a quiet luxury style makes one inherently conservative, embracing traditional aesthetics can be one step on the ladder. These styles are conservative by definition: they aim to preserve an idealised past that may never have existed.

It would be easy to say I’m overthinking a fashion trend, but what is more conservative than aspiring to traditionalism? Reflecting critically on how trends shape us is essential to being aware of their influence.

Absorbing conservative messaging

Although these videos appear designed to a conservative aesthetic and agenda, I discovered them while researching sustainability practices. This shows that different viewpoints can independently reach similar conclusions about the value of timeless clothing — something worth recognising and understanding.

The feeling that I might have been inadvertently absorbing conservative messaging left me feeling quite disjointed. After sitting with the feeling I realised the significant difference, even when the outcomes appear the same, between avoiding cheaply and unethically produced items and fearing the appearance of something looking cheap. For conservatives promoting the old money style, it doesn’t matter whether something is expensive or sustainably produced, as long as it appears elegant, understated, or expensive, at least from a distance or in a short clip.

Without close inspection, the two can appear almost identical, making it easy to slip from ethical concerns about clothing into the belief that modern styles are inherently cheap, unsophisticated, or brash.

The predatory aspect here is something that I kept coming up against after engaging with the old money aesthetic videos. At a time when economic mobility is increasingly out of reach for most young people, cosplaying wealth has become more and more popular. That is what so much of this aesthetic feels like to me, a yearning for a lifestyle that no longer exists in the same way, or at least for the aspirations once attached to it: home ownership, being the sole breadwinner, having ample disposable time. These now feel incredibly out of reach in our economy, because we live in a late capitalist nightmare where almost everyone has to work a lot harder.

Other trends that romanticise the past, like the trad wife movement, also sell a version of time that people associate with stability or a life of leisure. And the thing is, it works; it is appealing in those ways, but only if you squint and don’t think about it too hard.

And in myself, in the current climate, I’ve been experiencing anxiety about the future – as I think we all have, especially young people. I turned twenty-two last week, and I’m worried about my job and property-ownership prospects, along with most in my cohort. But it is those exact anxieties that they are preying on, trying to lead us into the mindset that ‘the old ways are the best’. But dressing like the fifth Roy sibling from Succession won’t make you a homeowner or exempt you from work, and it’s predatory for these conservative creators to try and sell you on that idea. It’s likely pushing people down the alt-right pipeline.

The rise of Cringe

All these preferences rely on having a direct opposite, an implied enemy, which I would say is the appearance of doing ‘too much’ or ‘trying too hard’. I have seen the term ‘cringe’ crop up time and time again in videos promoting classic, timeless fashion. It’s usually used in the context of comparing “cringe” versus “classy”, contrasting the supposed second-hand embarrassment or disgust you feel when looking at modern styles like baggy clothes, streetwear, punk-type looks, or dressed-down styles, with the relaxed, timeless, secure feeling of ‘high-class’ tailoring.

‘Cringe’ as an adjective has risen in popularity over the last ten years, and I would confidently classify it as a conservative trait, reinforcing conservative beliefs that ‘less is more’. The behaviours or individuals that frequently get called cringe online tend to be people considered different, those putting themselves out there, trying something new in an unconventional manner. Cringe culture, as it exists online, is at its core the mockery of the unconventional, and what is more conservative than that? Calling things cringe may not seem harmful, but it reflects and stokes an attitude that dislikes change, innovation, experimentation, and creativity.

Ultimately, conservatives’ only real joke about liberals has people with blue hair in the punchline. Said supposed joke usually also includes adjacent jabs about piercings, tattoos, eyeliner, etc. Underneath that well-flogged dead horse is the disgust they feel toward people freely expressing themselves beyond the mould. There is a belief of many conservatives, I’ve found, that they are the blueprint. I mean, many say they are the silent majority, and any innovation or growth is unnatural and transgressive.

As well as a rejection of what is over-the-top, there is also a rejection of what is different. But also, classism is baked into every aspect of this preservationist mindset, with a tendency to look down on those who cannot afford to dress more sophisticatedly. Another inherent, antithetical villain of quiet luxury is being seen as cheap.

A lot of modern conservatism, more so in the US, is focused on building personal wealth and centring one’s close family unit. There is something very individualistic, or if benevolent, done within a very narrow scope. This, I feel, ties into that – the idealisation and the aspiring to the landed gentry levels of generational wealth that it takes to truly carry off the old money look requires a fixated level of ambition and truly buying into the idea of entrepreneurship and personal growth, pursued within the capitalist system rather than against it.

That’s again very conservative, aiming to win the predatory game of chance rather than improving it to be fairer. The fear of looking cheap, also baked into this style, is then not looking like you’ve earned that money, like you were born at the top rather than working your way up.

What you will also see in all content surrounding the old money aesthetic, like the “clean girl” before it, is only thin, able-bodied and conventionally attractive white people. As with nearly everything else promoted and embraced by young conservatives, exclusion is essential to the look. The prominence of these figures in this aspirational trend reflects an idealised, exclusionary past, echoing the logic of white supremacist ideologies that promote a purified and homogeneous vision of society. This is ultimately where this was all leading; this trend is all the other things I’ve discussed, but at the end of the day, it really is just a stand-in for white supremacy.

Aesthetic conservatism is linked with political conservatism, particularly through the lens of “nostalgia politics”. The old money look being pushed on social media subtly reinforces traditional hierarchies tied to race, class, and gender. This becomes particularly visible when such aesthetics are used to mock or devalue contemporary styles associated with marginalised groups, such as streetwear, queer fashion, or alternative subcultures, being branded as “cringe” or “low status”.

Framing the old money aesthetic as a cultural soft-power tool for conservative values is therefore not an exaggeration. The end goal, I feel, is yet another method of exclusionary and classist recruitment tactics by the right, targeted primarily at fashion-conscious young people anxious about their future while trying to discover their identity through clothing.